A. Raja

Member of Parliament

Former Union Minister

It remains essential even today to fight against the dark forces of communalism and to kindle the light of harmony

Fifty-six years after Jawaharlal Nehru left the world stage — his anniversary is May 27 — demagogic attempts are still being made to dub Nehruvian ideology as myopic. In the discussion on the dilution of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution in both Houses of Parliament, Nehru was not only criticised by the ruling party, but even lampooned.

The debate began with the opinion that Nehru had mishandled the Kashmir issue, and that had it been entrusted to Sardar Patel, as in the case of the other princely States, the end result would have been impeccable. Pertinently, one needs to understand the historical context and the point in time of Kashmir’s integration with India.

A dedication to integration

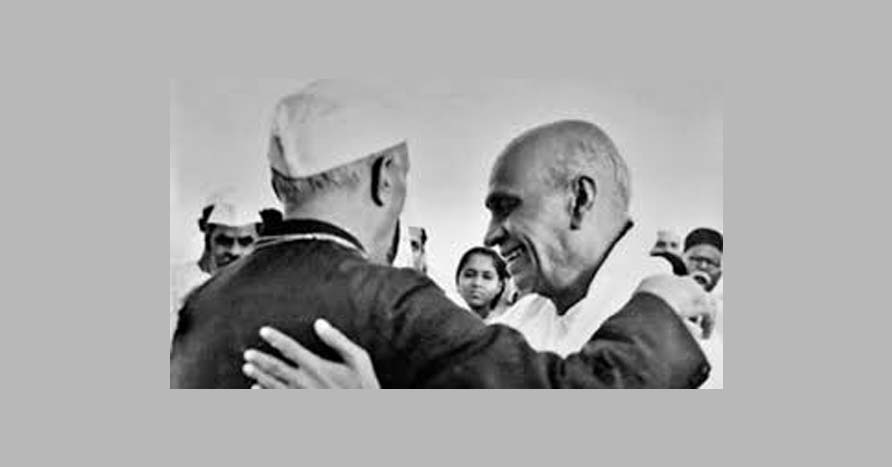

Mehr Chand Mahajan who served as the Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir in 1947-48, and later as Chief Justice of India, has recorded in his autobiography the entente between Nehru and Patel in the matter of Kashmir’s integration with India. On October 24, 1947, Mahajan received a late-night call from Deputy Prime Minister Sardar Patel asking him to come over to Delhi from Amritsar, in the same plane in which Lady Mountbatten was to go to Srinagar to meet the recently-freed Sheikh Abdullah with a message from Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. It is also important to note that Nehru was in the U.S. at this time and Patel was at the helm in India. Yet, the correspondence between Nehru and Patel during this period clearly captures a sense of camaraderie and sincere dedication to the goal of Kashmir’s integration with India. Even the letter drafted by Nehru addressed to Sheikh Abdullah was sent to Patel for his perusal through N. Gopalaswami Ayyangar. This then led to the initiation of administrative proceedings in the Constitutional Assembly. Even minor changes in the draft Article 370 were being apprised (with relevant clarifications) to Nehru by Patel, as seen in his letter dated November 3, 1949.

Article 370 was deemed temporary by both Nehru and Patel, but given Kashmir’s geography and its implications for India’s national security, that Constitutional provision was an urgent necessity. In its absence, Kashmir would have virtually atrophied.

Approaches of Nehru, Patel

Nehru’s sincere commitment to secularism, evinced in his espousal of the principles of religious equality, is being criticised either as “pseudo-secularism” that is biased in favour of the minorities or as an impractical exercise in futility given how the majority’s religion is compared to the minorities. The criticism is touted as if Patel and Nehru had divergent opinions on the meaning of secularism even though there is no such evidence. Granville Austin’s observation is relevant here: “Nehru and Patel were the focus of power in the Constituent Assembly, when they were divided on an issue, as in the case of property clause, factions could line up behind them and the debate would be lengthy. But when they settled their differences, the factions among the rank and file would do little else but shake hands and make the decision unanimous.” Patel’s view on secularism is moderate and as chairman of the advisory committee on fundamental rights, he had to review the report of the sub-committee on minorities in the Constituent Assembly. His tenor there was very much that India should follow the principle of secularism.

Nevertheless, Patel is often identified as a Hindu traditionalist. It is a historical fact that Hindu traditionalist leaders like Madan Mohan Malviya and Lala Lajpat Rai favoured the idea of an Indian nation built around the majority (Hindu) community to which Nehru was strongly opposed. When K.M. Munshi (then a Union Minister) tabled in Parliament the matter of reconstruction of Gujarat’s Somnath Temple which had been damaged by the army of Mahmud of Ghazni in the 11th century, Deputy Prime Minister Sardar Patel announced in November 1947, that the government would provide funds for rebuilding the temple. However, at the insistence of Nehru, Gandhiji suggested that the project should be financed by public subscription. Nehru was strongly committed to keeping the government distanced from religion — an attitude that defined the character of new-born India.

Nehru used every available opportunity to not only propound the benefits of a ‘socialistic democracy’ as opposed to the ‘Hindu Nation’ prescribed by the Hindu Mahasabha, but also to reassure India’s Muslim minority of their future in India. On the other hand, on June 6, 1948, Sardar Patel urged the Hindu Mahasabha to amalgamate with the Congress. He made similar pleas to the RSS.

In Sankar’s Sardar Patel: Select Correspondence (1945-50), we find that in May 1948, after Gandhi’s assassination, Nehru was anxious about the ‘recrudescence of the RSS’. Consequently, the RSS was banned. Golwalkar pleaded first with Nehru and then with Sardar Patel to lift the ban on RSS. At which point, Patel demanded that Golwalkar should put together a written constitution for the RSS. In the end of January 1949, the RSS’s official constitution came into being. However, Sardar Patel’s expectations were not met in this constitution and it became an exercise in futility. Golwalkar intended to launch an agitation from his place of detention. Finally, in June 1949, Patel agreed to accept an amended constitution and the ban on the RSS was lifted on July 11. Patel’s favourable inclination towards the RSS reached its peak when a resolution was passed in the Congress Working Committee (CWC) on October 10, 1949, authorising Swayam Sevaks to become members of the party — all during the absence of Nehru who was then travelling abroad.

The internal democracy within the Congress was also put to the test in 1950, when Purushottam Das Tandon was elected as party president by defeating Kripalani, with the support of Patel in recognition of his Hindu nationalist loyalties. Tandon emphasised two points at the Nashik Congress session: one was Hindu nationalism and the other was adoption of Hindi as an official language. Nehru as Prime Minister threw his weight against this emergent tense and prickly situation. He said, “… If you want me as Prime Minister, you have to follow my lead unequivocally. If you don’t want to me to remain, you tell me so and I shall go. I will not hesitate. I will go out and fight independently for the ideas of the Congress as I have done all these years.”

Need for science and logic

The approaches of Nehru and Patel in dealing with Hindu nationalist ideology may be divergent but they are clearly two sides of the same coin — that coin being secularism. History recounts that Patel’s approach was based on his faith and trust, not on logical inferences. Nehru felt that India needed to favour science and logic instead of orthodox religiosity. He believed that ‘education is meant to free the shackles of the human mind and not to imprison it in pre-set ideas and beliefs’. His motto, namely cultivating scientific temper and nurturing the spirit of tolerance are the foundations of his concept of secularism.

Consider Nehru’s commitment to the adoption of the Hindu Code Bill introduced by the then Law Minister B.R. Ambedkar. According to Ambedkar, “The Hindu Code Bill was the greatest social reform measure ever undertaken by the legislature in the country…..” The Bill was vehemently resisted by every Hindu nationalist in the Congress. President Rajendra Prasad even expressed apprehension that it may cause disruption in every Hindu family. Nehru’s inability to pass the Bill initially, forced Ambedkar to resign from the cabinet. However, Nehru’s continuous struggle to get the Bill passed (even if with some amendments) is credible testimony to his commitment to uphold secularism.

Nehru had dreamt for a modern India to have an exalted position on the world stage, rising above sectarian politics and divisive forces. In January 1948 he said, “As far as India is concerned, I can speak with some certainty. We shall proceed on secular lines… in keeping with the powerful trends towards internationalism.”

An effective democracy and the nurturing of unity and solidarity are the need of the day for our nation. Nehruvian ideology continues to remain essential even today to fight against the dark forces of communalism and to kindle the light of social harmony.

Courtesy: The Hindu