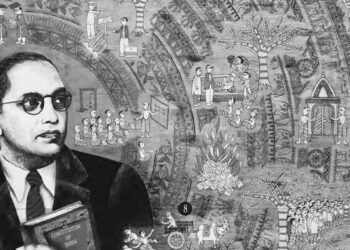

Paper read before the Anthropology Seminar of Dr. A. A. Goldenweizer at The Columbia University, New York, U.S.A. on 9th May 1916

Many of us, I dare say, have witnessed local, national or international expositions of material objects that make up the sum total of human civilization. But few can entertain the idea of there being such a thing as an exposition of human institutions. Exhibition of human institutions is a strange idea; some might call it the wildest of ideas. But as students of Ethnology I hope you will not be hard on this innovation, for it is not so, and to you at least it should not be strange.

You all have visited, I believe, some historic place like the ruins of Pompeii, and listened with curiosity to the history of the remains as it flowed from the glib tongue of the guide. In my opinion a student of Ethnology, in one sense at least, is much like the guide. Like his prototype, he holds up (perhaps with more seriousness and desire of self-instruction) the social institutions to view, with all the objectiveness humanly possible, and inquires into their origin and function.

Most of our fellow students in this Seminar, which concerns itself with primitive versus modern society, have ably acquitted themselves along these lines by giving lucid expositions of the various institutions, modern or primitive, in which they are interested. It is my turn now, this evening, to entertain you, as best I can, with a paper on “Castes in India: Their mechanism, genesis and development”.

I need hardly remind you of the complexity of the subject I intend to handle. Subtler minds and abler pens than mine have been brought to the task of unravelling the mysteries of Caste; but unfortunately it still remains in the domain of the “unexplained”, not to say of the “un-understood” I am quite alive to the complex intricacies of a hoary institution like Caste, but I am not so pessimistic as to relegate it to the region of the unknowable, for I believe it can be known. The caste problem is a vast one, both theoretically and practically. Practically, it is an institution that portends tremendous consequences. It is a local problem, but one capable of much wider mischief, for “as long as caste in India does exist, Hindus will hardly intermarry or have any social intercourse with outsiders; and if Hindus migrate to other regions on earth, Indian caste would become a world problem.” Theoretically, it has defied a great many scholars who have taken upon themselves, as a labour of love, to dig into its origin. Such being the case, I cannot treat the problem in its entirety. Time, space and acumen, I am afraid, would all fail me, if I attempted to do otherwise than limit myself to a phase of it, namely, the genesis, mechanism and spread of the caste system. I will strictly observe this rule, and will dwell on extraneous matters only when it is necessary to clarify or support a point in my thesis.

Caste is not a physical object like a wall of bricks or a line of barbed wire which prevents the Hindus from co-mingling and which has, therefore, to be pulled down. Caste is a notion; it is a state of the mind.

To proceed with the subject. According to well-known ethnologists, the population of India is a mixture of Aryans, Dravidians, Mongolians and Scythians. All these stocks of people came into India from various directions and with various cultures, centuries ago, when they were in a tribal state. They all in turn elbowed their entry into the country by fighting with their predecessors, and after a stomachful of it settled down as peaceful neighbours. Through constant contact and mutual intercourse they evolved a common culture that superseded their distinctive cultures. It may be granted that there has not been a thorough amalgamation of the various stocks that make up the peoples of India, and to a traveller from within the boundaries of India the East presents a marked contrast in physique and even in colour to the West, as does the South to the North. But amalgamation can never be the sole criterion of homogeneity as predicated of any people. Ethnically all people are heterogeneous. It is the unity of culture that is the basis of homogeneity. Taking this for granted, I venture to say that there is no country that can rival the Indian Peninsula with respect to the unity of its culture. It has not only a geographic unity, but it has over and above all a deeper and a much more fundamental unity—the indubitable cultural unity that covers the land from end to end. But it is because of this homogeneity that Caste becomes a problem so difficult to be explained. If the Hindu Society were a mere federation of mutually exclusive units, the matter would be simple enough. But Caste is a parcelling of an already homogeneous unit, and the explanation of the genesis of Caste is the explanation of this process of parcelling.

Before launching into our field of enquiry, it is better to advise ourselves regarding the nature of a caste I will therefore draw upon a few of the best students of caste for their definitions of it:

(1) Mr. Senart, a French authority, defines a caste as “a close corporation, in theory at any rate rigorously hereditary : equipped with a certain traditional and independent organisation, including a chief and a council, meeting on occasion in assemblies of more or less plenary authority and joining together at certain festivals : bound together by common occupations, which relate more particularly to marriage and to food and to questions of ceremonial pollution, and ruling its members by the exercise of jurisdiction, the extent of which varies, but which succeeds in making the authority of the community more felt by the sanction of certain penalties and, above all, by final irrevocable exclusion from the group”.

(2) Mr. Nesfield defines a caste as “a class of the community which disowns any connection with any other class and can neither intermarry nor eat nor drink with any but persons of their own community”.

(3) According to Sir H. Risley, “a caste may be defined as a collection of families or groups of families bearing a common name which usually denotes or is associated with specific occupation, claiming common descent from a mythical ancestor, human or divine, professing to follow the same professional callings and are regarded by those who are competent to give an opinion as forming a single homogeneous community”.

(4) Dr. Ketkar defines caste as “a social group having two characteristics : (i) membership is confined to those who are born of members and includes all persons so born ; (ii) the members are forbidden by an inexorable social law to marry outside the group”.

To review these definitions is of great importance for our purpose. It will be noticed that taken individually the definitions of three of the writers include too much or too little: none is complete or correct by itself and all have missed the central point in the mechanism of the Caste system. Their mistake lies in trying to define caste as an isolated unit by itself, and not as a group within, and with definite relations to, the system of caste as a whole. Yet collectively all of them are complementary to one another, each one emphasising what has been obscured in the other. By way of criticism, therefore, I will take only those points common to all Castes in each of the above definitions which are regarded as peculiarities of Caste and evaluate them as such.

To start with Mr. Senart. He draws attention to the “idea of pollution” as a characteristic of Caste. With regard to this point it may be safely said that it is by no means a peculiarity of Caste as such. It usually originates in priestly ceremonialism and is a particular case of the general belief in purity. Consequently its necessary connection with Caste may be completely denied without damaging the working of Caste. The “idea of pollution” has been attached to the institution of Caste, only because the Caste that enjoys the highest rank is the priestly Caste: while we know that priest and purity are old associates. We may therefore conclude that the “idea of pollution” is a characteristic of Caste only in so far as Caste has a religious flavour. Mr. Nesfield in his way dwells on the absence of messing with those outside the Caste as one of its characteristics. In spite of the newness of the point we must say that Mr. Nesfield has mistaken the effect for the cause. Caste, being a self-enclosed unit naturally limits social intercourse, including messing etc. to members within it. Consequently this absence of messing with outsiders is not due to positive prohibition, but is a natural result of Caste, i.e. exclusiveness. No doubt this absence of messing originally due to exclusiveness, acquired the prohibitory character of a religious injunction, but it may be regarded as a later growth. Sir H. Risley, makes no new point deserving of special attention.

Source: Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar

Writings and Speeches Vol:1,

Published by Education Department

Government of Maharashtra, 1979