Mark Kolsen

In 1891, Robert Green Ingersoll wrote that “If there is an abused word in our language, it is ‘spirituality.’” Today his words seem even more true. At least a quarter of all Americans identify themselves as “spiritual,” but what that means is hardly clear. Sociologists studying the phenomenon allow people to define the term any way they please; the result is that distinctions between terms such as spiritual, religious, sacred, divine, natural or supernatural collapse, rendering them almost meaningless. And in their published works, sociologists seem hesitant to probe how people distinguish their “spirituality” from “religiousness” or belief in the supernatural.

Then there are the “experts” on spirituality, who are increasingly treating spirituality as a human need. Consider Minnesota’s Bakken Center for Spirituality and Healing and the Canadian Virtual Hospice. The latter agency’s definition of spirituality closely resembles Bakken’s, which defines spirituality as “a sense of connection to something bigger than ourselves, and … involves a search for meaning in life.” Without offering evidence, these agencies claim this research is, according to the Bakken Center, “a universal human experience—something that touches us all.” As for when humans search for meaning, nurses Ruth Beckmann Murray and Judith Proctor Zente believe that search “comes into focus when [a] person faces emotional stress, physical illness or death.” Given that most humans experience emotional stress every day, it seems that the search for meaning is a human constant. But can this really be true among the 780 million of the world’s impoverished who struggle to find their next meal? Or for those working long hours at their jobs?

The medical community—or the new age movement—is not unique in viewing spirituality as a human need. In an April 2021 letter to the New York Times, secular philosopher Nancy Ellen Abrams wrote of spirituality as a human “need” and equated it with the “inspiration and shared motivation to survive.” She stated that a “spiritual perspective” is acquired by understanding “the astonishing place of intelligent beings like us in an evolving cosmos of dark matter and dark energy.” This “large perspective” offers humanity “the meaning of our moment in global history and the scale of our own reverberations into the future.”

However, how Abrams’ “spiritual perspective” differs from a scientific perspective—as well as how this perspective inspires and motivates people to survive—is unclear. True, as Steven Weinberg has written, understanding the universe “lifts human life a little above the level of farce, and gives it some of the grace of tragedy.” But—as Weinberg also wrote—the more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it seems pointless.” That pointlessness, especially our understanding of the universe’s fate, doesn’t seem very inspiring or motivating.

Among “experts,” there is also significant disagreement about the “bigger something” for which spiritual people search. Murray and Zente think this “something” is “harmony with the universe”—whatever that means—while Dr. Christina Puchalski, Director of the George Washington Institute for Spirituality and Health, says spirituality seeks “connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature and to the significant or sacred.” Hmmm … is this incredibly abstract definition suggesting that when hungry vegans gather for meals at vegetarian restaurants it is a spiritual experience?

More explicitly, Dr. Maya Spencer, at Britain’s Royal Society of Psychiatrists, thinks that the “something” for which spiritualists search is “cosmic or divine in nature,” i.e., a context beyond “everyday existence at the level of biological needs that drive selfishness and aggression. It means knowing that we are a significant part of a purposeful unfolding of Life in our universe.”

Her view is echoed by Mario Beauregard and Denyse O’Leary, authors of The Spiritual Brain, who define spirituality as “any experience that is thought to bring the experiencer into contact with the divine.” The authors make clear this “contact with the divine” is not just “any experience that feels meaningful.” Both these theistic-sounding definitions differ greatly from the Asheville, North Carolina-based team of New Agers at powerofpositivity.com, who offer “10 simple ways to add to your spirituality.” In addition to “helping others” and “giving love to yourself and others,” these ways include paying attention to your breathing, drinking a lot of water, or exercising and walking (barefoot) outdoors; in other words, by attending to some of your emotional and biological needs. This website seems in tune with the non-theistic views of millennials who identify as “spiritual but not religious.” Queen’s university PhD candidate Galen Watts interviewed thirty three of these millennials, and concluded that to millennials, the term spiritual signals (1) “that there is more to the world … than the mere material,” (2) that by attending to their mental and emotional states, they hope to gain “a certain kind of self knowledge” and (3) that they value “being compassionate, empathetic and open-hearted.” No mention here of the divine. On the other hand, the nature of the non-material “more” sought by millennials is never specified.

Amid the panoply of watery definitions, it’s tempting to eschew definitions and simply conclude, as Psychology Today does, that today, “Spirituality means different things to different people.” Or, in the words of the Bakken Center, to conclude that “Spirituality is a broad concept with room for many perspectives.” Or one might try, as Wikipedia valiantly does, to offer a definition that encompasses all definitions. Unfortunately, Wikipedia’s sixty-plus-word definition includes undefined terms such as sacred and inner dimension and dubiously equates supernatural with “beyond the known and observable realm.” (Students of quantum mechanics would argue that many particles predicted by mathematics are now “beyond the known and observable realm” but that these particles have nothing to do with the supernatural.)

Yet I would argue that spiritual needs a clear definition, especially its distinction from supernatural and religious. In fact, it’s a vital distinction, given that religion—as Richard Dawkind wrote in The God Delusion—is “very, very dangerous.” The danger extends beyond the social ills such as child abuse identified by Phil Zuckerman as endemic to religious communities. Religion has often guided decision making in powerful figures such as George W. Bush who, claiming inspiration from God, made the fatal decision to invade Iraq. Bush was no anomaly; as the BBC reported, “religion and war have gone hand in hand for a long time.” Or consider India’s Tirath Singh Rawat, who sanctioned the world’s largest religious festival (Hindus’ Kumbh Mela) during a global pandemic by saying “we are sure the faith in God will overcome the fear of the virus.”

That superspreading event undoubtedly contributed to thousands of deaths. As the world addresses serious problems such as COVID-19, poverty, inequality, climate change and weapons of mass destructions, populations need to understand what policy makers mean when they call themselves “religious” or “spiritual”. And to effect their policies, the powerful need to understand the spirituality or religiosity of their populations and how those views might affect their social, political and economic behaviours.

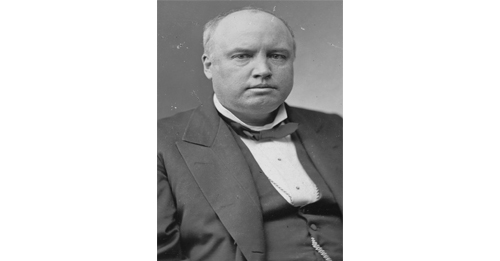

Interestingly, Robert Green Ingersoll offers us a solution. This is no accident. Ingersoll lived during the heyday of modern spiritualism, whose beginnings historians often trace to 1848, when two sisters Maggie and Katie Fox, claimed they could communicate with spirits through rappings and knockings. After American and European newspapers reported their claims, “spiritualism” became a widespread phenomenon, and many other “mediums” also gained fame through their alleged ability to communicate with the dead. Ingersoll himself attended several of these seances, and reporters often asked what he thought about them. He usually replied that the evidence presented by various mediums was ambiguous and unconvincing; in one case he called it “spurious”.

When he could not offer an explanation for phenomena he had witnessed. Ingersoll would point out, “If I should witness phenomena that I could not explain, I would leave the phenomena unexplained. … Why should I believe that [the medium] had the assistance of spirits? All I have a right to say is that I know nothing about how he does them.”

In 1896, he also refused to say that all mediums were imposters, especially regarding their claims to converse with the living, saying, “because I do not know” and “of the truth of these claims I have no sufficient evidence.”

On the other hand, Ingersoll always made clear that, lacking evidence, he did not “believe that these mediums get any information or help from ‘spirits’.” He also once stated that mistake, emotion, nervousness, hysteria, dreams, love of the wonderful, dishonesty, ignorance, grief and the longing for immortality—the desire to meet the loved and lost, the horror of endless death—account for these phenomena. People often mistake their dreams for realities. … The real and unreal mix and mingle until the impossible becomes common and the natural absurd.

In 1896, he told the New York Journal that spiritualism was “a religion,” and that like every other religion, “I do not know that any medium has added to the useful knowledge of the world. … [They] have told us nothing about astronomy, geology, or history, have made no discoveries, no inventions and have enriched no art.”

Yet Ingersoll also expressed a much more sympathetic attitude toward spiritualism than secularists might express today. In contrast to traditional Christians, spiritualists were, he said, not bigoted, did not believe in salvation by faith, and did not preach the consolation of hell or conceive of God as an “infinite monster”. Spiritualists did not expect “to be happy in another world because Christ was good in this;” nor were “their hands and feet tied with passages of scripture.”

Unlike Christians, they do not persecute their neighbours.” in fact, Ingersoll believed that spiritualists “have done good.” They “believe in intellectual hospitality” and ask people “to investigate and then to make up their minds from the evidence.” Unlike Christians, “The spiritualists of today have witnesses, which is something.” he thought they also enjoyed themselves and believed in “having a little pleasure in this world. They are social, cheerful and good natured.” Finally, like Ingersoll, nineteenth century spiritualists had “little confidence in the spiritualism of eighteen hundred years ago.”

To be continued in the next issue….

Lead:

Religion has often guided decision making in powerful figures such as George W. Bush who, claiming inspiration from God, made the fatal decision to invade Iraq. Bush was no anomaly; as the BBC reported, “religion and war have gone hand in hand for a long time.” Or consider India’s Tirath Singh Rawat, who sanctioned the world’s largest religious festival (Hindus’ Kumbh Mela) during a global pandemic by saying “we are sure the faith in God will overcome the fear of the virus.”