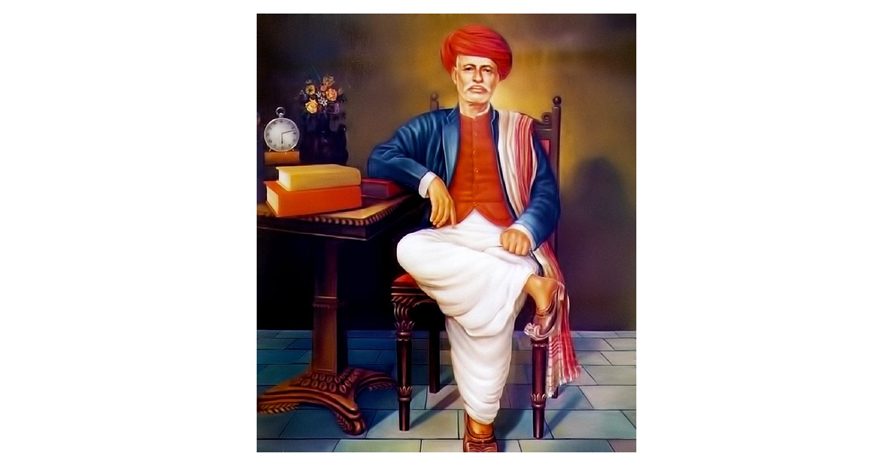

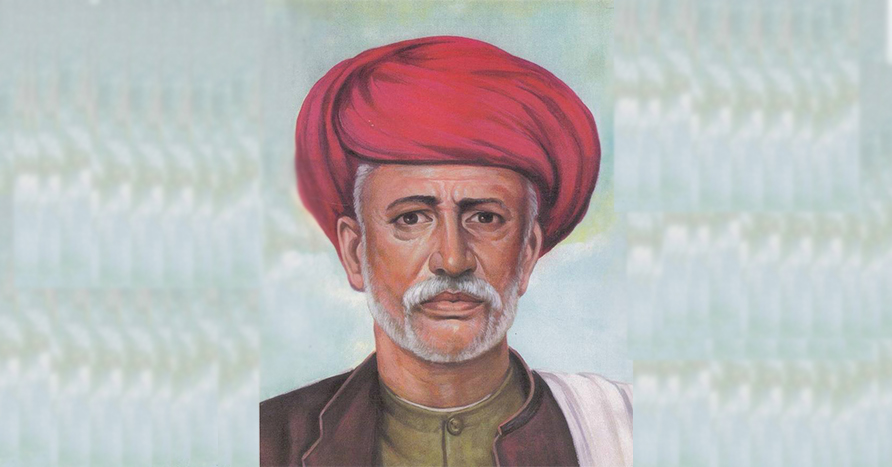

The following is the appeal made by Mahatma Jothiba Phule to the Government of British India on 19th October 1882 on the educational needs of the vast majority of the toiling masses of the land. Phule made this appeal as a merchant, a cultivator and as the Municipal Commissioner of Peth Joona Ganja, Maharashtra.

Almost all the ideas of Mahatma Jothiba Phule (1827 – 1890) and Thanthai Periyar E.V.Ramasamy (1879 – 1973) on the need of education to all and on the mission of remedies to the social maladies were on similar line despite the fact that they had not met each other and not even aware of the mission of the other. The brahminical dominance in the educational system and public services were well thought out and acted upon alike by both the social revolutionaries. Great men not only think alike but act alike too – Editor

My experience in educational matters is principally confined to Poona and the surrounding villages. About 25 years ago, the missionaries had established a female school at Poona but no indigenous school for girls existed at the time. I, therefore, was induced, about the year l851 to establish such a school, and in which I and my wife worked together for many years. After some time I placed this school under the management of a committee of educated natives. Under their auspices two more schools were opened in different parts of the town. A year after the institution of the female schools, I also established an indigenous mixed school for the lower classes, especially the Mahars and Mangs. Two more schools for these classes were subsequently added. Sir Erskine Perry, the president of the late Educational Board, and Mr. Lumsdain, the then Secretary to Government, visited the female schools and were much pleased with the movement set on foot, and presented me with a pair of shawls. I continued to work in them for nearly 9 to 10 years, but, owing to circumstances, which it is needless here to detail, I seceded from the work. These female schools still exist, having been made over by the committee to the Educational Department under the management of Mrs. Mitchell. A school for the lower classes, Mahars and Mangs, also exists at the present day, but not in a satisfactory condition. I have also been a teacher for some years in a mission female boarding school. My principal experience was gained in connection with these schools. I devoted some attention also to the primary education available in this Presidency and have had some opportunities of forming an opinion as to the system and personnel employed in the lower schools of the Educational Department. I wrote some years ago a Marathi pamphlet exposing the religious practices of the Brahmins, and, incidentally among other matters, adverted therein to the present system of education which, by providing ampler funds for higher education, tended to educate Brahmins and the higher classes only, and to leave the masses wallowing in ignorance and poverty. I summarized the views expressed in the book in an English preface attached thereto, portions of which I reproduce here so far as they relate to the present enquiry:—

‘Perhaps a part of the blame in bringing matters to this crisis may be justly laid to the credit of the Government. Whatever may have been their motives in providing ampler funds and greater facilities for higher education, and neglecting that of the masses, it will be acknowledged by all that injustice to the latter, this is not as it should be. It is an admitted fact that the greater portion of the revenues of the Indian Empire are derived from the ryot’s labour-from the sweat of his brow. The higher and richer classes contribute little or nothing to the state exchequer. A well-informed English writer states that our income is derived, not from surplus profits, but from capital; not from luxuries, but from the poorest necessaries. It is the product of sin and tears.

‘That Government should expend profusely a large portion of revenue thus raised, on the education of the higher classes, for it is these only who take advantage of it, is anything but just or equitable. Their object in patronizing this virtual high class education appears to be to prepare scholars who, it is thought would in time vend learning without money and without price. If we can inspire, say they, the love of knowledge in the minds of the superior classes, the result will be a higher standard, of morals in the cases of the individuals, a large amount of affection for the British Government, and unconquerable desire to spread among their own countrymen the intellectual blessings which they have received.

‘Regarding these objects of Government the writer above alluded to, states that we have never heard of philosophy more benevolent and more utopian. It is proposed by men who witness the wondrous changes brought about in the Western world, purely by the agency of popular knowledge, to redress the defects of the two hundred millions of India, by giving superior education to the superior classes and to them only. We ask the friends of Indian Universities to favour us with a single example of the truth of their theory from the instances which have already fallen within the scope of their experience. They have educated many children of wealthy men and have been the means of advancing very materially the worldly prospects of some of their pupils. But what contribution have these made to the great work of regenerating their fellowmen? How have they begun to act upon the masses? Have any of them formed classes at their own homes or elsewhere, for the instruction of their less fortunate or less wise countrymen? Or have they kept their knowledge to themselves, as a personal gift, not to be soiled by contact with the ignorant vulgar? Have they in anyway shown themselves anxious to advance the general interests and repay the philanthropy with patriotism? Upon what grounds is it asserted that the best way to advance the moral and intellectual welfare of the people is to raise the standard of instruction among the higher classes? A glorious argument this for aristocracy, were it only tenable. To show the growth of the national happiness, it would only be necessary to refer to the number of pupils at the colleges and the lists of academic degrees. Each wrangler would be accounted a national benefactor; and the existence of Deans and Proctors would be associated, like the game laws and the ten-pound franchise, with the best interests of the constitution.

‘One of the most glaring tendencies of Government system of high class education has been the virtual monopoly of all the higher offices under them by Brahmins. If the welfare of the Ryot is at heart, if it is the duty of Government to check a host of abuses, it behoves them to narrow this monopoly day by day so as to allow a sprinkling of the other castes to get into the public services. Perhaps some might be inclined to say that it is not feasible in the present state of education. Our only reply is that if Government looks a little less after higher education which is able to take care of itself and more towards the education of the masses there would be no difficulty in training up a body of men every way qualified and perhaps far better in morals and manners.

‘My object in writing the present volume is not only to tell my Shudra brethren how they have been duped by the Brahmins, but also to open the eyes of Government to that pernicious system of high-class education, which has hitherto been so persistently followed, and which statesmen like Sir George Campbell, the present Lieutenant Governor of Bengal with broad universal sympathies, are finding to be highly mischievous and pernicious to the interests of Government will ere long see error of their ways, trust less to writers or men who look through high-class spectacles, and take the glory into their own hands of emancipating my Shudra brethren from the trammels of bondage which the Brahmins have woven around them like the coils of a serpent. It is no less the duty of each of my Shudra brethren as have received any education, to place before Government the true state of their fellowmen and endeavour to the best of their power to emancipate themselves from Brahmin thralldom. Let there be schools for the Shudras in every village; but away with all Brahmin school-masters! The Shudras are the life and sinews of the country, and it is to them alone, and not to the Brahmins that Government must ever look to tide over their difficulties, financial as well as political. If the hearts and minds of the Shudras are made happy and contented, the British Government need have no fear for their loyalty in the future.’

Primary education

There is little doubt that primary education among the masses in this Presidency has been very much neglected. Although the number of primary schools now in existence is greater than those existing a few years ago, yet they are not commensurate to the requirements of the community. Government collect a special cess for educational purposes, and it is to be regretted that this fund is not spent for the purposes for which it is collected. Nearly nine-tenths of the villages in this Presidency, or nearly 10 lakhs of children, it is said are without any provision, whatever, for primary instruction. A good deal of their poverty, their want or self-reliance, their entire dependence upon the learned and intelligent classes, is attributable to this deplorable state of education among the peasantry.

Even in towns the Brahmins, the Purbhoos, the hereditary classes, who generally live by the occupation of pen, and the trading classes seek primary instruction. The cultivating and the other classes, as a rule, do not generally avail themselves of the same. A few of the latter class are found in primary and secondary schools, but owing to their poverty and other causes they do not continue long at school. As there are no special inducements for these to continue at school, they naturally leave off as soon as they find any menial or other occupation. In villages also most of the cultivating classes hold aloof, owing to extreme poverty, and also because they require their children to tend cattle and look after their fields. Besides an increase in the number of schools, special inducements in the shape of scholarships and half-yearly or annual prizes, to encourage them to send their children to school and thus create in them a taste for learning, is most essential. I think primary education of the masses should made compulsory up to a certain age, say at least 12 years. Muhammadans also hold aloof from these schools, as they some-how evince no liking for Marathi or English. There are a few Muhammadan primary schools where their own language is taught. The Mahars, Mangs, and other lower classes are practically excluded from all schools owing to caste prejudices, as they are not allowed to sit by the children of higher castes. Consequently special schools for these have been opened by Government. But these exist only in large towns. In the whole of Poona and for a population exceeding over 5,000 people, there is only one school, and in which the attendance is under 30 boys. This state of matters is not at all creditable to the educational authorities. Under the promise of the Queen’s Proclamation, I beg to urge that Mahars, Mangs, and other lower classes, where their number is large enough, should have separate schools for them, as they are not allowed to attend the other schools owing to caste prejudices.

In the present state of education, payment by results is not at all suitable for the promotion of education amongst a poor and ignorant people, as no taste has yet been created among them for education. I do not think any teacher would undertake to open schools on his own account among these people, as he would not be able to make a living by it. Government schools and special inducements, as noted above, are essential until such a taste is created among them.

(to be continued…)

Source : Selected Writings of Jotirao Phule