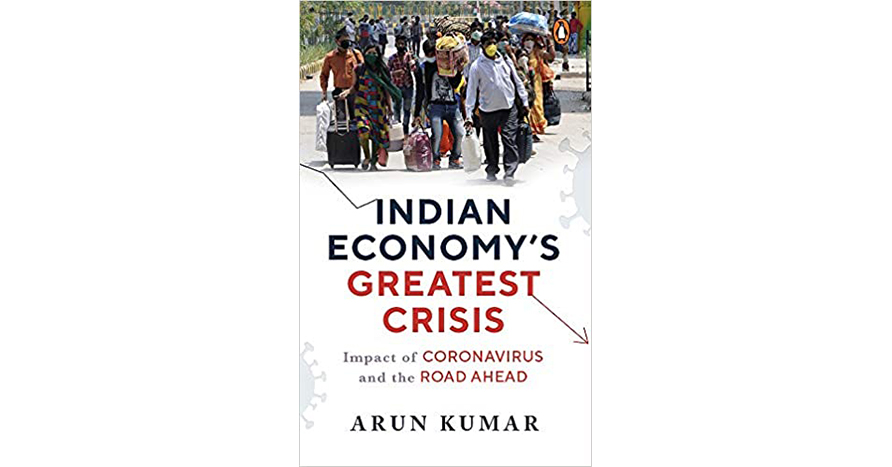

‘Indian Economy’s Greatest Crisis’ Arun Kumar, Penguin Random House, Rs.499/-

Kandaswami Subramanian

It is difficult to keep abreast of the flow of writings on the genesis and spread of the COVID-19 infection by medical experts and by economists on its economic impact. Medical pundits are puzzled over the spread, mutations, and so forth. Economists are in no better position to assess the impact.

On the health front, the worry was about the weak healthcare infrastructure which is patchy, mal-distributed, and not “universal.” Economists debated the near-total impact affecting all the sectors of the economy. The virus was playing havoc with both the supply and demand at the same time, a situation not met with in the past. A pandemic of enormous proportions should have alerted the global community and brought about a global coordination and action. This was missing.

Weaknesses exposed

Prof. Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel laureate, observed in a session of the UN General Assembly, “The crisis exposed weaknesses in economies, governments, and societies, with developed countries unable to produce basic products like masks and ventilators, as their populations suffered poor health without social protection.” Add to these the travails of the global slowdown, the growing protectionism, trade war, etc. The hope for a quick global recovery appeared to remain a “fantasy.”

India had its own story with a few distinguishing features rendering its struggle against the virus and holding the economy intractable. Arun Kumar highlights this in his new book, Indian Economy’s Greatest Crisis. It is ponderous in its scope, scholarly, and sober in its analysis, but it succeeds in giving flesh and blood to the issues raised by most critics intuitively.

A major part of the book is devoted to the sufferings of the migrant labour under lockdown. There is an analysis of the changed (and changing) nature of the complex modern economy in which labour is driven to live on subsistence wages. Chapter III studies, at length, how the lockdown hits the poor labourers hard. The next chapter goes into the nitty-gritty of the impact of the lockdown. Its predictions are dire and take into account the growing inequality and the rising new labour displacing technologies.

Finally, Arun Kumar draws attention to the failure of the government to boost demand while the misplaced emphasis was to look at the supply side. Even when an assistance programme was announced, it was too little and too late.

After the global financial crisis of 2008, India faced economic stagnation, marked by lower GDP rates, falling manufacturing and productivity, a decline in exports. The demonetisation move of 2016 had the most devastating effect on the economy, striking at the root of the informal economy encompassing tiny (village) and SME sectors as also millions of marginal or migrant workers.

It was against the twin weaknesses of public health infrastructure and the fragile economic structure that India had to combat the crisis. It was a daunting task and called for policy dialogues and action by the government after due diligence. Unfortunately, there was no consultation with either political parties or the public. Dr. Jayati Ghosh was forthright in saying that “the most destructive effect of COVID-19 in India was not due to the disease but the government’s response.” The book is like a compendium on the impact of the virus on the Indian economy and is a valuable contribution to the new genre of COVID economics.

Source : ‘The Hindu’