Paper read before the Anthropology Seminar of Dr. A. A. Goldenweizer at The Columbia University, New York, U.S.A. on 9th May 1916

(Continuing from the previous issue)

This completes the story of those that were weak enough to close their doors. Let us now see how others were closed in as a result of being closed out. This I call the mechanistic process of the formation of caste. It is mechanistic because it is inevitable. That this line of approach, as well as the psychological one, to the explanation of the subject has escaped my predecessors is entirely due to the fact that they have conceived caste as a unit by itself and not as one within a System of Caste. The result of this oversight or lack of sight has been very detrimental to the proper understanding of the subject matter and therefore its correct explanation. I will proceed to offer my own explanation by making one remark which I will urge you to bear constantly in mind. It is this: that caste in the singular number is an unreality. Castes exist only in the plural number. There is no such thing as a caste: There are always castes. To illustrate my meaning: while making themselves into a caste, the Brahmins, by virtue of this, created non-Brahmin caste; or, to express it in my own way, while closing themselves in they closed others out. I will clear my point by taking another illustration. Take India as a whole with its various communities designated by the various creeds to which they owe allegiance, to wit, the Hindus, Mohammedans, Jews, Christians and Parsis. Now, barring the Hindus, the rest within themselves are non-caste communities. But with respect to each other they are castes. Again, if the first four enclose themselves, the Parsis are directly closed out, but are indirectly closed in. Symbolically, if Group A wants to be endogamous, Group B has to be so by sheer force of circumstances.

Now apply the same logic to the Hindu society and you have another explanation of the “fissiparous” character of caste, as a consequence of the virtue of self-duplication that is inherent in it. Any innovation that seriously antagonises the ethical, religious and social code of the Caste is not likely to be tolerated by the Caste, and the recalcitrant members of a Caste are in danger of being thrown out of the Caste, and left to their own fate without having the alternative of being admitted into or absorbed by other Castes.

Caste rules are inexorable and they do not wait to make nice distinctions between kinds of offence. Innovation may be of any kind, but all kinds will suffer the same penalty. A novel way of thinking will create a new Caste for the old ones will not tolerate it. The noxious thinker respectfully called Guru (Prophet) suffers the same fate as the sinners in illegitimate love. The former creates a caste of the nature of a religious sect and the latter a type of mixed caste. Castes have no mercy for a sinner who has the courage to violate the code. The penalty is excommunication and the result is a new caste. It is not peculiar Hindu psychology that induces the excommunicated to form themselves into a caste; far from it. On the contrary, very often they have been quite willing to be humble members of some caste (higher by preference) if they could be admitted within its fold.

But castes are enclosed units and it is their conspiracy with clear conscience that compels the excommunicated to make themselves into a caste. The logic of this obdurate circumstance is merciless, and it is in obedience to its force that some unfortunate groups find themselves enclosed, because others in enclosing, themselves have closed them out, with the result that new groups (formed on any basis obnoxious to the caste rules) by a mechanical law are constantly being converted into castes to a bewildering multiplicity. Thus is told the second tale in the process of Caste formation in India.

Now to summarise the main points of my thesis. In my opinion there have been several mistakes committed by the students of Caste, which have misled them in their investigations. European students of Caste have unduly emphasised the role of colour in the Caste system. Themselves impregnated by colour prejudices, they very readily imagined it to be the chief factor in the Caste problem. But nothing can be farther from the truth, and Dr. Ketkar is correct when he insists that “All the princes whether they belonged to the so-called Aryan race, or the so-called Dravidian race, were Aryas.

Whether a tribe or a family was racially Aryan or Dravidian was a question which never troubled the people of India, until foreign scholars came in and began to draw the line. The colour of the skin had long ceased to be a matter of importance.” Again, they have mistaken mere descriptions for explanation and fought over them as though they were theories of origin. There are occupational, religious etc., castes, it is true, but it is by no means an explanation of the origin of Caste. We have yet to find out why occupational groups are castes; but this question has never even been raised. Lastly they have taken Caste very lightly as though a breath had made it. On the contrary, Caste, as I have explained it, is almost impossible to be sustained: for the difficulties that it involves are tremendous. It is true that Caste rests on belief, but before belief comes to be the foundation of an institution, the institution itself needs to be perpetuated and fortified.

Caste in the singular number is an unreality. Castes exist only in the plural number. There is no such thing as a caste: There are always castes. To illustrate my meaning: while making themselves into a caste, the Brahmins, by virtue of this, created non-Brahmin caste; or, to express it in my own way, while closing themselves in they closed others out.

My study of the Caste problem involves four main points: (1) that in spite of the composite make-up of the Hindu population, there is a deep cultural unity; (2) that caste is a parcelling into bits of a larger cultural unit; (3) that there was one caste to start with and (4) that classes have become Castes through imitation and excommunication.

Peculiar interest attaches to the problem of Caste in India today; as persistent attempts are being made to do away with this unnatural institution. Such attempts at reform, however, have aroused a great deal of controversy regarding its origin, as to whether it is due to the conscious command of a Supreme Authority, or is an unconscious growth in the life of a human society under peculiar circumstances. Those who hold the latter view will, I hope, find some food for thought in the standpoint adopted in this paper.

Apart from its practical importance the subject of Caste is an all absorbing problem and the interest aroused in me regarding its theoretic foundations has moved me to put before you some of the conclusions, which seem to me well founded, and the grounds upon which they may be supported. I am not, however, so presumptuous as to think them in any way final, or anything more than a contribution to a discussion of the subject. It seems to me that the car has been shunted on wrong lines, and the primary object of the paper is to indicate what I regard to be the right path of investigation, with a view to arrive at a serviceable truth. We must, however, guard against approaching the subject with a bias. Sentiment must be outlawed from the domain of science and things should be judged from an objective standpoint. For myself I shall find as much pleasure in a positive destruction of my own ideology, as in a rational disagreement on a topic, which, notwithstanding many learned disquisitions is likely to remain controversial forever. To conclude, while I am ambitious to advance a Theory of Caste, if it can be shown to be untenable I shall be equally willing to give it up.

(Concluded)

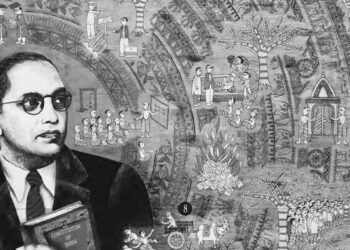

Source: Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar

Writings and Speeches Vol:1,

Published by Education Department

Government of Maharashtra, 1979