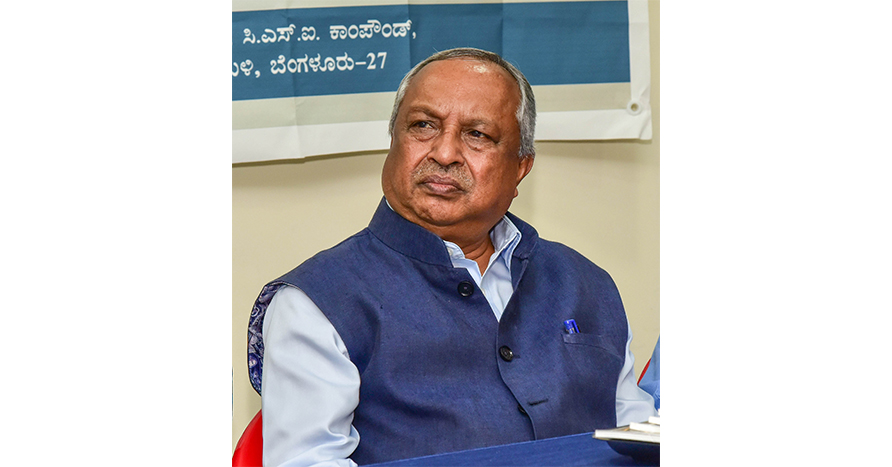

– Badri Narayan

Social historian, Author of ‘Republic of Hindutva’

Noted social historian Badri Narayan has written extensively on Dalits and saffron politics. In his latest book, Republic of Hindutva, he explains how the RSS is constantly reinventing itself to spread its worldview. Sunday Times talks to him about its role during elections, and how the Opposition can change tack to counter this challenge Interviewed by Avijit Ghosh

You describe RSS as the ‘garbhagriha’ of Hindutva politics. You also say that “the political forces attacking the RSS are in fact attacking its shadow but are unable to understand the real RSS.” What, according to you, is the new RSS?

Post-90s India was reshaped by liberalisation and globalisation. These produced new forms of social aspirations. The RSS needed to respond to all these complexities and they did. It is changing itself constantly, redefining its meaning and arguments in the context of emerging new social challenges. Their positioning on issues like environment and transgenders etc shows how the organisation has responded effectively to the questions raised by aggressive modernity and rapid globalisation. It is working to appropriate its opposites by selective forgetting, contextual remembrance and reinvention of traditions, memories and histories. Recently RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat explained the need to selectively forget some ideas of Bunch of Thoughts, a collection of speeches of M S Golwalkar, because according to him ideas change when society and time change. But it is also true that on the ground, RSS is struggling to counter the image caused by actions of fringe elements who claim to be representing Hindutva.

RSS has been working to accommodate varied social groups — Dalits and tribals — into the larger Hindutva fold for years. Can you give us some grassroot examples of how the organisation works these days?

RSS works with mostly invisible and the most marginal Dalits, nomadic-semi-nomadic, ex-nomadic and tribal communities in three ways. One, through sewa projects such as establishing schools, hospitals, and reviving traditional water resources to carve out space in the hearts and mind of the marginal communities. Two, by reinterpreting their heroes, histories, icons and other identity resources and making them part of the grand Hindutva identity. Three, by responding to the evolving urge of creating religious space and visibility for marginal communities.

For instance, smaller Dalit communities in Bundelkhand such as kabootaras, kuchbadhiyas, Hari and saperas aspire for a temple of their community deities in their bastis. We observed during our fieldwork how saperas wanted to invite Yogi Aditya Nath to inaugurate a temple of their snake deity. They have the desire but not the capacity to build temples. RSS responds to these desires by helping them build local temples of their deities which become identity markers for them. Also Sangh forms network with katha mandlis, pravachankars, Ramleelas troupes, all popular among marginal communities in remote areas, to forge linkages with them. Through these popular and religio-folk methods, Sangh evolves a Hindutva cultural common sense among them. Left-centrist, mainstream Ambedkarite discourses fail to see this new turn of emerging identity aspiration among Dalits and tribals. Ambedkar realised this urge and incorporated it in his schemes of political actions but after sometime even Ambedkarite discourses could not pay attention to such inherent urges of the communities.

How does the RSS look at and relate to B R Ambedkar today?

Interestingly, the Sangh is working to transform the image of Ambedkar from social critic to mahapurush, something like a deity for not only Dalits but for all section of Indians. They recreate Ambedkar’s image in a way, so that no political or social group can use him to create any kind of anti-Hindutva narrative. Whenever someone mentions Ambedkar’s criticism of caste system, they appreciate this criticism and sometime claim themselves the position of a social reform agency which is working to remove all these evils of Indian society.

RSS claims to be a cultural organisation. Yet it was actively involved in the 2014 and 2019 national polls. What exactly is its role during elections?

Sangh influences the functioning of BJP, directly or indirectly. Some Sangh pracharaks work for BJP in various capacities. At many places, Sangh works as an agency to collect feedback, remove dissatisfaction among BJP cadres which emerges during elections due to various reasons. At many places, it plans booth management and brings voters to the booths. In 2014, a section of local RSS cadres worked in various parts of Uttar Pradesh to collect people’s responses after a Modi lecture. During 2019, we observed that they persuaded undecided chaiwalas,vegetable vendors, daily wagers to vote for BJP.

In your view, what can Opposition parties do to counter the hegemonic influence that the RSS seeks to build?

Opposition parties need to understand that any counter hegemony may be created by debates and dialogues between competing groups, and for that they need to revise drastically their understanding about Sangh. In production of any hegemony and counter hegemony, culture and diction of political language plays an important role. The old diction of Opposition politics such as secularism needs to be rethought and reinvented in the context of rapid growth of Hindutva social bhava (collective feeling) within a bigger section of communities.

Source: ‘The Times of India’