Manoj Mitta’s new book ‘Caste Pride’ looks at caste through the legislative and judicial lens

In the 1880s, a radical form of wedding took place in the Bombay Presidency, which did away with any kind of Brahmin priest. The moving force behind this reform was the Satyashodhak Samaj or the Truth Seeking Society established by social reformer Jotirao Phule in Poona in 1873 “to free the Shudra people from slavery to Brahmans…” There were back and forth legislations and post-independence too India was still grappling with the validity of a wedding without a Brahmin officiating at it. Manoj Mitta’s new book, ‘Caste Pride’, traces the many legal and judicial battles on caste, a defining feature of India’s public life. This edited excerpt is of one such battle that took place in Madras in the 1950s.

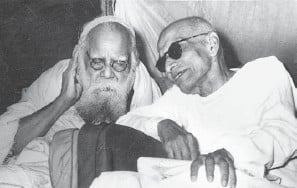

The catalyst for social change in Madras was the Self-Respect Movement led by Dravidian icon E.V. Ramasamy or Periyar. The question of whether a Hindu wedding could be valid without a purohit (priest) and his Brahmanical rituals was addressed for the first time by the Madras High Court in 1953. In its judgment on suyamariyadai or self-respect form of marriage, the overall signal was that the Shudras were required to maintain the semblance of a Hindu wedding even if only as a poor imitation of the ways of their social superiors.

As the judgment nullified all marriages that had been conducted in this fashion, it caused much consternation among the Self-Respectors in Madras state. This feeling gained piquancy because the judgment came at a time when the chief minister of Madras, Chakravarti Rajagopalachari alias Rajaji, was already embroiled in a caste controversy. Rajaji had introduced an education reform scheme, under which the hours of elementary schooling were reduced from five to three, so that children could spend the other two hours at home learning the occupation of their parents. Critics, like Periyar’s Dravidar Kazhagam and Annadurai’s Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam saw it as a Brahminical conspiracy to confine the children from lower castes to menial occupations.

‘Non-conforming marriage’

In this fraught environment, Rajaji’s governement drafted a bill in response to the High Court verdict on marriage. To the disappointment of Self-Respectors, the bill did not refer to their form of marriage by the name they have given it — suyamariyadai — instead, it cast it in negative terms, defining it as a ‘non-conforming marriage’. All it offered was a one-time amnesty scheme to those who had committed the folly of marrying in that non-conforming style. Those who wanted their self-respect marriages to be legalised would be allowed to register them within two years. Hence, the title of the bill was the ‘Hindu Non-Conforming Marriages (Registration) Bill’.

The Jawaharlal Nehru government noticed deficiencies when the state referred the bill to it on 12 December 1953 for its sanction, as per procedure. The Centre wrote back saying that, while it agreed that ‘legislation of the kind envisaged is necessary’, it suggested, in effect, an overhaul of the bill. For the self-respect marriages that had been held in the past, the Centre proposed that they be ‘validated directly without the further formality of registration’. In another sharp deviation from Rajaji’s plan, the Centre suggested ‘limiting the application of that formality to marriages which take place in the future’. It also specified that the Madras state should ‘in part follow the model’ of the colonial Arya Marriage Validation Act, 1937, which had breached the customary restrictions on inter-caste marriage for the Arya Samaj sect. In conclusion, it said that, after the incorporation of those changes, a copy of ‘the final draft may kindly be supplied to this Ministry before its introduction in the State Legislature’.

However, instead of making the proposed changes, Rajaji escalated the matter by writing a letter himself, addressed to Home Minister K.N. Katju. This was how Rajaji’s letter, dated 31 December 1953, opened: ‘My dear Katju, Referring to your Deputy Secretary’s (Sri N. Sahgal’s) letter… ’The manner in which he dismissed the Centre’s forward-looking ideas suggested that Rajaji, a lawyer himself, was counting on the weight of his personality to enforce his will. On the Centre’s reservations about the linking of validation with registration, Rajaji’s response smacked of orthodoxy. ‘A number of such marriages have taken place in the past and they are not recorded anywhere. No priests officiated and the usual accompaniments of a marriage according to custom were not present. It has, therefore, become necessary to provide for the parties to such marriages or their children to come forward to record these marriages. With this aim, the most easy form of procedure, namely, registration, has been provided in the proposed Bill.’

On ‘Suyamariyadai’

In much the same manner, he dismissed the relevance of the Arya Samaj legislation, which the Home Ministry had cited on the advice of the Law Ministry. The Arya Samaj law, he wrote, related to ‘the personal qualification of the parties to form a union’ across caste barriers. On the other hand, his concern about suyamariyadai was on ‘the adequacy of the form of marriage to give rise to the status of a lawfully wedded husband and wife’. Rajaji gave no indication why suyamariyadai could not be, like the Arya marriage, legislatively recognised on its own terms.

The bill did not pass into law. After it was cleared by the Madras Legislative Council, the bill remained stuck in the other House, the Legislative Assembly, where it was introduced on 7 May 1954. The official explanation for the stalemate was that ‘the Government did not proceed with the further stages of the Bill’. The real reason was that Rajaji had by then resigned. His sudden exit was because of growing opposition, even within the Congress party, to his education scheme and the fear that it was casteist in nature. His successor, K. Kamaraj, from the Nadar caste, abandoned not only Rajaji’s education scheme but also his bill to register non-conforming marriages.

It was in 1967 that the Annadurai government incorporated the suyamariyadai in the Hindu law.