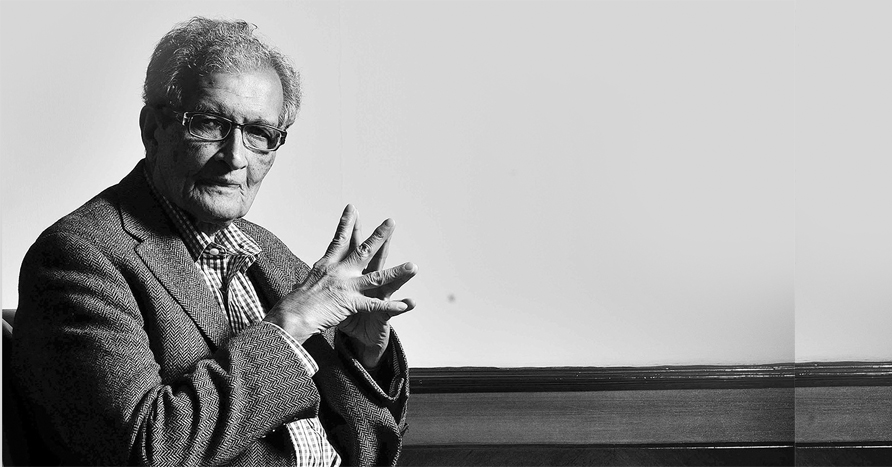

Winning cannot be the only concern in fighting an election.

It makes a big difference how the winners are

viewed in the post-election world.

– Amartya Sen

The excitements of the recent general elections are over and the results have been finalised. The totality of the lessons from the elections will, of course, take a long time to emerge with full clarity, but a few simple thoughts about the organisation and use of our electoral system seem immediate.

From the British, India has inherited a system of choosing the electoral winner on the basis of plurality — the candidate with most votes — who quite often does not have support from a majority of voters. The BJP won a majority of parliamentary seats, but it received only 37 per cent of the votes. Did the Opposition parties appreciate the difference between majority and plurality adequately?

Given the relative strength of the Bharatiya Janata Party, should there have been more alliances among the Opposition parties? Should the Congress have had more coordinated agreements with other anti-BJP parties, such as the Bahujan Samaj Party and the Samajwadi Party in Uttar Pradesh? Should there have been an alliance between the Aam Aadmi Party and Congress in Delhi, or between the Congress and Prakash Ambedkar’s party

in Maharashtra? Should the Rashtriya Janata Dal in Bihar, which did make alliances, have gone a step further in not denying room for the youthful national leader, Kanhaiya Kumar, in Begusarai, without worrying about Kumar being a potential rival to the leadership of the 29-year-old RJD leader, Tejashwi Yadav (a consideration that, it is widely alleged, led the coalition to decide on fatally splitting the anti-BJP vote)? There are many such questions to ask, at the individual as well as aggregative level.

No less importantly, should the coalitions that actually emerged have worked towards an agreed vision, and not been satisfied merely with the fact that the parties are “all anti-BJP”? I have argued elsewhere (in an opinion piece in The New York Times, May 25) that while the parties against the BJP were vocal enough on their shared dislike of the party, there was relatively little discussion on the basic ideological differences between the BJP’s perspective (particularly the philosophy behind the dominance of a religious identity — in this case, the “Hindu identity”), and the integrated vision of a common identity of Indians across the country (irrespective of religion). Indeed, the reasoning behind the powerful Gandhi-Tagore-Nehru vision of a united India, which had contributed to keeping India together for decades, received rather little attention. A positive vision can play a constructive and inspiring role, going well beyond negotiated, possibly ad hoc agreements — what can be called, in Hegelian language, “negation of negation.”

Turning now to the BJP, the winner, it has excellent grounds to be happy with the election results on May 23. And yet, the BJP leadership, and especially its highly talented and exceptionally ambitious top leader, Narendra Modi, have reasons to be disappointed by global reactions to the BJP victory. There has been widespread criticism in the news media across the world (from The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The Guardian, The Observer, Le Monde, Die Zeit and Haaretz to the BBC and CNN) of the ways and means of securing BJP’s victory, including instigation of hatred and intolerance of groups of Indian citizens, particularly Muslims, who have every right to be treated with respect (as under the Gandhi-Tagore understanding).

Winning cannot be the only concern in fighting an election. It makes a big difference how the winners are viewed in the post-election world. A well-wisher of the BJP would have had reasons to desire more than just a win for her favourite party.

What about the people at large? India is, in many ways, a successful democracy, which — until recently — had an excellent reputation for treating different political parties with symmetry and equity. However, in the 2019 elections, there have been reasonably convincing allegations of unequal favours received by the ruling party. These concerns have been partly related to the assessment of some of the decisions taken by the Election Commission, but they relate also to the unequal opportunities offered to the different parties by state-owned institutions (for example, state-owned Doordarshan gave the BJP about double the broadcast time in the crucial pre-electoral season, compared with what it offered to the Congress).

If India has to retain — and in fact regain — its past reputation for offering a level playing field to different political parties, these asymmetries would have to be removed, which is particularly important when the favoured player happens to be the ruling party in office, which appoints the administrative heads of state-owned enterprises, and which also has a bigger role in the appointment of the Election Commission.

Going further, the amassing of assets useable in elections of the different political parties has clearly been extraordinarily unequal in 2019. The BJP had many times more money and resources for electoral use than all its rivals, including the Congress. The need for effective rules and regulations for reducing such huge asymmetries is very strong indeed. This is important not only for the democratic credibility of India, but also for the way the victory of the electoral winners is judged, globally as well as locally.

India does not lack people with moral courage. Even though the resistance to injustice — economic, political, social and cultural — is easiest to articulate during electoral campaigning, the fight for fairness and justice is, in many ways, a continuous phenomenon in our country. But so are the attempts by the government to repress resistance. New restrictions have been imposed on the liberty of speech, which has included the imprisoning of people by branding dissent from the government’s super-nationalist beliefs as “sedition”. New categories of offence have also been invented, such as being described as an “urban Naxalite” on the basis of utterances that the government determines are dangerous, leading to house arrest or worse. The Indian courts have often intervened to restrain the government, but given the slow speed of legal processes in India, relief — even when it came — has taken a long time. And a number of intellectuals have been murdered for expressing views that the Hindutva movement finds objectionable.

The credit that the ruling party can get for winning the elections is seriously compromised by such repression. The victorious side has to consider what kind of regime it wants to run — and how it is viewed across the world. It is not hard to appreciate that democracy demands more than the counting of votes.

This article first appeared in the print edition of The New Indian Express on May 29, 2019 under the title ‘Judging a victory’.

Down south in Tamil Nadu, Sneha who became the first Indian to get a ‘no caste, no religion’ certificate, didn’t have it easy either. She also has to constantly face abuse and threats. The 35-year-old lawyer, who initiated the process to be officially without religion or caste in 2010, says that nothing had prepared her for the prodding questions or the barrage of criticism that came her way soon after she received the certificate from the Thasildar of Tirupattur, in February 2019.

“When I was enrolled in school, my parents left the sections stating caste and religion blank. There is no mention of caste or religion in any of my transfer certificates from school. I grew up with these values. For me, getting such a certificate was just one of the many ways to fight the caste system in India,” she said. When Sneha applied to obtain official recognition of her having no caste and religion, she kicked up a storm in official corridors.

“I was probed and probed on why I needed such a certificate and whether I would use it to get some government benefit. Many feared that such a certificate would have far-reaching implications and could even affect the reservation policy meant for marginalised people if more were inspired by me to follow suit,” she said.

But there have been those who supported Sneha and several who reached out to her, asking how they could get a similar certificate.

Ms. Sneha was felicitated for her sustained efforts to get ‘No Caste, No Religion’ certificate by Dravidar Kazhagam at the Birth Centenary celebration of E.V.R. Maniammaiar on 10th March 2019 in Vellore, Tamil Nadu.