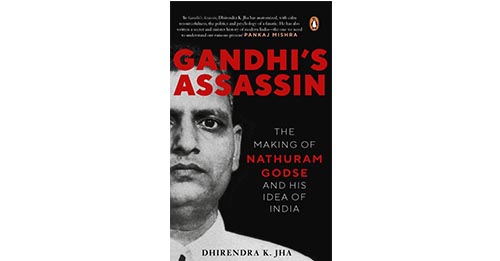

‘Gandhi’s Assassin: The Making of

Nathuram Godse and His Idea of India’

by Dhirendra K. Jha

Pages: 288

Penguin

Price Rs. 540/-

– Md. Zeeshan Ahmad

From previous issue…..

In the early twentieth century, the rising demand of political representation in legislative bodies, with the mass nationalism gathering steam, elicited some constitutional concessions from the colonial government. Prominent among them were the 1919 and 1935 Acts, which expanded the base of franchise, which hitherto had remained the sole preserve of the urban community. This socio-political churning, owing to which the urban commercial and professional class was becoming politically less relevant, however, was simultaneously taking place along with the non-Brahman movement in few of the provinces in British India.

This particular development can be best understood by looking at the tumultuous politics of Bombay province, which was the home province of Savarkar. On the Brahmin and non-Brahmin conflict, former diplomat T.C.A. Raghavan, in an essay, observes that, in Maharashtra, “The threat to the urban based Brahmin from the rich peasantry of Kunbi Maratha castes [who have also entered legislature], the attack upon Hindus in Punjab, and the Moplah rebellion in Malabar all seemed to have a common cause – weakness and disunity among Hindus.”

To contain this caste conflict, Raghavan notes, “Savarkar tried to give a cultural definition to the word Hindu to stress the common racial history of all Hindu.” For his project, Savarkar conceptualised two tools – Hindutva and Sangathhan. The former, as Raghavan notes, would unify the Brahmin and non-Brahmin as being of the same cultural background, and also attempted to increase the unity of Hindus against Muslims. While, though later, “removing the caste differences and prejudices would complete the task that Hindutva began.”

After experimenting with this model of politics in the laboratory of Bombay province, Savarkar thought of trying it at the pan-India level. After his internment ended in 1937, and upon becoming the President of the Hindu Mahasabha, Savarkar started canvassing the philosophy of Hindutva, that too with a missionary zeal.

To the chagrin of Savarkar, the Indian National Congress, the principal vehicle of the nationalist movement, with leaders like Gandhi and J.L. Nehru at its forefront, didn’t just dismiss the idea of Hindutva, but even explained to the masses how diabolical this idea was is in their fight against the colonial power. By virtue of the Congress being a pan-India party, representing all castes and communities, secularism and democracy formed its backbone. Therefore, there was no place for sectarianism in Gandhi’s scheme of things.

This development, however, didn’t just frustrate Savarkar to the core, but as Jha observes, thereafter “much of Savarkar’s life would be defined by his antipathy towards Gandhi”.

Consequently, Savarkar started bashing everything for which Gandhi stood, prominent among them being, Hindu-Muslim unity and non-violence. According to Savarkar, by resorting to these tools, Gandhi was fooling and making Hindus weak. Gandhi even came be identified by the Savarkarities as a Muslim sympathiser. With the passage of time, Savarkar’s antipathy got metamorphosed into hatred against Gandhi, as his model of politics was fast losing its relevance.

The Savarkar-Gandhi conflict is best summed by Jha in the following words, “For a section of Chitpawan Brahmins [both Savarkar and Godse came from this caste], particularly those who couldn’t reconcile with the gap between their traditionally privileged position and their actual status in the contemporary socio-political setting, anxiety was a permanent emotion of the time. As they longed to redeem their lost glory, the charisma of Gandhi didn’t appeal to them.”

Before one forgets, it also needs to be recalled that the idea of Hindus and Muslims constituting two nations was first given by Savarkar. Later, the All-India Muslim League, with M.A. Jinnah at the driving seat, exploited this divisive idea to its hilt by playing with the anxieties of the Muslim elite. So, both Hindu and Muslims communalist political parties were feeding each other. Needless to mention, this regressive politics was collectively frustrating the cause of the national movement.

When Godse meets Savarkar, and thereafter …

Godse met Savarkar for the first time when he was nineteen years old in 1929 at Ratnagiri, where the latter was serving his internment post his release from Cellular Jail. As mentioned earlier, Godse’s father was in the postal service, so he was frequently transferred, and the last transfer brought him to the coastal town of Ratnagiri in Bombay province. By late 1920, Savarkar has established himself as a proponent of Hindutva, and at least in Bombay province, and especially among Chitpawan Brahmins, he had gained unparalleled popularity.

Therefore, so mesmerized was Godse with Savarkar, and his domineering personality, about whose revolutionary activities he had heard while growing up, that in no time the latter became his alter ego.

Later, Godse became close to Savarkar, particularly after 1938, when he joined the Hindu Mahasabha, with Savarkar at its President. It is to be noted here that Godse joined the Hindu Mahasabha without severing his bond with the RSS. For political purposes, Godse even used to travel frequently with Savarkar to distant places.

Savarkar and Godse didn’t just share the strict relationship that usually is witnessed between any normal member of an organisation and its President. It was much more than that. Savarkar gave a loan to Godse for opening a newspaper named Agrani, of which Godse was the editor. This paper mainly published outrageous articles fomenting hatred against Muslims, or criticising Gandhi’s policies. Many a times, because of such articles, the newspaper was censured, and even fined.

to be continued…