This story was first published on January 26, 2016 (Towards Equality: Why did Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar publicly burn the Manusmriti on December 25, 1927). We are re-publishing it.

Manusmriti Burning Day

On December 25, 1927, huge strides were made in the movement for self-dignity of Dalits. Under the leadership of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, a small town/village, Mahad in Konkan, the coastal region of Maharashtra, made history.

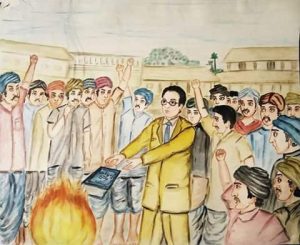

Manusmriti Burning Day, the day that the text of caste Hindus epitomizing hegemony, indignity and cruelty to Dalits and mlecchas (that included women) was publicly burned in a specially constructed symbolic funeral pyre before Dr Ambedkar and thousands of volunteers gathered to protest and agitate.

The Mahad satyagraha had been organised so that Dalits could drink from the Mahad (Chavadar) water tank, a public water source open to all. A previous legal notification of the Collectorate authorized free access to all.

Despite the existence of this order, caste hegemony and oppression had not created conditions for access to this facility for the oppressed. On the eve of the protest, caste Brahmins had obtained a stay order from a local court against untouchables accessing water from the tank!

Pressure of an unimaginable kind was put by caste Hindus to somehow abort the protest. This included tightening access to any public ground for the proposed meeting. Finally, a local gentleman Mr. Fattekhan, who happened to be a Muslim, gave his private land for the protest, extending solidarity with the struggle. Arrangements for food and water as also other supplies had to be made meticulously by the organisers facing a revolt in the village. A pledge of sorts had to be taken by the volunteers who participated in the protest. This pledge vowed the following:

I do not believe on Chaturvarna based on birth.

I do not believe in caste distinctions.

I believe that untouchability is an anathema to Hinduism and I will honestly try my best to completely destroy it.

I will not follow any restrictions about food and drink among at least all Hindus.

I believe that untouchables must have equal rights to access to temples, water sources, schools and other amenities.

The arrival of Dr. Ambedkar to the site of the protest was cloaked in high drama, faced with the possibilities of all kinds of sabotage from other sections of society. He came from Bombay on the boat “Padmavati” via Dasgaon port, instead of Dharamtar (the road journey), despite the longer distance. This was a well-planned strategy, because, in the event of boycott by bus owners, the leaders could walk down five miles to Mahad.

In front of the pandal where Dr Ambedkar made his address, the “vedi” (pyre) was created beforehand to burn the Manusmruti. Six people had been labouring for two days to prepare it. A pit six inches deep and one and half foot square was dug in, and filled with sandalwood pieces.

On its four corners, poles were erected, bearing banners on three sides. The banners said,

- “Manusmruti chi dahanbhumi”, i.e. Crematorium for Manusmruti.

- Destroy Untouchability

- Bury Brahmanism.

It was on December 25, 1927, in the late evening, at the conference, that the resolution to burn the Manusmruti was moved by Brahmin associate of Ambedkar, Gangadhar Neelkanth Sahastrabuddhe and was seconded by PN Rajabhoj, an untouchable leader. Thereafter, the book Manusmruti was kept on this pyre and burned. The Brahmin associate of Ambedkar, Gangadhar Nilkanth Sahastrabuddhe and five six other Dalit sadhus completed the task. At the pandal, the only photo placed was that of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. This has been interpreted to mean that, at this stage the Dalit leadership, including Dr. Ambedkar had yet to be disillusioned with Gandhi.

In his presidential speech Ambedkar said that the aim of the movement was not only to gain access to the water or the temple or to remove the barriers to commensality; the aim was to break down the varna system which supported inequality in society. He then told his audience about the French Revolution, and explained the main points of the Charter of Human Rights enunciated by the French Revolutionary Council. He pointed out the danger of seeking temporary and inadequate solutions by relating how the rebellion of the plebians of Rome against the patricians failed, primarily because the plebians sought only to gain a tribune of their choice instead of seeking to abolish the system dividing society into patricians and plebians.

In the February 3, 1928 issue of the Bahishkrit Bharat (his own newspaper) he explained the action saying that his reading of the Manusmriti had convinced him that it did not even remotely support the idea of social equality.

The root of untouchabilty lies in prohibition of inter-caste marriages, that we have to break, said Ambedkar in that historic speech. He appealed to higher varnas to let this “Social Revolution” take place peacefully, discard the sastras, and accept the principle of justice, and he assured them peace from our side. Four resolutions were passed and a Declaration of Equality was pronounced. After this, the copy of the Manusmruti was burned.

One sees here a definite broadening of the goal of the movement. In terms of the ultimate goal of equality and of the eradication of the varna system, the immediate programme of drinking water from the Mahad water reservoir was a symbolic protest, to herald the onset of a continuing struggle for dignity.

The other crucial points of Dr. Ambedkar’s speech were:

“…So long as the varna system exists the superior status of the Brahmans is ensured….Brahmans do not have the same love of their country that the Samurai of Japan had. Hence one cannot expect them to give up their special social privileges as the Samurai did in the interest of social equality and national unity of Japan. We cannot expect this of the non-Brahman class either. The non-Brahman classes like the Marathas and others are an intermediate category between those who hold the reins of power and those who are powerless. Those who wield power can occasionally be generous and even self-sacrificing. Those who are powerless tend to be idealistic and principled because even to serve their own interest they have to aim at a social revolution. The non-Brahman class comes in between; it can neither be generous nor committed to any principles. Hence they are preoccupied in maintaining their distance from the untouchables instead of with achieving equality with Brahmans. This class is weak in its aspiration for a social revolution…..We should accept that we are born to achieve this larger social purpose and consider that to be our life’s goal. Let us strive to gain that religious merit. Besides, this work (of bringing about a social revolution) is in our interest and it is our duty to dedicate ourselves to remove the obstacles in our path.

There was a strong reaction in the section of the press, perceived to be dominated by the entrenched higher caste interests. Dr Ambedkar was called “Bheemaasura” by one newspaper. Dr. Ambedkar justified the burning of Manusmruti in various articles that he penned after the satyagraha. In the February 3, 1928 issue of the Bahishkrit Bharat he explained the action to burn a thing was to register a protest against the idea it represented. By so doing one expected to shame the person concerned into modifying his behaviour. He said further that it would be futile to expect that any person who revered the Manusmriti could be genuinely interested in the welfare of the Untouchables. He compared the burning of the Manusmriti to the burning of foreign cloth recommended by Gandhi. Protests the world over had used the burning of an article that symbolised oppression to herald a struggle. This was what the Manusmurti Dahan was.

The tactical retreat

Meanwhile, condemned by a sudden Court ruling to hold back the satyagraha of drinking water from the public water tank, Dr Ambedkar explained the dilemma faced by on the one hand the government/British Collector and entrenched high caste interests.

In a note entitled ‘Why the Satyagraha was Suspended’ in the 3 February 1928 issue of the Bahishkrit Bharat, Ambedkar said, “The untouchables are caught between the caste Hindus and the government. They can attack one of the two. There is nothing to be ashamed of in admitting that today they do not have the strength to attack both of them at the same time. When the caste Hindus refused to concede the legitimate rights of untouchables as human beings willingly and on their own initiative, we thought it wise to arrive at a peace (agreement) with the government…… There is a world of difference between a satyagraha launched by caste Hindus and one launched by untouchables. When the caste Hindus initiate a satyagraha it is against the government and they have community support….. When the untouchables launch a satyagraha all the caste Hindus are arraigned against us.”

He observed further that the agitation of the untouchables was not limited to the Mahad water tank. It had been launched to achieve the larger goals the untouchables had set for themselves. The answer to whether it could have been sustained depended upon one’s estimate of the loss and the hurt that would have resulted from the satyagraha and the means that were available to protect the people from this loss and hurt. If the people had seen that they could not recover from the loss inflicted on them by one satyagraha in Mahad they would never rise again to join another satyagraha. This question had to be weighed.

What stands out is the openly rational, almost calculated approach to the strategy of the struggle and a willingness to present it as such. There is no effort to obfuscate or mystify it. Ambedkar responded to the concern that the withdrawal of the satyagraha would give caste-Hindu slanderers an opportunity to scoff at the untouchable leaders, by saying merely that he had not launched the satyagraha to win their approbation.

Courtesy: sabrang