Politics was never about facts alone, and perceptions play a major role. No one in the DMK could effectively counter Jayalalithaa’s attempt to project herself as a victim. When the DMK returned to power, President R.Venkataraman realized that he needed to back Jayalalithaa to keep Karunanidhi in check. He also convinced Rajiv Gandhi that the Congress needed a partner with a mass base to face the parliamentary election. V.P.Singh’s association with the DMK made it easy for Rajiv Gandhi to support Jayalalithaa. First, he used his offices to initiate a dialogue between the two factions of the ADMK. On 10 February 1989, the two ADMK factions united and the next day, they were granted the ‘Two Leaves’ symbol of the undivided party by the Election Commission. The Chief Election Commissioner R.V.S. Peri Sastri, said in his order that ‘following the withdrawal of both the petitions filed by Ms. Janaki Ramachandran and Ms. Jayalalithaa, the dispute raised by them on the symbol no longer existed’.

The Congress was desperate to distract people’s attention from the Bofors deal. The alignment with Jayalalithaa helped the Congress to manage the headlines better in Tamil Nadu. In this process, four significant contributions of Karunanidhi’s government did not get their due attention. The first was the opening of a new building to house the Madras Metropolitan Development Authority. It was called Thalamuthu Natarajan Maaligai, in memory of the two anti-Hindi activists who died in police custody. Second was the creation of universities devoted to a speciality. Tamil Nadu, which was the first state to establish dedicated universities to further domain expertise by starting the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University and Anna university for Engineering and Technology, expanded the ambit further in 1989. karunanidhi laid the foundation stone for the Dr MGR Medical University and merged various institutions dealing with veterinary sciences to form the Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University. Third, for the first time in India, a scheme for free electricity to farmers was introduced. Fourth, 30 per cent reservation for women in government jobs was introduced.

During this term, he divided the total 50 per cent rerservation meant for the backward classes into the categories of backward classes (BCs) and most backward classes (MBCs) and allotted 30 per cent and 20 per cent reservation for them respectively. Pattali Makkal katchi (PMK), which was demanding a special reservation for MBCs, was not satisfied with the allocation of 20 per cent, but the DMK reached out to Vanniyars through its own Vanniyar leaders such as Veerapandi Arumugam, Gingee Ramachandran and Durai Murugan to break the myth that the Pattali Makkal katchi was the sole representative of the Vanniyars. In his final term as the chief minister, from 2006 to 2011, 3.5 per cent was reserved newly for the BCs among Muslims, reducing the 30 per cent reservation to 26.5 per cent for the rest of the BCs.During the same tenure, he brought in the provision of a new reservation of 3 per cent for Arundhathiyars, who belong to the lower rungs of the Scs, out of the total reservation for scheduled castes of 18 per cent.

The Dravidar Kazhagam president, K.Veeramani observed:

Owing to the new reservation measures brought by Kalaignar, among the downtrodden sections of BCs and SCs, many people who had either not availed of reservation or those who had either not availed of reservation or those who had lesser share of reservation or those who had lesser share of reservation were able to get the desired share. The new quota among the SCs has enabled people from the Arundhathiyar community, who were traditionally carrying out scavenging work, to become doctors and teachers of higher academic institutions and enter other fields for the first time.”

Apart from running the state government, he devoted substantial time to explain the Dravidian Movement’s feature of social justice to V.P.Singh. Starting with the publication of the ‘Non-Brahmin manifesto’ in 1916 to the first-ever affirmative action in India through the Justice Party government’s ‘communal government orders’ of 1921-’22, that introduced reservation on the basis of caste, Karunanidhi explained the difference between the two political trajectories—the one based on social justice and the other rooted in poverty alleviation. He said the poverty alleviation trajectory rarely acknowledges the humiliation that is heaped on people because of their birth.

Karunanidhi pointed out to V.P.Singh his role in the elevation of the then district judge, A.Varadarajan, as a judge of the Madras High Court. This elevation, which made Varadarajan the first scheduled caste judge of the High Court, was a silent revolution. This imnitiative of Kalaignar’s further enabled Justice A.Varadarajan to become the first scheduled caste judge of the Supreme Court. Clearly, Karunanidhi was animated by the Mandal Commission’s recommendations. When news about his relentless pursuit of the reservation leaked, the old charge against Karunanidhi—that his affirmative action was seen as casteist—came back in the form of Chinese whispers.

He recollected his own response made in 1971 against casteist slurs on the floor of the Legislative Assembly and asked the DMK cadres to follow similar principles in dealing with criticism from those who are against any affirmative action. H.V.Hande, a member of the Swatantra Party, much to the chagrin of the treasury benches, called the DMK government a ‘third-rate government’.

Karunanidhi asked his colleagues to remain calm, and replied, ‘The honourable member from the Opposition mentioned our government as a third-rate one. I would like to say, in fact, I’m proud to say that our government is not a third-rate government but a ‘fourth-rate government’. Yes, fourth in the hierarchy of the varnashrama dharma, viz. sudra. Our government is the government of sudras, by the sudras and for the sudras.’ That retort worked as an effective pushback, both in 1971 and in 1989, to the campaign against social justice but it failed to generate any electoral dividend.

The parliamentary elections in November 1989 may have been a body blow to Rajiv Gandhi and his party. Though the Congress was still the largest party, with 197 seats and 39 per cent of the vote, it had lost 218 seats. In any case, Rajiv was in no position to form a government, as he candidly told President R.Venkataraman. But his loss was less humiliating as compared to the crushing defeat faced by Karunanidhi and the DMK. The ADMK-Congress alliance won thirty eight of the thirty nine seats in Tamil Nadu and DMK lost all the seats it contested, except for its ally CPI winning one seat in Nagapattinam. Jayalalithaa and her spin doctors used the electoral victory to reiterate that she was treated disgracefully in the Assembly. To borrow a phrase from S.Guhan, Karunanidhi was a ‘particularly non-Teflon coated leader’ and the charges of misogynistic behaviour stuck. It paved the way for a huge shift of women voters away from the DMK.

It was neither a smooth nor a straight journey for his friend V.P.Singh as well. The newspapers reported that on 2 December the National Front leader Vishwanath Pratap Singh (V.P.Singh) was sworn in as prime minister and Devi Lal, as deputy prime minister. But the reports did not explain DEvi Lal’s simultaneous induction as number two in the ministry and the hectic parleys that went on behind the scenes. Citizens of India overlooked the nuances hidden in the presidential notification issued in 1 December evening after the president gave V.P.Singh the ‘go-ahead’ signal. ‘Since the Congress (I), elected to the ninth Lok Sabha with the largest membership, it said, ‘has opted not to stake its claim for forming the government, the president invited Mr. V.P.Singh, leader of the second largest party/group, namely, the Janata Dal/National Front to form the government and take a vote of confidence in the Lok Sabha within 30 days of his assuming office.’ ‘The president, it was clear, would have called Rajiv Gandhi, re-elected leader of the Congress parliamentary party, had the Congress shown interest. Venkataraman, obviously, did not accept the doctrine enunciated by several constitutional authorities that a ruling party, on losing majority in the election, is not qualified for a bid at office, even if it emerges as the largest single group, and that precedence needs be given to the second largest party.

At this point, two states—Bihar and Tamil Nadu—came together to establish a government that reflected the will of the people. Lalu Prasad Yadav, who was credited for the Janata Dal tally of thirty two Lok Sabha seats in Bihar and Karunanidhi whose contributions to the numerical strength was zero, deciphered the 1989 parliamentary verdict better than the warring leaders of the Janata Dal, Janata Dal president, Mr. Chandra Shekhar was not in favour of V.P.Singh, but no MP from Bihar, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh favoured Chandra Shekhar and the latter’s choice, Devi Lal, was demurred in two quarters—the Left and the BJP, whose external support was crucial to securing the majority in the House.

It was the joint efforts of Lalu Prasad Yadav and Karunanidhi to press for the services of Biju Patnaik to sort out issues within the Janata Dal, statewise. For instance, in Karnataka, Ramakrishna Hegde and Deve Gowda went for each other as Gowda could never come to terms with Hegde’s role in making S.R.Bommai, the chief minister. A compromise formula was worked out where some positions were created at the state level and some at the central level to accommodate various aspirants. They also took up ways to find common ground between the National Front and the two ideologically opposed political blocks—the Left and the BJP. After many rounds of discussions held in Orissa Bhavan and Bihar Bhavan, Lalu Prasad and Karunanidhi persuaded Devi Lal to give up his demand for prime ministership and instead accept a twin offer, of deputy prime ministership to him and chief ministership of Haryana to his son, Om Prakash Chautala. From Bihar, the cabinet berths would go to George Fernandes, Ram Vilas Paswan and Sharad Yadav, and in Karnataka, Hegde would not be inducted in the cabinet but would be accommodated as deputy chairman of the Planning Commission.

V.P.Singh wanted the DMK to join the cabinet, despite not winning a single Lok Sabha seat. He told Karunanidhi, ‘I am not talking about numbers here, I am talking about political imagination. I am taking up this job knowing pretty well that the government may not last a year, and I will be pulled down sooner rather than later. I am doing it because of what you said about the transformative possibility of governmental power. Inducting the DMK in the cabinet will give me the moral courage to carry out some far-reaching decisions.’

Karunanidhi gave his consent to have his parliamentary party leader in the Rajya Sabha, Murasoli Maran, inducted into the government. Maran became the urban development minister.

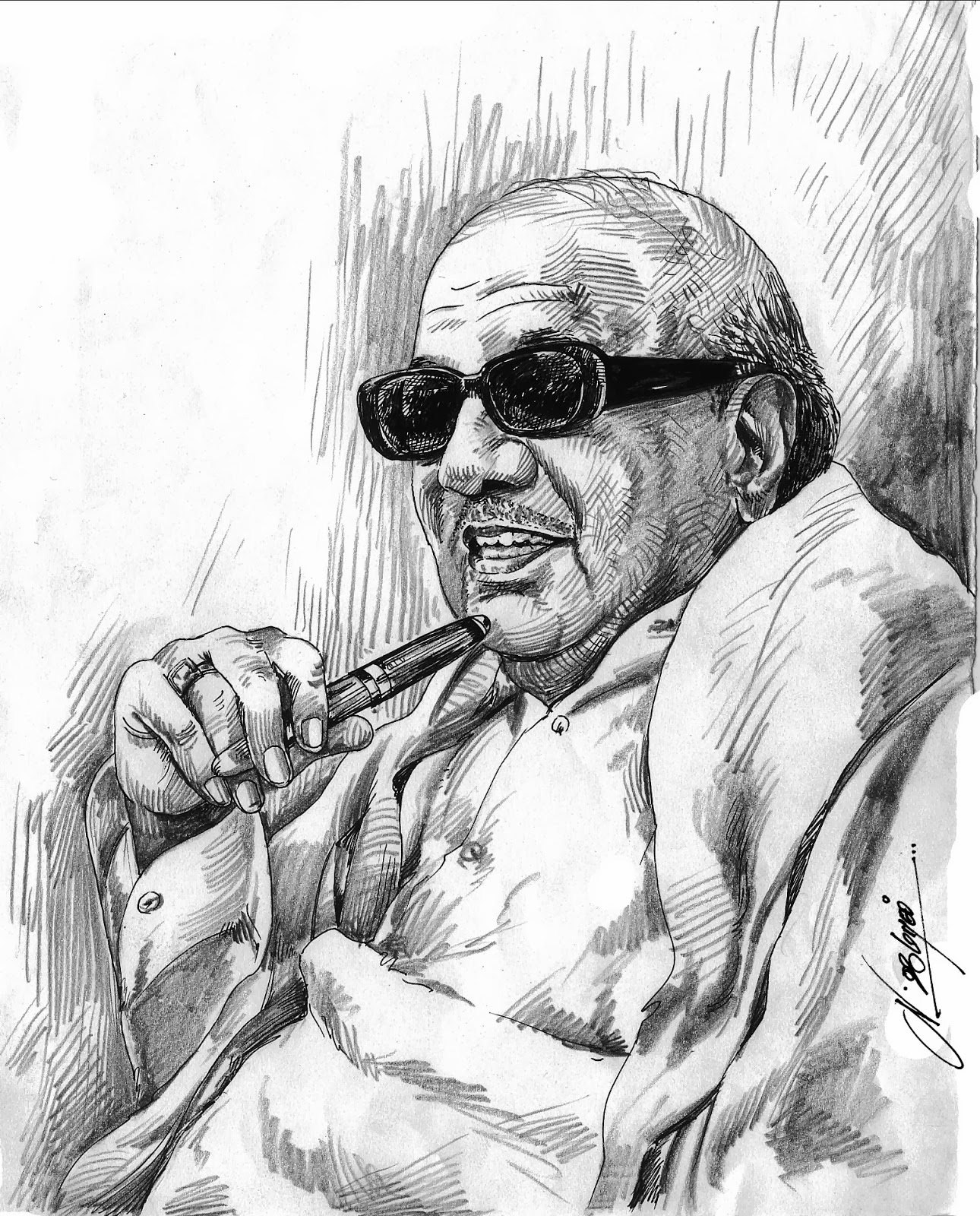

Karunanidhi was in a sombre mood when he recalled V.P.Singh’s regime. His interview with me lasted two hours and was full of anecdotes, besides dwelling on the ever-present fight in India between those who want an egalitarian society and those who want to see the entrenchment of the privileged classes. ‘At one level, it looked as if the DMK was in power both at the Centre and the State, and at another level, there were forces that were working for our downfall. My government in Tamil Nadu lasted 24 months, and the life of V.P.Singh’s government was 11 months. Both of us knew that our governments will not last and hence, there was a sense of urgency in implementing some of the far-reaching reforms,’ said Karunanidhi.

In a first, the Supreme Court bench led by Chief Justice Ranganath Mishra realized that the Central government’s attempt at a negotiated settlement of the Cauvery water dispute had failed to produce any result for two decades, and hence, he recommended adjudication, as a last resort. In accordnace with Section 4 of the Inter-State Water Disputes Act, 1956, the National Front government headed by V.P.Singh constituted the Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal on 2 June 1990 with Chittatosh Mookerjee, retired chief justice of the Bombay High Court, as chairman and N.S.Rao, retired judge of the Patna High Court, and S.D.Agarwala, retired judge of the Allahabad High Court, as members. V.P.Singh took this decision, despite having more MPs from Karnataka supporting his government, and no one from Tamil Nadu in the treasury benches in the Lok Sabha. ‘I am really at a loss to find adequate words to thank V.P.Singh for setting up the tribunal rather than yet another committee for a negotiated settlement as earlier prime ministers have done,’ said Karunanidhi.

While Karunanidhi rated the implementation of the Mandal Commission recommendations as the most important achievement of V.P.Singh, he felt two other crucial policy decisions failed to attract serious attention: the establishment of Prasar Bharti in November 1997 and the withdrawal of the Indian Army from Sri Lanka in 1990. He was convinced that the implementation of the Mandal Commission recommendations delayed the ascendance of the Hindu Right by two decades, and that everyone should be thankful to him for keeping it at bay between 1990 and 2014.

When V.P.Singh wrote to all the chief ministers on 12 June 1990, asking for their suggestions to implement the recommendations of the Mandal Commission, the Tamil Nadu goivernment was the first to make an elaborate presentation. It came up with a clear timeline for implementation, and suggestions to measure the social transformation due to affirmative actions. The recommendations were formally accepted by the Central government on 7 August 1990. In his speech in the Rajya Sabha, V.P.Singh said: ‘This is the realization of the dream of Bharat Ratna Dr B.R.Ambedkar, of the great Periyar Ramasamy, and Dr Ram Manohar Lohia.’

The BJP confronted Mandal with temple politics. Its president, L.K.Advani, sought to travel across the country to mobilize support for the temple. The party was busy projecting Mandal as a divisive plank, and the building of a temple by destroying a 400-year-old mosque, as a unifying initiative, Karunanidhi said, for him, that was the moment when George Orwell’s predictions came true for the second time. In his understanding, Advani’s policy reflected the fears that Orwell spoke of in his dark and dystopic masterpiece, Nineteen Eighty-four: ‘War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength.’ Wanting to extend his support to V.P.Singh, Karunanidhi invited him to host the National Integration Council (NIC) meeting, for the first time ever, in Madras. At the Madras meeting of the NIC, held on 22 September 1990, it was resolved to urge all parties to wait for the court ruling in the Babri Masjid-Ram Mandir case. Lalu Prasad Yadav, one of the participating chief ministers, told Karunanidhi that he would not permit Advani’s chariot to travel through Bihar. Karunanidhi added: ‘[The] Hindutva forces will keep inventing charges to discredit Lalu and myself as we remain the primary opponents to their hate project.’

Advani, who started his Yatra from Somnath in Gujarat on 25 September, reached Bihar on 22 October 1990. Advani contacted some of the cabinet colleagues of V.P.Singh and asked them to instruct Lalu Prasad Yadav to permit his journey through Bihar, without any incidents. When Home Minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed had asked V.P.Singh to let the procession go on, Lalu angrily retorted: ‘You all are intoxicated by power.’ On 23 October, Lalu ordered the arrest of Advani, and the BJP withdrew its support to the National Front government on 24 October. V.P.Singh had to face an internal revolt by a faction led by Chandra Shekhar, who worked out a deal with the Congress to form an alternative government. V.P.Singh resigned on 7 November, Chandra Shekhar, backed by the Congress, became the prime minister on 10 November.

Karunanidhi felt that V.P.Singh’s steadfast commitment to social justice , at the cost of losing his government, deserved popular appreciation. He invited the ex-prime minister for a statewide tour of Tamil Nadu that began in Madras on 8 December and ended in Nagercoil on 12 December. (It is another issue that the overwhelming reception accorded to V.P.Singh became the primary cause for prime minister Chandra Shekhar to dismiss the DMK government within a couple of months.) The cavalcade which left Madras would have six to seven pit stops before culminating in a public meeting in the evening. At major centres like Trichy, Madurai and Tirunelveli, the meeting assumed the character of a state conference. It was also an emotional moment when the veteran Left leader E.M.S.Namboodiripad decided to address some of these meetings. Namboodiripad said: ‘People are used to having a victory rally when someone comes to power. But, here in Tamil Nadu, there is a rally to celebrate a person, even though he has lost power. This shows the character of not just V.P.Singh but also the courage displayed by Karunanidhi. I am aware of the danger this move could lead to. I have the experience of the dismissal of my government in 1959. In 1969, my government fell because of engineered defections. Hence, I use the word “courage” carefully and consciously.’ Maran was the translator for V.P.Singh at all the venues.

At the state level, Karunanidhi considered his enactment of the equal inheritance right in 1989 as a major achievement. Till then, the property and succession rights of sons and daughters within Hindu families were different. While sons could exercise complete right over their father’s property, daughters enjoyed this right only until they got married. The Self-Respect Conference held in Chingleput in February 1929 had passed a resolution demanding equal rights for women. In 1989, the Hindu succession (Tamil Nadu Amendment) Act, 1989, finally provided equal succession rights. This law has had an understated yet significant impact in addressing gender inequality. At the natiomnal level, the law was amended only in 2005, when the DMK joined the Union government as a constituent of the UPA.’

The campaign to oust the DMK began the day Chandra Shekhar came to power. In 1976, the DMK government was dismissed, based on a dossier prepared by the Intelligence Bureau. M.K.Narayanan, the officer-in-charge of Tamil Nadu in 1976, was brought back as the director of the Intelligence Bureau. His appointment made it clear that the Congress was calling the shots. In order to firm up its alliance with the ADMK, the Congress wanted the dismissal of the DMK government. The Intelligence Bureau produced a dossier that said that the DMK was harbouring the LTTE and had failed to curb terrorism in the state. If the 1976 dossier touted corruption, the 1991 dossier touted terrorism. Buit, unlike 1976, the Centre had to deal with a governor who was refusing to sign on the dotted line.

Surjit Singh Barnala came up with a number of counter questions. He pointedly asked the home ministry, for instance how come there were no entries about the DMK’s alleged actions, before the rally for V.P.Singh. He said that he was from Punjab and had seen enough of these games. He declared that he would not be a party to such a treacherous move that undermined the federal balance of the country. When he was transferred to Bihar, following his refusal, he chose to resign from governorship. The governmenmt, headed by Chandra Shekhar, dismissed the Karunanidhi ministry on 30 January 1991, using the ‘otherwise’ provision in Article 356 of the Constitution, after Barnala’s refusal to make a recommendation for dismissal.

(Source: Kaunanidhi A Life, A.S.Panneerselvam)