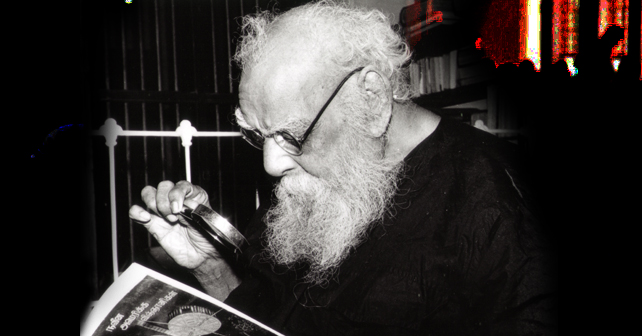

A.R.Venkatachalapathy Historian,currently working on a biography of periyar

For those in contemporary India who agonise over the place of electoral politics in their quest for reform and justice – Irom Sharmila, Anna Hazare or Aruna Roy, for example – the career of the great Tamil reformer Periyar (1879-1973) holds many lessons.

Periyar E.V. Ramasamy – whose 138th birth anniversary falls on Saturday – is credited with democratising Tamil society. Yet, he was a leader who disavowed electoral politics in his long and influential career. From the time of the Non-Cooperation Movement (1919) until his death in December 1973, Periyar and the parties he was allied with or led never contested elections.

In the early 1920s, as the Swarajists were desperately trying to turn the Congress towards entry into the new legislature introduced under the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms, Periyar sided with the No-Changers who opposed it. Paradoxically though, Periyar’s exit from the Congress, in November 1925, was due to failure of his repeated attempts to make the Congress accept caste-based reservation in legislature.

Periyar’s political career was thus torn between the need to politically empower the lower castes and the deep suspicion he had about the corrupting power of the electoral process and holding office.

Those who wish to effect any [social] transformation cannot do so by political power. A few individuals may attain selfish gains through politics. They may indulge in political gambling. But they can do little for public good or for the real benefit of the people.

He therefore declared categorically, in the first years of independent India, that the ‘Dravidar Kazhagam does not enter legislatures. It does not try to form ministries. It does not contest elections.’

At the root of Periyar’s distrust of electoral politics was his experience of the wheeling-dealing of the Swarajists. Periyar condemned both the Minto-Morley and Montford reforms as leading to squabbles for the fishes and loaves of office. Periyar’s critique of the reforms was also grounded in his contention that the Congress was essentially a Brahminical organisation and that the fruits of nationalist agitation would be cornered by Brahmins.

But the larger reason behind his antipathy to elections was the radical social programme that he charted after leaving the Congress.

The cost of courting popularity

Periyar launched the Self-Respect movement, and by 1927, was attacking religion, god and scriptures. In a public talk at Chidambaram he stated that the presiding deity was only worth upending and being used as a washing stone, and compared idols to mortar and pestle stones. He also derided all rituals including marriage rituals. He also propounded a rationalist critique of religion and advocated atheism.

A similar radicalism informed his understanding of the women’s question as well. In a polemical book titled ‘Why were Women Enslaved?’ Periyar argued that marriage and motherhood, and the lack of property rights, lay at the root of women’s inferior status. Periyar also called for the burning of texts such as Ramayana. In 1956, he launched an agitation to burn the pictures of the god, Ram and the breaking of the idols of Pillaiyar (Ganesha). In 1971, at the age of 93, he organised a major conference in Salem where a procession of tableaux and dioramas depicted ‘obscene’ incidents from Hindu puranas. In short, his was not a programme that would court popularity. He therefore harboured no illusions about how he would fare in an election.

‘If someone like me develops the desire for office can I articulate the kind of issues and words that I now speak? Can anyone who seeks to capture political power speak in this manner? For e.g. I ask: ‘Can a stone be god? Can god eat food? Does god need a wife? Why conduct the annual ritual of marriage for gods? Who benefits from all these?’ Will the one who asks such questions get any votes? But if one does not ask questions in this manner will our foolish people understand a thing? Thus it is inevitable that one has to speak of superstitions in this manner. And this does indeed bear some result.’

This understanding came from Periyar’s own experience. In the 1930s, a nationalist paper taunted the Justice party, the non-Brahmin party that Periyar supported, asking if it agreed with Periyar’s policy of divorce and remarriage for both men and women. In an election meeting Periyar responded: If Draupadi could have five husbands and still desire one more, and if Dasaratha could have 60,000 wives and such people could be venerated ‘what calamity will befall if a woman, on the death of her husband marries another man?’ Immediately the chairman of the meeting interjected, saying that if one spoke like this the party would lose votes. The speaker after him regretted Periyar’s words on the same grounds.

The lesson was well learnt and if anything only confirmed Periyar’s views on riding the horses of politics and social activism.

As early as 1927, he had editorialised that, ‘To have a relationship between social work and political work will only result in great harm to social work. … Indulging in politics means that one cannot avoid becoming a scoundrel one day or the other, and betray nation and society. … Unless we take a pledge from those who want to work on a social agenda that they’ll not indulge in direct politics the social movement cannot function and succeed.’

Q : What is the most fraudulent term in the world?

A : Well, it’s democracy.

Q : But is it even more fraudulent than the word god?

A : Oh, oh, oh! God is a general fraud. Everybody gains a share from it. But the fraudulent

term democracy is not like that. Only cheats and scoundrels and their gangs can corner a share and gain benefit. Democracy is only livelihood for wastrels and frauds. What else can one say about Democratic Front; United Democratic Front; Progressive Democratic Front; Radical Democratic Front; Ultra Radical Democratic Front; Independent Democratic Front, Democratic Alliance, etc.

In such a situation even if Periyar and his party were to contest and win elections, the ‘result would not be any different’. Until the people advanced in the sphere of knowledge and experienced a change of heart, ‘whoever became a minister would only achieve personal gains and provide little benefit to the people.’

Periyar was, however, at pains to dispel the view that he was arguing for a restricted franchise for only the rich and the educated. ‘The only power that the working class and the poor have is the vote.’

Finding a way out

Periyar’s disengagement from contesting elections did not however mean a disavowal of the state. Even in the first Self Respect Conference (1929), when many radical resolutions were passed, he had stated: ‘In order to attain the objectives and implement the programme of the Self-Respect movement it is necessary to look to the government for assistance even as we seek the support of the people.’ This was especially so in relation to emancipatory social legislation regarding the abolition of disabilities rising from gender and caste, such as for instance bringing in laws to give property rights to women, etc.

What then was the way out? He saw the primary task of the Dravidar Kazhagam as working with the people to dispel their ignorance. Only then would the people realise their real needs and choose the right representatives. What was the movement to do until then? ‘What we need is a propagandist movement. Propagate, Propagate, Propagate so that people change’.

This did not mean that Periyar kept off election campaigns. There was no election in his lifetime that he did not actively take part in. He would offer to campaign, whether he was welcome or not, for a party or an alliance that would best implement aspects of his programme. It was always a hectic campaign and drew huge crowds. Except in the historic 1967 elections, the party that he supported always won. Periyar devised a strategy of providing broad support to the party in power and achieved incremental advance for his social agenda.

The success of this strategy is an inseparable part of modern Tamil Nadu’s political history.

‘To have a relationship between social work and political work will only result in great harm to social work. … Indulging in politics means that one cannot avoid becoming a scoundrel one day or the other, and betray nation and society. … Unless we take a pledge from those who want to work on a social agenda that they’ll not indulge in direct politics the social movement cannot function and succeed.’

– Periyar EVR (1927)