Mark Kolsen

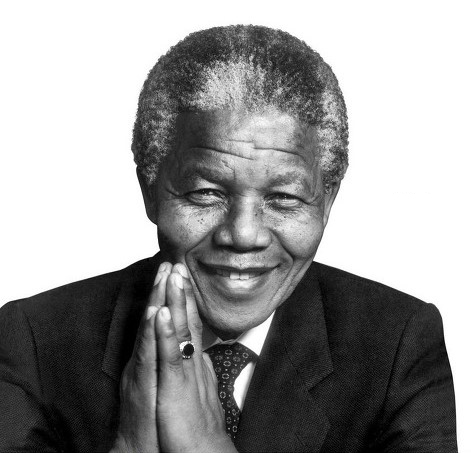

American Atheist

During his life and especially after his death in 2013, Nelson Mandela’s faith has been hotly debated. On the one hand are those such as British journalist Anthony Sampson, who, in his 1999 biography, flatly stated that Mandela “was not a formal believer like Oliver Tambo1; he did not quote the Bible or discuss theology. His interest in the Sunday services was more political than religious.” Sampson also wrote that Mandela “would never be a true believer.” In 2013, The Freethinker stated it is “widely understood” that Mandela was an atheist. Richard Dawkins and Steven Pinker retweeted the piece, to which Pinker added, “Nelson Mandela, great atheist—Hamba kakuhle, comrade!” Meanwhile, atheist blogger Hermant Mehta republished a piece from the Onion, which quoted Mandela’s words that “if you’re a 94-year-old man with a horrible lung infection, you need trained medical professionals. … All that prayer stuff is, frankly, pretty useless.” The obvious implication: only an atheist would make such a statement, especially near his death.

Responding to atheists’ evidence, Jacques Rousseau, a South African humanist and chairperson of the Free Society Institute, called it a “fabrication, or at least a fantasy, that [Mandela] was an atheist at all.” Mandela’s longtime friend Bishop Don Dabula unequivocally stated that Mandela “was a deeply religious man; he believed sincerely in the existence of the Almighty.” Michael Trimmer, in Christianity Today, went one better, writing that Mandela’s Christian faith is now “universally accepted,” a conclusion he based on words Mandela uttered when he attended church services during his presidency. Much more cautiously, Emily Murdoch, in World Religion News, wrote that because Mandela was very quiet about his religious beliefs, “History is still unsure of what Nelson Mandela’s exact beliefs were regarding god and religion.”

Amid the debate are those who have wondered if Mandela’s faith really matters. They have argued that a good man is a good man, no matter what his faith. What matters was his leadership in overturning apartheid in South Africa. And why bother to debate an issue Mandela himself refused to address? These writers, I would argue, are missing an important point, and in addition to examining the evidence on both sides of the debate, I will show that Mandela’s faith—which I will call “Ubuntu atheism”—does matter because it offers important lessons for leaders today.

Theists’ ‘Evidence’

In The Spiritual Mandela: Faith and Religion in the Life of Nelson Mandela (2018), South African journalist Dennis Cruywagen admited that after his release from prison in the 1990s, Mandela stated in an interview that “No, I am not particularly religious or spiritual. Let’s say I am interested in all attempts to discover the meaning and purpose of life. Religion is an important part of that exercise.” But Cruywagen then presented evidence “from many people who can testify to having witnessed his spiritual side.” They include Methodist prison chaplain Dudley Moore and Anglican priest Harry Wiggett who said that Mandela took communion regularly in prison, while Methodist president John Scholz told Cruywagen that Mandela not only accepted communion in his presence but encouraged the prison chaplain to do the same. In 1990, Mandela also took communion at a Catholic church, a controversial act that Rome questioned.

But while Cruywagen offers all these examples as evidence of Mandela’s “religiosity,” he completely ignores Mandela’s motives not only for taking communion but also for writing (in his autobiography) that while he was in prison, “I never missed a service and often read the scripture lessons. Come to think of it, I was quite religious.” In fact, Cruywagen—who rarely quotes Mandela himself—seems oblivious to what Mandela means when he uses the term religious and why he often called himself “a Christian.” Mandela subscribed to the missionaries’ axiom that “to be Christian was to be civilized, and to be civilized was to be Christian.” But to him there was a huge difference between being “religious” or “Christian” and believing in the supernatural.

Cruywagn’s other evidence is equally problematic. He interviewed a professor who told him that when Mandela was asked about his belief in Jesus Christ, Mandela answered that “a person’s relationship with God is personal and private, but a belief in Jesus is accepted by all of us.” Mandela typically distinguished between “God” (a word he rarely used) and “Jesus,” a biblical figure whose revolutionary spirit he admired. In fact, he justified using violence against the apartheid regime by recounting the biblical story of Christ’s throwing money changers out of the temple. Cruywagen unwittingly concedes this point when he quotes Peter Storey, who helped elect members of South Africa’s truth commission. Storey told Cruywagen that Mandela “was never a formal believer in sense of all the doctrinal jots and titles, but the spirit of Jesus and his welcoming spirit, I think, were profoundly central to his own character.”

Occasionally, Cruywagen misrepresents the nature of Mandela’s relationships. For example, Cruywagen says Mandela divorced Evelyn (his first wife) because he “did not share” her faith. This is an understatement: Mandela himself attributed the breakup to Evelyn’s efforts to “teach me the value of religious faith” and her “indoctrination” of their children, both of which he could not stomach. And Cruywagen completely ignores strong evidence that Mandela—a handsome, well-built “ladies man” who loved to “dress up”—was also a bit of a philanderer. In fact, in Fatima Meer’s biography (Higher Than Hope, 1988) Evelyn is quoted at length about the women with whom Mandela allegedly had affairs and attributes their divorce to Mandela’s infidelity. Mandela was raised in Xhosa culture, which has no prohibition against polygamy; Mandela’s own father had four wives.

Finally, aware that most of his evidence derives from “witnesses” other than Mandela himself, Cruywagen trumpets Mandela’s Methodist burial service as “a final salute to the church that had cultivated his spirituality, and … an answer to those who had always questioned his religious beliefs, or who had thought of him as an atheist … or an enemy of the Christian faith.” But—as Cruywagen admits—it was not solely a “Methodist” service; the funeral was “an eclectic mix of traditional rituals, Christian elements, and the military honors of a state funeral,” with many different religions represented. Although much grander, Mandela’s funeral resembled the funeral of his father, who was a pagan and, like other Xhosas, had no belief in an afterlife. Moreover, by 2013, no one could possibly have considered Mandela “an enemy of the Christian faith.” His atheism, however, is another matter to which we now turn.

The Core of Mandela’s Atheism

To understand Mandela’s unique brand of atheism, one must first understand Ubuntu, the philosophical ideal he learned as a young member of the Xhosa nation. Claire E. Oppenheim,4 in her article “Nelson Mandela and the Power of Ubuntu” for the journal Religions, explains that Ubuntu means “I am because we are” and is “an innate duty to support one’s fellow man,” a duty to foster “the spiritual growth of one’s community.” In contrast to descriptive words such as faith, grace, or divine, Ubuntu prescribes “that only through harmonious integration into one’s community of fellow man can oneself become more genuinely human.” Specifically, it requires that this integration be accomplished through “face-to-face positive interaction with one’s community members.” Throughout his or her life, a person can have more or less Ubuntu.

According to Oppenheim, “a close reading of [Mandela’s] oeuvre shows that he was much more strongly influenced by [his Xhosa’s] form of African humanism than Christian theology.” Oppenheim understates the evidence: even a perfunctory reading of Mandela’s works and biographies reveals that during and after his imprisonment, he did everything possible to “harmoniously integrate” with every person he encountered, i.e., to gain Ubuntu. In prison, he went to extraordinary lengths to befriend everyone—imprisoned political enemies, judges, priests, visiting state authorities, prison warders … you name it! As the religious were his only regular visitors (family could visit only once every six months), he did everything possible to make them feel welcome, including taking communion. To ensure he kept in contact with all inmates, Mandela attended different religious services (mandatory for all prisoners) every week. He counseled younger, angry prisoners how to live harmoniously with prison authorities. When he was told of his impending release from prison, Mandela even requested a one week postponement—after twenty-two years!—so that he could take the time to properly thank the prison authorities who had treated him so kindly.

Some observers, including his former fellow prisoners, have argued that Mandela’s Ubuntu was politically motivated. And it’s true, as Sampson notes, that Mandela “worked very hard to dialogue with everyone in prison to provide the basis for unity later outside” when he was released. Mandela was always confident that apartheid would fall, and that it would be replaced by a “rainbow” government embraced by all South Africans, Afrikaners included. Especially after his arrival in prison, where he learned to control his temper, he saw every person he met as a coalition partner in the future government he would lead, and he used his legal skills to persuade them of his righteous cause. To Mandela, “cooperation and goodwill” were the essential elements in creating that post-apartheid government. When the African National Congress (ANC) won the famous 1994 election, Mandela even cheered the party’s failure to win a two-thirds supermajority because the ANC’s 62 percent victory would require it to cooperate with other parties in a coalition.

But politics aside, one cannot overstate the degree to which Mandela practiced his tribe’s philosophical ideal. After his release from prison, Mandela sought out his persecutors. Sampson notes he “seemed like the legendary ex-convict who hunts down the people who betrayed him, but instead of murdering them, he forgave them.” Mandela’s old friend Thomas Huddleston—who believed in “holy anger”—was, Sampson says, “dismayed to watch him forgiving men who had opposed sanctions and connived with apartheid.” Sampson also observed that Mandela’s “capacity for seeing the best in people, his belief in the dignity of man, his forgiving” nature, made him seem religious. “Some visitors found him positively Christlike.”

Christianity’s Influence

Many authors have noted that Mandela often acknowledged Christianity’s influence on him, especially with his education. While his father rejected Christianity and saw no distinction (in Mandela’s words) “between the sacred and secular, between the natural and supernatural,” he agreed with Nelson’s mother that he should attend a Methodist primary school. There was really no choice; as Mandela later noted, unlike government-run schools, religious schools fostered an environment conducive to learning. Moreover, “Since the turn of the century, Africans owed their educational opportunities primarily to the foreign churches and missions that created and sponsored schools.” Mandela also attended secondary school and college at religious schools. They were, for Blacks, the only route for upward mobility, the only escape from menial, low paying labor to which most Blacks were condemned. What Mandela called “civilized” Blacks—those who worked as clerks, interpreters, policemen, and farmers using updated technology—were trained at religious schools. In fact, Mandela often used the term Christian as a synonym for a well-educated person with a solid education and job or—in other words—for someone who was (in his words) “civilized.”

From primary school through college, Mandela was required to attend religious services. While at home, religion was—in Mandela’s words—“a ritual that I indulged in for my mother’s sake and to which I attached no meaning.” At school, “religion was part of life’s fabric.” He attended church every Sunday with the regent, who became his guardian when Mandela’s father died when Mandela was nine. In college, he joined the Student Christian Organization, which did service projects such as teaching Bible classes to local villagers.

However, from Mandela’s autobiography, it’s evident that his oft-quoted appreciation for Christianity’s influence on him had little to do with theology. Beginning with his secondary education at Clarkesbury, he observed Black instructors who challenged White authorities; as a result, he began to redevelop his “Xhosa identity.” That identity was further fostered by his history courses, which taught him “how Africans were a conquered people.” With Christian teachers preaching that “all men are created equal in the eyes of god,” Mandela adopted a “creed … the creation of one nation out of many tribes, the overthrow of white supremacy,” and the establishment of “democracy” by means of “African militarism.” Everyone—Afrikaners included—was to be included. In Christian schools, Mandela also learned that leaders are like shepherds who learn to listen to every person, a principle of leadership he astutely practiced. In fact, he wrote that “Oftentimes, my own opinion will simply represent a consensus of what I heard in a discussion.” Later, whenever his ANC colleagues outvoted him on any issue, Mandela always acceded to the majority’s will.

It should be added that Christian schools also instilled in Mandela a deep distrust of “atheistic” communism. Although he later worked closely with communists in the ANC and considered their contributions vital to the struggle against apartheid, Mandela always denied being a communist—and once denied being an atheist—primarily because he considered both to be rigid, non-inclusive identities dominated by Whites. And in contrast to communists, Mandela saw racial, not economic, oppression at the root of South African apartheid. To him, South African communists were not only misinformed but an ideologically driven, divisive minority; “religious” persons, on the other hand, were more inclusive, an opinion that Mandela especially held after 1980, when many different churches began speaking out more aggressively in opposition to the apartheid system. At age seventy-nine, Mandela said, “Religious organizations played a key role in exposing apartheid. for what it is—a fraud and a heresy. It was encouraging to hear of the god who did not tolerate oppression but who stood with the oppressed.”

Nelson Mandela with Fidel Castro. Credit: Antonio Marin Segovia – Flickr.

Dialectical Materialism

Mandela’s distrust of “atheistic communism” dissipated after he studied Marxism and encountered Fidel Castro and Jawaharlal Nehru, whose works he read at length. According to Sampson, the readings “swept away” any remaining superstitions and inherited beliefs of Mandela’s childhood. Sampson says Mandela “experienced some pangs at abandoning the Christian beliefs that fortified his childhood,” but Mandela himself wrote that “Dialectical materialism seemed to offer both a searchlight illuminating the dark night of racial oppression and a tool that could be used to end it. … I was also attracted to the scientific underpinnings of dialectical materialism.” That “tool,” Mandela concluded in 1953, was violence, “the only weapon that would destroy apartheid” because nonviolence was an “ineffective weapon.” When the ANC’s Working Committee later challenged the timing of his conclusion, Mandela retorted that “Castro did not wait. He acted, and he triumphed.” After the Committee finally consented to Mandela’s plan, Walter Sislulu, at Mandela’s urging, traveled to China seeking arms. Mandela himself took the lead in organizing the ANC guerilla cells, though he insisted violence should aim to destroy infrastructure and minimize harm to humans. Violence should also be openly acknowledged and justified: in face-to-face discussions with the Afrikaner government, Mandela always stated that the nature of any conflict was defined by the oppressor, in this case, the violent apartheid regime, not the oppressed. When, during his prison term, that government asked him to renounce violence as a condition of his release, Mandela refused. No serious “Christian” would ever state such positions or take such actions.

The Neglected Prison Letters

Among all the evidence historians have presented about Mandela’s religious beliefs, I know of no source that has taken a hard look at Mandela’s prison letters, letters in which Mandela candidly wrote without worrying about his public image.5 His letters were often addressed to his family and friends, whom he greatly missed yet rarely saw. He could never be sure if a particular letter would be received, but especially when he learned of some tragedy—usually a death—he wrote lengthy letters expressing his condolences and empathy and tried hard to comfort the bereaved. These letters, I would posit, offer strong, much neglected evidence of Mandela’s atheism, perhaps stronger than any words he ever uttered in public.

Consider, for example, the many consoling letters he wrote to friends and family faced with illness or death. Not once did he ever offer supernatural consolation; in fact, when Winnie (his second wife) took ill, he wrote a letter encouraging her to “think positively” and to read the inspiring works of N. V. Peale, a Protestant clergyman who wrote books and columns extolling the power of positive thinking. But he noted that “I attach no importance to the metaphysical aspects of his arguments.” When his first son died—and much later, in 1986, when he wrote to a friend whose brother had died—Mandela only wrote of how tragic and stunning death is, especially the knowledge that “we would never see him again.” He always consoled the grieving not with images of an afterlife or God but by saying (as he did to a friend in 1985) that “When you are alone, you are never alone. There is always a haven of friends nearby.”6

Likewise, while in prison, Mandela deeply missed his daughters, who were often parentless during Winnie’s stints in jail. In addition to encouraging them to work hard and seek out friends when lonely, he often wrote revealing advice. For example, when, in 1978, his daughter Zizi told him of her weird dreams, he opined that perhaps she had an above average ability to foresee things. But he also wrote “There is nothing magical about this. What is certainly incorrect would be the belief that such powers are given to you by some supernatural being; that some events around you have a hidden meaning beyond the reach of science. … You will be safe if you always try to seek a scientific explanation for all that happens even if you come to a wrong conclusion.” In another letter, frustrated that his daughter might not be getting his birthday cards, he wrote, “These are the only occasions when I wish science could invent miracles” so that his daughter could receive the cards and know her father loves her.

As a final example, consider letters Mandela wrote to sociologist Fatima Meer, author of Mandela’s other biography. Responding to a mythological tale she had told him, Mandela wrote of mythology that his mother had “fed” to him since early childhood, but he begged off pondering Meer’s tale “lest we end up in the supernatural world.” He also wrote that “belief in the existence of beings with supernatural powers indicates what man would like to be and how through the centuries he has fought against all kinds of evil and strived for a virtuous life.” To my knowledge, Mandela never publicly stated his explanation for theism, as he well knew its atheistic implications. It should be added that through her entire biography, Meer says nothing about Mandela’s alleged “religiosity,” though she does offer some evidence that Winnie Mandela was an atheist.

Conclusion: The Efficacy of ‘Ubuntu Atheism’

Taught to seek Ubuntu and educated in Christian missionary schools, Nelson Mandela developed a strategy to overthrow the apartheid regime and establish a new government in South Africa. During both the struggle for, and the creation of, a new government, he believed all South Africans should be included. Although he wrote letters and editorials, Mandela recruited more followers with his Ubuntu, speaking face to face with everyone, including enemies, about the morality of his cause. Even when in jail, he showed that “retail politics” is a very effective means to “organize the masses” and develop a person’s role as a national leader.

At the same time, Mandela carefully cultivated a public image that would offend no one. To deflect questions about his religious beliefs, Mandela often claimed that religious beliefs were a “private affair.” This helped him counter every attempt by detractors to label him “an atheistic communist.” Yet his disbelief in the supernatural—his “covert” atheism—did not preclude him from embracing all religious denominations and participating in their rituals. Most observers—especially the religious—marveled at his “Christlike” behavior and accepted his rationale for the private nature of religious beliefs. One exception: Bishop Desmond Tutu, who was probably “on” to the fact that Mandela attended church not because he was a true believer, but for political reasons. As a careful listener and observer, Tutu intuited Mandela’s atheism when he said “[Mandela] would have won many others if (when he had gone to church and received communion) he would have made some reference to God.”

Yet, for all his “inclusiveness,” Mandela also understood that overthrowing an oppressive, powerful government might require violence, and by his own account this “tool” brought the apartheid regime to the negotiating table. During those discussions, he often told his oppressors, face to face, that after decades of fruitless talking, the ANC had no other choice. And after several decades of hard struggle, Mandela’s leadership strategy finally effected a historic regime change. Today, in our divided, identity-riddled world, where atheism and violence are often taboo and where politicians often use electronic media, detailed demographic profiles, and “identity politics” to attract support, the success of Mandela’s Ubuntu atheism offers future national leaders an alternative strategy worth pondering.

Notes:

1. Oliver Tambo was a South African anti-apartheid politician and revolutionary who served as President of the African National Congress (ANC) from 1967 to 1991.

2. In South Africa, the typical “civilized Christian” was the Englishman, who, Mandela once confessed, was “the very model of the gentleman for me.”

3. Mandela, especially in his youth, had (in Sampson’s words) “the confidence of a man about town, great presence and wide smile. … He kept his distance as befitted an aristocrat. He loved clothes, loved to change clothes; and was always fastidious about what he wore.”

4. Claire E. Oppenheim, “Nelson Mandela and the Power of Ubuntu.” Religions 2012, 3(2), 369–388; Available online at https://doi.org/10.3390/rel3020369.

5. “Mandela, like most great leaders, has always been a master of images who knows how to project himself.” (Sampson)

6. It should be added that in Mandela’s own accounts of how he intended to, and eventually succeeded in, overthrowing the apartheid regime, not once does he ever call on God for help in the struggle. To Mandela, the struggle was all about “the hand of the past” and the “power of the great cause that linked us all together.” By joining Christians, communists, tribal members, and even Afrikaners in an armed struggle, apartheid—Mandela believed—would fall. Likewise, while in prison—Cruywagen’s “witnesses” aside—Mandela never once called on God for help of any kind. He categorically believed that with all prisoners, including himself, “Our survival depended on understanding what the authorities were attempting to do to us, and sharing that understanding with one another.” In his autobiography, he also emphasized how visiting priests facilitated that “shared understanding” by giving prisoners news and serving as messenger boys (sometimes unwittingly) between prisoners and the outside world.

Lead:

After his release from prison in the 1990s, Mandela stated in an interview that “No, I am not particularly religious or spiritual. Let’s say I am interested in all attempts to discover the meaning and purpose of life. Religion is an important part of that exercise.”

(Words: 3,893)