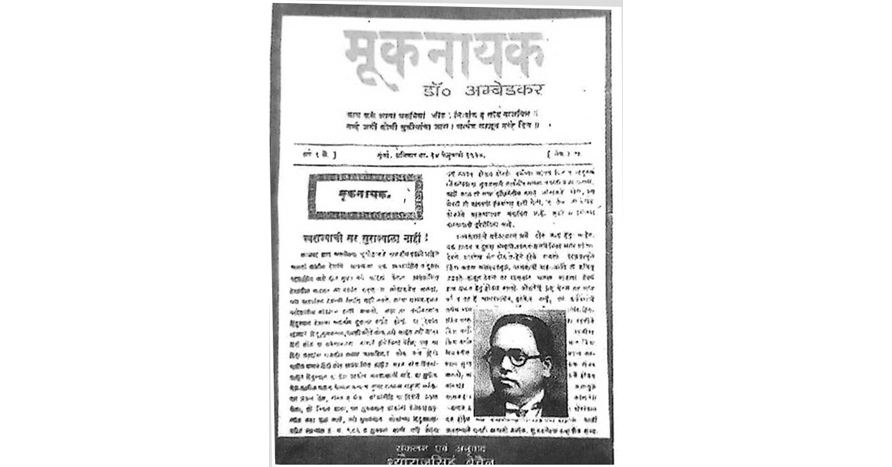

In the centenary year of ‘Mooknayak’, the Marathi journal published by B.R Ambedkar, here is an extract from the inaugural issue where Babasaheb lashes out against caste discrimination

Mooknayak (The Leader of the Mute), the first journalistic venture of Babasaheb Ambedkar, was a fortnightly newspaper he started in 1920 with the patronage of his mentor, Shahuji Maharaj. Ambedkar’s aim in launching this journal was to put forward his own point of view on matters such as Swaraj, the education of the ‘untouchables, and the evils of untouchability, which had hitherto not found due representation in mainstream Hindi journals. Mooknayak remained in circulation for three years. This is an excerpt from the editorial of the inaugural issue, which appeared on January 31, 1920.

If anyone were to take stock of the sum-total of all the elements, of human as well as non-human origin, which constitute the fabric of our nation, it would doubtless be revealed that India is most distinguished by the many disparities which characterise its composition. Among these disparities the most shameful is that which manifests itself in acute inequalities in material standards of living.

Although Indians stand divided by many kinds of differences, the differences in religious affiliation are potentially more dangerous than those stemming from physical or intellectual factors. Often the differences on the basis of religion find expression in such extremities of conduct that they are the cause of bloodshed. The distinctions between the Hindus, the Parsees, the Jews. the Muslims and the Christians, and various other denominations. take diverse forms, but close scrutiny bears out that the stark hiatus between Hindus of different orders is both as reprehensible as it is incredible.

If a European is asked who he is, the answer provided by him, indicating his nationality — English or German or French or Italian — as it may be, will be enough to resolve the matter. The same cannot, however, be said about Hindus. The statement, “I am a Hindu”, satisfies nobody. It is, necessary for a Hindu to declare his caste in order to spell out his specific identity.

The castes which constitute the so-called Hindu community are arranged in hierarchical order. Hindu society is like a tower, each floor of which is allotted to one caste. The point worth remembering is that this tower has no staircase and therefore there is no way of climbing up or down from one floor to another. The floor on which one is born is also the floor on which one dies. No matter how meritorious a person from a lower floor might be, there is no avenue for him to climb up to the upper floor. Likewise, there is no means by which a person entirely devoid of merit can be relegated to a floor beneath the one to which he has been assigned.

The interrelationship between castes is not founded upon the logic of worth. However unworthy an upper caste person might be, his status will ever remain high. Similarly, a worthy lower caste person will never be allowed to transcend his lowness. Because of the strict taboos against inter-dining and inter-marriage between members of lower and upper castes, the respective caste bodies are destined to remain always already segregated from each other. Even if bonds of intimacy are kept outside of consideration within the realm of caste relations, there is close surveillance of possibilities of contact which might transgress caste laws. While some castes are permitted limited mobility within the caste structure, some other castes, branded ‘impure’, are denied such movement altogether. The latter are the ‘untouchable’ castes whose ‘impure’ nature poses a threat of contamination to all caste Hindus.

At the pinnacle of the caste hierarchy are the Brahmins who regard themselves as the Gods of the earth. All other men and women have been born to serve them, or so they seem to believe. Hence they feel absolutely entitled to claiming the devotion of these sub-ordinates. The Brahmins are convinced that they have earned their dues by their authorship of the sacred scriptures of the Hindus, notwithstanding the illiberal lessons which are preached through these texts. The non-Brahmins, on the other hand, have remained backward due to lack of possession of adequate property and education. But their backwardness does not necessarily entail the misery caused by total deprivation because they have never lacked the means of subsistence obtainable from agricultural and industrial occupations, trade and commerce and other employment opportunities. The worst victims of social discrimination have been the outcastes who find themselves impoverished, weak and lacking in self-esteem, and thus it is their sorry plight which needs to be consciously highlighted. Their only redemption lies in their self-emancipation from their chains of bondage, a process which has now happily begun. Unfortunately, there is yet hardly any institutional forum of communication, any media resource, which is yet prepared to foreground, frankly and fearlessly, the numerous problems which beset the outcastes. There are, no doubt, a few newspapers and journals which raise issues connected with the due need for re-solution of the problems facing the so-called lower castes, but none of these really give exclusive attention to the question of the rights of the ‘untouchables’. It is for the purpose of filling up this void that the period-ical called Mooknayak has been planned and put into circulation.

Translated from Marathi to Hindi by Prof. Sheoraj Singh Bechain, Department of Hindi, University of Delhi; arid from Hindi to English by Dr. Tapan Basu, Department of English, University of Delhi.

Courtesy: ‘The Hindu’