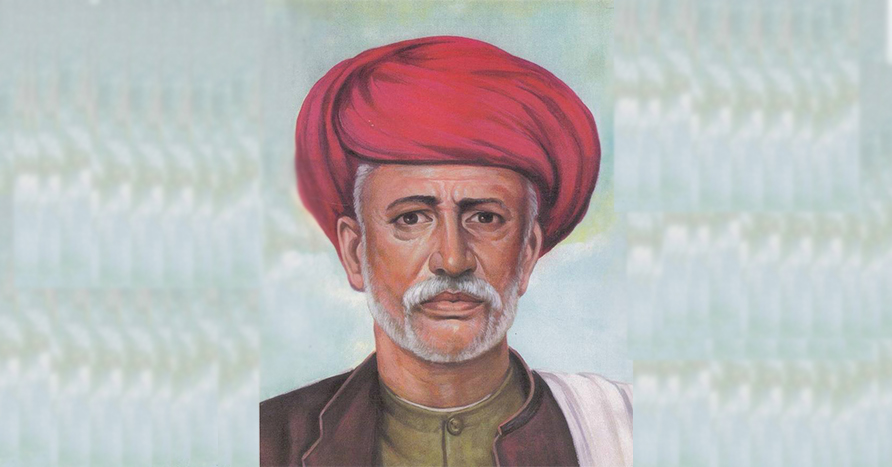

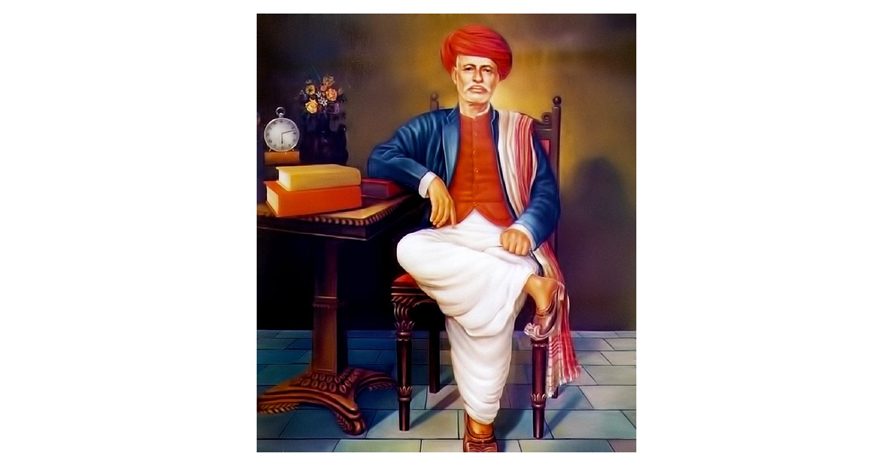

The following is the appeal made by Mahatma Jothiba Phule to the Government of British India on 19th October 1882 on the educational needs of the vast majority of the toiling masses of the land. Phule made this appeal as merchant and cultivator and as the Municipal Commissioner of Peth Joona Ganja, Maharashtra.

Almost all the thinking of Mahatma Jothiba Phule (1826 – 1890) and Thanthai Periyar E.V.Ramasamy (1879 – 1973) on the need of education to all and on the mission of remedies to the social maladies were on similar line despite the fact that they had not met each other and not even aware of the mission of the other. The brahminical dominance in the educational system and public services were well thought out and acted upon alike by both the social revolutionaries. Great men not only think alike but act alike too – Editor

… continuing from the previous issue

With regard to the few Government primary schools that exist in the Presidency, I beg to observe that the primary education imparted in them is not at all placed on a satisfactory or sound basis. The system is imperfect in so far as it does not prove practical and useful in the future career of the pupils. The system is capable of being developed up to the requirement of the community, if improvements that will result in its future usefulness be effected in it. Both the teaching machinery employed and the course of instruction now followed, require a thorough remodeling.

(a) The teachers now employed in the primary schools are almost all Brahmins; a few of them are from the normal training college, the rest being all untrained men. Their salaries are very low, seldom exceeding Rs.10, and their attainments also very meagre. But as a rule they are all unpractical men, and the boys who learn under them generally imbibe inactive habits and try to obtain service, to the avoidance of their hereditary or other hardy or independent professions. I think teachers for primary schools should be trained, as far as possible, out of the cultivating classes, who will be able to mix freely with them and understand their wants and wishes much better than a Brahmin teacher, who generally holds himself aloof under religious prejudices. These world, moreover, exercise a more beneficial influence over the masses than teachers of other classes, and who will not feel ashamed to hold the handle of a plough or the carpenter’s adze when required, and who will be able to mix themselves readily with the lower orders of society. The course of training for them ought to include, besides the ordinary subjects, an elementary knowledge of agriculture and sanitation. The untrained teachers should, except when thoroughly efficient, be replaced by efficient trained teachers. To secure a better class of teachers and to improve their position, better salaries should be given. Their salaries should not be less than Rs. 12 and in larger villages should be at least Rs.15 or 20. Associating them in the village polity as auditors of village accounts or registrars of deeds, or village postmasters or stamp vendors, would improve their status, and thus exert a beneficial influence over the people among whom they live. The schoolmasters of village schools who pass a large number of boys should also get some special allowance other than their pay, as an encouragement to them.

(b) The course of instruction should consist of reading, writing Modi, and Balbodh and accounts, and a rudimentary knowledge of general history, general geography, and grammar, also an elementary knowledge of agriculture and a few lessons on moral duties and sanitation. The studies in the village schools might be fewer than those in larger villages and towns, but not the less practical. In connection with lessons in agriculture, a small model farm, where practical instruction to the pupils can be given, would be a decided advantage and, if really efficiently managed, would be productive of the greatest good to the country. The text-books in use, both in the primary and Anglo vernacular schools, require revision and recasting as much as they are not practical or progressive in their scope. Lessons on technical education and morality, sanitation and agriculture, and some useful arts, should be interspersed among them in progressive series. The fees in the primary schools should be as 1 to 2 from the children of cess-payers and non-cess pavers.

(c) The supervising agency over these primary schools is also very defective and insufficient. The Deputy Inspector’s visit once a year can hardly be of any appreciable benefit. All these schools ought at least to be inspected quarterly if not oftener. I would also suggest the advisability of visiting these schools at other times and without any intimation being given. No reliance can be placed on the district or village officers owing to the multifarious duties devolving on them, as they seldom find time to visit them, and when they do, their examination is necessarily very superficial and imperfect. European Inspector’s supervision is also occasionally very desirable, as it will tend to exercise a very efficient control over the teachers generally.

(d) The number of primary schools should be increased—

(1) By utilizing such of the indigenous schools as shall be or are conducted by trained and certificated teachers, by giving them liberal grants-in-aid.

(2) By making over one half of the local cess fund for primary education alone.

(3) By compelling, under a statutory enactment, municipalities to maintain all the primary schools within their respective limits.

(4) By an adequate grant from the provincial or imperial funds.

Prizes arid scholarships to pupils, and capitation or other allowance to the teachers, as an encouragement, will tend to render these schools more efficient.

The Municipalities in large towns should be asked to contribute whole share of the expenses incurred on primary schools within the municipal areas. But in no case ought the management of the same to be entirely made over to them. They should be under the supervision of the Educational Department.

The municipalities should also give grants-in-aid to such secondary and private English schools as shall be conducted according to the rules of the Education Department, where their funds permit, such grants-in-aid being regulated by the number of boys passed every year. These contributions from municipal funds may be made compulsory by statutory enactment.

The administration of the funds for primary education should ordinarily be in the hands of the Director of Public Instruction.

But if educated and intelligent men are appointed on the local or district committees, these funds may be safely entrusted to them, under the guidance of the Collector, or the Director of Public Instruction. At present, the local boards consist of ignorant and uneducated men such as Patels, lnamdars, Surdars, etc., who would not be capable of exercising any intelligent control over the funds.

Indigenous schools

Indigenous schools exist a good deal in cities, towns, and some large villages, especially where there is a Brahmin population. From the latest reports of Public Instruction in this Presidency, it is found that there are 1.049 indigenous schools with about 27,694 pupils in them. They are conducted on the old village system. The boys are generally taught the multiplication table by heart, a little Modi writing and reading, and to recite a few religious pieces. The teachers, as a rule, are not capable of effecting any improvements, as they are not initiated in the art of teaching. The fees charged in these schools range from 2 to 8 annas. The teachers generally come from the dregs of Brahminical society. Their qualifications hardly go beyond reading and writing Marathi very indifferently, and casting accounts up to the rule of three or so. They set up as teachers as the last resource of getting a livelihood. Their failure or unfitness in other callings of life obliges them to open schools. No arrangements exist in the country to train up teachers for indigenous schools. The indigenous schools could not be turned to any good account, unless the present teachers are replaced by men from the training colleges and by those who pass the 6th standard in the vernaculars. The present teachers will willingly accept State aid, but money thus spent will be thrown away. I do not know any instance in which a grant-in-aid is paid to such a school. If it is being paid anywhere, it must be in very rare cases. In my opinion no grants-in-aid should be paid to such schools unless the master is a certificated one. But if certificated or competent teachers be found, grants-in-aid should be given and will be productive of great good.

Higher education

The cry over the whole country has been for some time past that Government have amply provided for higher education, whereas that of the masses has been neglected. To some extent this cry is justified, although the classes directly benefited by the higher education may not readily admit it. But for all this no well-wisher of his country would desire that Government should, at the present time, withdraw its aid from higher education. All that they would wish is, that as one class of the body politic has been neglected, its advancement should form as anxious a concern as that of the other. Education in India is still in its infancy. Any withdrawal of State aid from higher education cannot but be injurious to the spread of education generally.

A taste for education among the higher and wealth classes, such as the Brahmins and Purbhoos, especially those classes who live by the pen, has been created, and a gradual withdrawal of State aid may be possible so far as these classes are concerned; but in the middle and lower classes, among whom higher education has made no perceptible progress, such a withdrawal would be a great hardship. In the event of such withdrawal, boys will be obliged to have recourse to inefficient and sectarian schools, much against their wish, and the cause of education cannot but suffer. Nor could any part of such education be entrusted to private agency. For a long time to come the entire educational machinery, both ministerial and executive, must be in the hands of Government. Both the higher and primary education require all the fostering care and attention which Government can bestow on it.

The withdrawal of Government from schools or colleges would not only tend to check the spread of education, but would seriously endanger that spirit of neutrality which has all along been the aim of Government to foster, owing to the different nationalities and religious creeds prevalent in India. This withdrawal may, to a certain extent, create a spirit of self-reliance for local purposes in the higher and wealthy classes, but the cause of education would be so far injured that the spirit of self-reliance would take years to remedy that evil. Educated men of ability, who do not succeed in getting into public service, may be induced to open schools for higher education on being assured of liberal grants in aid. But no one would be ready to do so on his own account as a means of gaining a livelihood, and it is doubtful whether such private efforts could be permanent or stable, nor would they succeed half so well in their results. Private schools, such as those of Mr. Vishnu Shastree Chiploonkar and Mr. Bhavey, exist in Poona, and with adequate grants-in-aid may be rendered very efficient, but they can never supersede the necessity of the high school.

The missionary schools, although some of them are very efficiently conducted, do not succeed half so well in their results, nor do they attract half the number of students which the high school attract. The superiority of Government schools is mainly owing to the richly paid staff of teachers and professors which it is not possible for a private school to maintain.

The character of instruction given in the Government higher schools, is not at all practical, or such as is required for the necessities of ordinary life. It is only good to turn out so many clerks and schoolmasters. The Matriculation examination unduly engrosses the attention of the teachers and pupils, and the course of studies prescribed has no practical element in it, so as to fit the pupil for his future career in independent life. Although the number of students presenting for the Entrance examination is not at all large when the diffusion of knowledge in the country is taken into consideration, it looks large when the requirements of Government service are concerned. Were the education universal and within easy reach of all, the number would have been larger still, and it should be so, and I hope it will be so hereafter. The higher education should be so arranged as to be within easy reach of all, and the books on the subjects for Matriculation examination should be published in the Government Gazette, as is done in Madras and Bengal. Such a course will encourage private studies and secure larger diffusion of knowledge in the country. It is a boon to the people that the Bombay University recognizes private studies in the case of those presenting for the entrance examination. I hope, the University authorities will be pleased to extend the same boon to higher examinations. If private studies were recognized by the University in granting the degrees of B.A., M.A. etc., many young men will devote their time to private studies. Their doing so will still further tend to the diffusion of knowledge. It is found in many instances quite impossible to prosecute studies at the colleges for various reasons. If private studies be recognized by the University, much good will be effected to the country at large, and a good deal of the drain on the public purse on account of higher education will be lessened.

The system of Government scholarships, at present followed in the Government schools, is also defective, as much as it gives undue encouragement to those classes only, who have already acquired a taste for education to the detriment of the other classes. The system might be so arranged that some of these scholarships should be awarded to such classes amongst whom education has made no progress.

The system of awarding them by competition, although abstractedly equitable, does not tend to the spread of education among other classes.

With regard to the question as to educated natives finding remunerative employments, it will be remembered that the educated natives who mostly belong to the Brahminical and other higher classes are mostly fond of service. But as the public service can afford no field for all the educated natives who come out from schools and colleges, and more over the course of training they receive being not of a technical or practical nature, they find great difficulty in betaking themselves to other manual or remunerative employments. Hence the cry that the market is overstocked with educated natives who do not find any remunerative employment. It may to a certain extent, be true that some of the professions are overstocked, but this does not show that there is no other remunerative employment to which they can betake themselves. The present number of educated men is very small in relation to the country at large, and we trust that the day may not be far distant when we shall have the present number multiplied a hundredfold, and all be taking themselves to useful and remunerative occupations and not be looking after service.

In conclusion, I beg to request the Education Commission to be kind enough to sanction measures for the spread of female primary education on a on a more liberal wale.

Joteerao Govindrao Phooley,

Merchant and Cultivator and Municipal Commissioner, Peth Joona Ganja.

Poona ,

19th October

1882