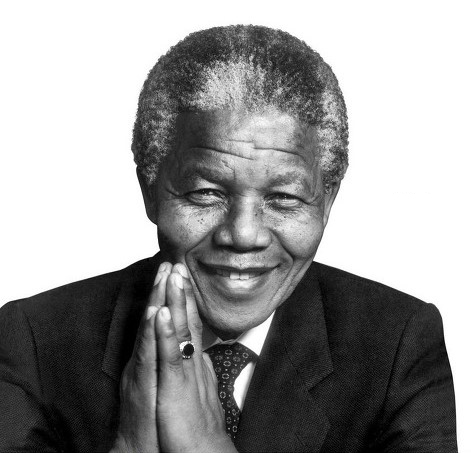

Aakar Patel

Columnist and translator of Urdu and Gujarati Non-fiction works

Bhagat Singh’s well-argued essays are evidence of his maturity

Bhagat Singh died at 23 having led a full life. At 21 he threw bombs on the parliament building that India is about to abandon. Having spent two years in jail he was hanged in March 1931, though he demanded to be shot. I say he led a full life because he managed to become mature in his short youth, leaving us material that gives evidence of his maturity.

His collected writings are a slim volume, only 100 pages or so. The main piece in it is his essay on why he is an atheist. It is written as an apologia, a formal defence of his opinion. He penned it in jail, while awaiting execution — which makes it even more interesting. He felt compelled to write it because someone (we are not told who) had commented that Singh was an atheist because of vanity — implying that he thought too highly of himself to submit to an almighty.

My reward

At 22 (the essay was written in October 1930), Singh had become a national celebrity. His act of rebellion, his desire not to harm the enemy — the bombs were only whiz-bangs that produced smoke — and his ability to express himself clearly ensured that the media and the public were riveted to him. His good looks added to his charms and there was almost nobody across the political spectrum who didn’t support him. This might have led to the accusation that he thought too much of himself.

Singh defends himself against this in the beginning though he seems to make too much of the accusation. It is when he gets over his eagerness to show he is not narcissistic that his writing becomes beautiful. He accepts that belief has its uses — it softens hardship and can even make it pleasant. Then he asks what he gains by rejecting belief at this point in his life. The judgment is to come in a week’s time, he writes, and he knows what it is going to be. He will be hanged. If he had been a believer he would have had the solace of going to a better place, but he is convinced no god exists.

He writes: “I see that a short life of struggle with no such magnificent end shall itself be my reward. That is all. Without any selfish motive of getting any reward here or in the hereafter, quite disinterestedly have I devoted my life to the cause of freedom. I could not act otherwise.”

Standing for it

This is not the thinking of an average 22-year-old. Clearly, while he had absorbed his fame and was aware of it, he had been contemplating other things as he awaited death. Singh quotes Upton Sinclair and Darwin as he discusses the differences between various faiths and death.

He ends the essay with these lines: “One of my friends asked me to pray. When informed of my atheism, he said, ‘When your last days come, you will begin to believe.’ I said, ‘Never. I consider it to be an act of degradation and demoralization. For such petty and selfish motives, I shall never pray.’

Reader and friends, is it vanity? If it is, I stand for it.”

It becomes clear on reading this and Singh’s other essays why he has remained vivid in our imagination almost a century after his death. Singh was hanged in Lahore’s Shadman Chowk on March 23, 1931. About a decade ago, a group of Pakistanis petitioned their government to honour Singh (who had been born on the Pakistan side of Punjab). In 2012, the place was renamed Bhagat Singh Chowk.

Source:‘The Hindu’