A LETTER TO C.RAJAGOPALACHARI by KARUMUTTU THIYAGARAJAN CHETTIYAR iN 1939

Madurai

1st May 1939

To

The Hon’ble Sree C.Rajagopalachariar

Prime Minister of the Government of Madras Madras

Dear Sir,

May I introduce myself as an old loyal Congressman who though without publicity, has worked and sacrificed not a little. To mention only a few instances, which occurred after I withdrew from the political field in 1921, to take to industry – when officials of Madura came to The Sree Meenakshi Mills Ltd., which is under my management, in 1929 after Gandhiji’s Dande March, to distribute pamphlets among the labourers of our Mills, – prompted by patriotism, and pride that Gandhiji first wore his loin cloth as my guest I made bold to say that no facilities would be afforded the Government to carry on counter propaganda against a great national movement inside our Mills. Mr. J F Hall, ICS., then Collector of Madura with a threat of imprisonment under the Arms Act for not despositing my revolver in time in the absence of renewal of licence, took a letter of undertaking from me that I should dissociate myself from the Congress and refrain from financing it. Again when Sir R.K.Shanmugam, kt., the President of the Assembly wrote to me in 1934 to support his candidature, I curtly replied to the illustrious Justicite that I could not do so owing to my sympathies with the Congress. As I had two votes, there was great pressure from all quarters. I disobeyed the “order” of the late Mr.E.M.Viwanathan Chettiar who held 1/16 share of the Company and was besides financing the mills to the extent of five lakhs. Next an “injunction” from Dewan Bahadur A.M.Murugappa Chettiar then a Director of the Mills, and Sir P T Rajan, the Development Minister, to cast at least the vote of the Company in favour of Sir Shanmugam, met the same fate. Your esteemed colleague, Dr.Subbaroyan was present on the latter occasion. My sufferings for such little things were greater than even courting imprisonment. Mr.N.M.R.Subbaraman will speak to the part I played, silently, in the last general election to support the Congress. These unhappy incidents I have the unpleasant task of recounting if I am to merit you sympathy as a staunch Congressite. In the sincere hope that you may, therefore, have some consideration for the words of a true Congressman, and that you as Prime Minister, will be open-minded, sympathetic and conciliatory, I approach you in a friendly spirit to write about the burning topic of the day in our Presidency.

I have read carefully all that has been said for and against compulsory Hindi. I am still unconvinced by the arguments advanced in favour of it. When the matter has been discussed for the last fifteen months in the Press and on the platform at the expense of a great deal of eloquence and energy in arguing the pros and cons of compulsory Hindi, it may indeed seem to be superfluous to raise the point again here. However, as the matter is so important, kindly permit me to touch it, presenting a view with no bias against the well-meant measure.

In the first place if Hindi had been made an optional subject there would have been no opposition against it, at least on the part of unprejudiced intelligentsia. What has given a momentum to the widespread agitation is that the language was made compulsory. Therefore, we shall first examine this preliminary issue.

It is always right to make a good thing compulsory? True. we do want primary education to be made compulsory. This is already a hard and laudable task that the Congress intends to undertake. This does not, therefore, need to be made harder still, by compelling the study of Hindi in the secondary school, among the children of a generation, which is hostile to it. Even when primary education has not yet been made compulsory in this poor miserable land, where 96% cannot speak their thoughts fairly in their own mother tongue, can an alien language be made compulsory in a scondary school?

When one is put under compulsion to do a thing, he looks upon it with suspicion, and Hindi, though a widely spoken dialect of great India, will forfeit the natural love that it might otherwise engender.

If and when a need arises for a thing it will certainly overcome all obstacles and will secure and hold its own. Why then force it prematurely? Secondly, Hindi has been made compulsory to bring solidarity between the provinces. Has it achieved this desired good effect? No! It has, on the other hand, produced a misunderstanding between us and our beloved North Indian brethren, who are suspected to have a design to dominate over us, and, what is worse, it has created a split in our own province itself. It has unfortunately revived communal feelings that were fast receding into the background. We have offered our opponent a first class political issue to fight us and are thereby making them great heroes. Are we not responsible for this? But for this unfortunate step they would have rested in peace. Having now given them new life to fight, we have had to make use of much-condemned weapon, the Criminal Law Amendment Act, as a defence against them. To correct one error, one is apt to fall into greater. Mistake follows mistake, which adds strength to the opposition. It would be another mistake belittle or underrate the movement. If it had not strength we need not have had recourse to the Criminal Law Amendment Act, bitterly condemned by us. the use of this violent Act is a logical proof of the strength of the movement. Hindi – Urdu controversy has also taken a communal turn. Bengal, Punjab and other provinces may add to this commotion when they are faced with this controversy.

Has language always united people? Are not the Hindus of the South and the North speaking different languages more united that the Hindus and Mohammedans of the North speaking one language. Religion has more influence to unite people. But we cannot think of a national religion. One’s mother-tongue is as dear as mother. Interference with language or religion may only lead to disruption. Repression we have seen, can only delay a people’s triumph.

Coming to the merits of the question, has India the common characteristics of a distinct nation, for us to think of a national language? India is a little continent, embracing different races and communities. Europe without Russia is about as large as India, and yet does not boast of one language – great as it is, it does not derive it greatness from one language. Canada, South Africa and Switzerland each uses different languages, and yet each is united itself, nor does history shows that the solidarity of any nation or empire grew out of oneness of language? The British Empire, too, embraces a great medley of languages, which have not for centuries broken its unity. All the provinces and states too, have not come to an agreement on this important point. And the change of all the provinces and states coming to an agreement is yet very slight and remote. The Congress also has come to no conclusion on this point and has given us no mandate. Yet in the province, there is much ado about this, mixing up politics with education, and adding to our complications, when there is no urgent need for it.

Even when federated India decides upon Hindi as the language of the Central Government, still there will be no need to make Hindi compulsory in the secondary schools in all provinces. It can then be introduced as an optional subject in the college. It can be specialised in two years during arts course or any other special course in Politics, Journalism etc., Just as French and classical languages are studied as a second language for higher studies. There would be no opposition to the study of Hindi as an optional subject in the college classes. The leaders will learn Hindi out of necessity.

The study of an alien language in secondary schools will do no good. It will only be a waste of time, unless it is pursued during the college course and also afterwards put in practice.

It is vainly argued that in England, Latin and Greek are taught compulsorily and that they have not spoiled the English language. It is not correct to say that they are compulsory subjects in England now. And there is no parallelism between these ancient dead languages with their marvellously rich literature, and Hindi, which scarcely has any literature at all. The suggestion of a comparison between the two would give offence to a classical scholar. It would be like comparing an eagle and a poor crow. Latin and Greek are closely allied to English and they are taught in order to enrich it. Greek and Latin are also read to unearth and to enjoy the hidden treasures buried in those ancient rich classical literature. Hindi is not a language allied to Tamil and it is also not a classical language like Greek or Latin or Sanskrit that can enrich our Tamil with its literature.

Whether Hindustani or Hindi is sought to be made the national language is not clear as yet, for Hindustani is differential from Hindi. The worst part of it is that Hindi has no script of its own and we have yet to decide on this point, which bristles with difficulties. Besides, when a language is learnt in different scripts it will soon turn into different dialects that will not be easily understood. A uniform pronunciation in speech will require a practical knowledge of phonetics. Again, Hindi, it is authoritatively stated, has already several dialects, and none of them has yet been cultivated.

A word about the explanation that Hindi will not endanger our rich language and its great culture. Has not English, that has spread very little, done irreparable harm to Tamil? Do we not write and speak in English even in our own homes? Have we not thought that if we did not speak in English it would be below our dignity? Has not English education broken through our customs and culture? Are we not shining in borrowed feather? Where would we have been, if our great leader, Gandhiji, had not redeemed us and made us return to our own ancient culture and learning? And yet, can we, in fairness, say that the learning of Hindi will not interfere with Tamil and its culture? It is needless to dilate upon ancient Tamil and its unique culture as they are not disputed.

On the one hand, we want a national language to make this continent of great india into one nation, and on the other hand, we also want to divide the existing provinces into smaller one on a linguist basis. Is this not inconsistent? Can we not at least postpone controversial questions such as that of a national language, until we have made India a real nation? Then it will be time to think of the universal language.

At first, it was said that Hindi would be the lingua franca of India. But a mixed jargon can never become a state language. Gandhiji now prefers to say that Hindi would be a Rashtrabasha of India. The leaders have not yet placed all their (linguistic) cards on the table. As the Congress is against secret diplomacy they should soon tell the public in detail what position they want Hindustani to occupy under Congress rule.

Article XIX (a) of the Congress Constitution only says that the proceedings of the Congress and its committees that shall ordinarily be in Hindustani and (b) that the proceedings of the Provincial Congress Committee shall ordinarily be in the language of the Province. This in itself is clear and allowable. And if the Congress Election Manifesto has only stated that Hindi would be made a compulsory subject, the voters, in their great enthusiasm for Swaraj, might not have noticed or even minded the consequences of such ‘gifts’, and it would have then stood the Congress Ministry in good stead, to introduce this measure as approved by the people. It would have relieved the Ministry of this very important constitutional issue, as the electorate would not now say that the Ministry has no mandate from them to make Hindi a compulsory study. But instead of this frank avowal, which would have gained by truthfulness and sincerity, the Manifesto openly and emphatically declared that the Congress would not interfere with religion or language.

No foreign language, however good or elastic, can ever become the language of hundreds of millions speaking some hundreds of languages or dialects and perhaps not sprung from the samestock. The fruit sought from oneness of language cannot be gathered till all these hundreds of languages or dialects offer a victim at the altar of Hindi. For the sake of an uncertain, if not utopian ideal, shall we run the risk of prizing so little the rich inheritance of language bequeathed to us by our venerable ancestors, that we are prepared to make a sacrifice, even the least, of that certain ancient pledge on behalf of a would be national Hindi. Hindi, in any event, is an alien language to Tamilians, and should never be made the subject of compulsory study.

It is said that English is compulsory in schools and colleges, and that no objection is taken to it. English schools and colleges were started by the British Government, Missionaries and other philanthropists to satisfy the need felt by the people to learn the King’s English to take service under a foreign Government. Others learnt it for business. English is a highly cultivated language, made international. It affords every facility, and urges all nations to learn it out of necessity. We wanted Swaraj in order to be masters of our own affairs and to retain the culture of our languages, and not again to have to use a language like Hindi, which is as foreign to us as English. We do not want to substitute one foreign language for another, even if Indian. For we want Poorna Swaraj, for our Province also, without own culture in our languages.

True, students have recently passed a resolution in their Conference in Madras favouring the study of Hindi as a compulsory subject. They are said to be the future citizens of India. Hence it is argued plausibly that it should be taught compulsorily. If it is a wise measure to consult the young generation that will make the citizens of tomorrow, on this political question, for a similar reason, we might consult their inexperience and romantic tendencies on other political questions as well, and take their answers as our decisions in the conduct of Government. So too, since students, now have caught the infection of strike, we shall also commend strikes, and do away with all laws that are not acceptable to immature minds! Would this be sound wisdom or logic?

One more point and this letter is concluded. Our educational system is very defective. Existing curricula are so heavy that they paralyse the energy of the students and make too many of them unfit for any useful purpose after they leave the schools and colleges. They cannot even earn their living. Their illiterate brothers fare far better in this respect. It will be cruel to add to the syllabus and burden of our children with an additional language that will not help them either temporally or spiritually. The worthy object of the Congress Government to adopt the mother tongue as medium of instruction is unhappily less appreciated that it deserves, precisely because it is obscured by the controversy about Hindi.

Million are starving. This issue and other important one are shelved. We are accused by those in distress of fiddling while Rome is burning.

It is indeed unfortunate that the popular Ministry, so early in its life, should be forced into this unpleasant controversy. Language is so sacred that dallying with it will have fatal consequences. Should we not end this internal strife before the gulf is too widened? Can we afford to have fresh quarrels within when we have greater battles to face without?

The intensity of my love of Tamil make me hope sincerely that this letter, coming as it does from a lover of the country, may effect what hundreds of resolutions passed at public meetings have failed to do.

If you are pleased to discuss the matter personally, I shall be glad to wait on you. If the interview converts me to your opinion I shall certainly bear your message to Tamil Nadu.

As you are an esteem countryman of mine, I have ventured thus far to address you with frankness which kindly excuse in one who, though familiar, means to be respectful.

With an apology for being so insistent in my earnest appeal to you I conclude, resting on my unbounded love for my mother tongue and my mother country, and feeling confident in your happy possession of the power and the goodness needed for generosity to end this unhappy episode by a stroke of the pen.

I remain,

Yours truly

Karumuttu Thiagarajan

Courtesy : Co-Chamber Journal – June 2016 of

ICCI, Coimbatore

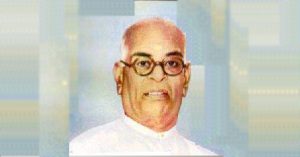

KARUMUTTU THIYAGARAJAN CHETTIYAR

Karumuttu Thiagarajan Chettiar (1893-1974) was industrialist cum businessman, born in Tamil Nadu. He got educated in Sri Lanka, where he edited a newspaper championing the cause of the plantation workers. He returned from Sri Lanka and was elected Secretary of the Madras Province Congress Committee of the Indian National Congress. Thanthai Periyar and Karumuttu attended AICC meeting together. He took an active part in the struggle for Indian Independence. He founded 14 textile mills, 19 educational institutions, the Bank of Madura and the Madurai Insurance Company etc.

Karumuttu Thiagarajan started the registered office of his industry at 251-A, West Masi Street, Madurai and Mahatma Gandhi wore loin cloth there on 22nd September 1921. He was an ardent lover of architecture, music and literature. His affection to Tamil language was special. He published a newspaper in Tamil and named it Tamil Nadu. He hoisted the flag at the anti-Hindi Conference at Trichy in 1938. He hosted Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose during 1940. His torch is being carried by his Son Karumuthu Thiagarajan Kannan.

The Modern Rationalist brings out the letter of Karumuttu Thiagarajan Chettiar addressed to C.Rajagopalachari, the then Prime Minister of the Government of Madras in 1939, in which he discusses the probable ill effects, if learning Hindi language is made compulsory in the Madras Presidency. Besides he analyses the language problem, likely to arise in independent India and emphasises that there is no need to have one language as ‘National’ in a continent-country like India which embraces different races and communities. He concludes India does not derive its greatness with boast of one language.