LAW AND RELIGION – WILL THE TWAIN (N) EVER MEET?

It has been a long, long journey for the fourth varna (shudra) in the lowest rung of Hindu hierarchy to achieve equality, which is their birth right in law and now constitutionally guaranteed. The battle is not yet over, but there have been many milestones, legislations and judge-made law and the journey’s end as for as law is concerned is still at a distance.

Constitution and religion

Article 25 ensures right to freedom of religion. It incidentally provides for a restriction in Article 25.2 as under:

“(2) Nothing in this article shall affect the operation of any existing law or prevent the State from making any law

(a) regulating or restricting any economic, financial, political or other secular activity which may be associated with religious practice;

(b) providing for social welfare and reform or the throwing open of Hindu religious institutions of a public character to all classes and sections of Hindus.”

Article 26 while conferring the right to every religious denomination to manage its own affairs, makes it clear that the right to manage the affairs of any religious denomination is restricted to matters of religion only.

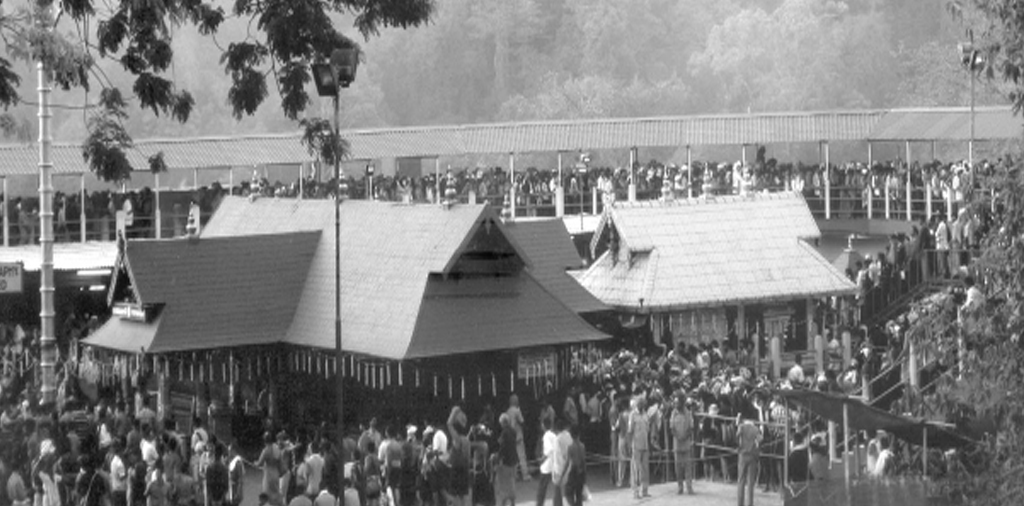

Temple entry

Madras Temple Entry Authorisation Act, 1947 was subject to challenge in its constitutional validity as if it is infringing Article 26(2) of the Constitution. The Supreme Court in Sri Venkataramana Devaru v. State of Mysore AIR 1958 SC 255 has held, that religious freedom is subject only to what is construed as customary religious practice under Article 26(2)(b). It does not mean all the practices followed are sacrosanct, but only those which are “essential and integral” as was reiterated in Durgah Committee, Ajmer v. Syed Hussain AIR v. 1961 SC 1402.

Regulation of Temple Administration

Madras Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowment (Amendment) Act, 1971 after having amended the 1959 Act dispensed with the principle of hereditary succession for office bearers and servants apparently with a view to include archakas too.

Seshammal’s case

The 1971 amendment to Madras Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowment Act, 1959 (HRCE) was the subject matter of challenge with reference to Article 26(2) of the Constitution before the Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court in Seshammal v. State of Tamil Nadu (1972) 2 SCR 11, a locus classicus on the subject. The Constitution Bench upheld the validity, so that “next in line” or heredity stood abolished once for all. It however, required “the appointment of office bearers or servants of the temples following the Agamas i.e. treatises pertaining to matters like construction of temples; installation of idols and conduct of worship of the Deity.”

Adithyan’s case

The Supreme Court following Seshammal’s case ruled out the claims of Namboodiri Brahmins objecting to any person other than those from their caste for appointment in N.Adithyan v. Travancore Devasom Board (2002) 8 SCC 106. The claim was dismissed on the opinion of a Vedic scholar of undisputed repute, that caste was not one of the requirements to be an archaka in Vedas. It is, therefore, well-established that apart from hereditary principle, the caste hegemony was also ruled out.

Appointment of Archakas

Rule 12 of the Madras Hindu Religious Institutions (Officers and Servants) Service Rules, 1964 required that an Archaka should be proficient in Mantras, Vedas, Prabandams etc., and be fit and qualified for performing puja and have knowledge of the rituals and other services. In answer to the argument before the Constitution Bench in Seshammal’s case, that an appointment by Notification is a power, by which any one can be made an archaka, the Court pointed out to section 28 of the Tamil Nadu Act already provides that the affairs of the trust should be governed “in accordance with the usage governing the temple”. In Sri Venkataramana Devaru’s case, the Supreme Court did point out to the need for compliance with the Agamas or ceremonial law relating to the construction of temples, installation of idols therein and conduct of worship of the deity.

Tamil Nadu Government G.O. 118 dated 23.5.2006

A Government Order (G.O.) No.118 dated 23.5.2006 was issued to the effect “Any person who is a Hindu and possessing the requisite qualification and training can be appointed as a Archaka in Hindu temples”. It is this Government Order, which was challenged before the Supreme Court on various grounds. The back-up of this G.O. was initiated by an Ordinance, which lapsed not having become law, but the G.O. was supported by the power available under the HRCE (Amendment) Act, 1971.

A Daniel come to judgement

The writ petition Civil No.354 of 2006 against the G.O.118 dated 23.5.2006 was filed and decided in a judgement of the Supreme Court in Adi Saiva Sivachariyargal Nala Sangam v. The Government of Tamil Nadu dated 16th December, 2015. This judgement is a veritable “Daniel come to judgement” following its earlier decisions and reiterating with support of treatise of Dr.S.Radhakrishnan, the philosopher-President, that a person chosen to be an archaka should be familiar with agamas and that the appointment of archakas should be strictly made on the basis of their qualification and training in the respective agamas. The relevance of agamas arises because of the difference between various sects in Tamil Nadu mainly between saiva and vaishnava traditions. The persons trained in one cannot be appointed to a temple consecrated for the other. It is only to ensure this direction, the Supreme Court had not merely dismissed the writ petition, but incorporated the direction that “appointment of archakas will have to be made in accordance with the agamas”.

The judgement is, therefore, a final victory on the part of those who desire the Hindu religion to be reformed and made more democratic with divestment of all vested interests. It is a development with which all the Hindus should rejoice as making their religion equally accessible with the same rights and duties for all Hindus. It is, therefore, unfortunate that more is read into the decision than what it lays down by wrongly interpreting the decision to be adverse to the Government and that status quo ante is restored.

There is absolutely no scope for any such misgiving as had been explicitly pointed out before the Press by Mr. K. Veeramani, the follower of Periyar and in his recent elaborate lecture explaining the decision in Tamil. Periyarists like other rationalists are happy that the dream and the last wish of Periyar is nearing realisation as symbolic of final victory in the battle for demolition of the caste hierarchy in the Hindu religion.

Religion was always subject to law and morality

H.M. Seervai in Constitutional History of India has pointed out after referring to Declaration of Human Rights “Again, in the free democracies, it is a matter of free choice for an adult person, whether to belong to any religion or not. He may not belong to any religion or he may change his religion”. He added that long before the Constitution, the law has always been recognised that the nexus of religion with untenable practices cannot be tolerated in what is famous as Maharaj Libel Case 1861, where a libel action by a person claiming to be a God, but suffering from venereal diseases, was not sustained, so that he had to leave the Court in dishonour and disgrace.

The Madras High Court in Gnana Sambandha Pandara Sannadhi v. Kandaswami (1886) ILR 10 Mad 375 upheld a decision, that an agreement by a Guru with his disciple to give him a gift of soul, body and wealth to him as his Guru making himself a slave, was void. The same view was taken in respect of an agreement obtained by a Mulla from his follower dedicating his tan (body), man (mind) and dhan (wealth) to himself, holding the agreement to be void. The power of excommunication, which a Mulla undoubtedly has, was faulted, when it was not justified on facts in respect of enforcement of rules and proper management of a dargah as decided by the Privy Council 1947 in Hasanali v. Mansoorali (75 I.A. 1.) .

The present development in Seshammal’s case (supra) culminating now in the recognition of the right of any Hindu to be archaka, if he is qualified, accords with fundamental principles, recognised under the Constitution, that religious power is not an absolute power to be preserved for all time to come. Religion has not only to move along with times. It cannot disregard the fundamental rights under the Constitution or Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The recent decision of the Supreme Court only confirms the role of religion as subservient to law and justice.

Thanks to Justice A.K.Rajan Committee spelling out the requirements of agamas, a large number of persons of all Hindu communities with requisite educational qualifications and the necessary training are available, so that absolutely there is no bar in giving immediate posting for the waiting candidates as archakas in temples for which their agama training suitably qualifies them.

Conclusion

Justice A.K. Rajan Committee spells out the requirements of agamas and the steps necessary to ensure its observance. There is a passing reference to the “offer” to adhere to the agamas in the affidavit of the State Government. It is described as “in-built admission” conceding flexibility in the operation of the impugned G.O., so that even the condition for compliance with the agamas is satisfied. A large number of persons of all Hindu communities with requisite educational qualifications and the necessary training are available, so that there is nothing standing in the way of immediate posting for the waiting candidates as archakas in temples for which their agama training qualifies them. If there is further delay, the only recourse for the trained candidates is to seek legal remedy after their having spent considerable time and expenses in getting the necessary training in the agamas.