Dr. K. Veeramani

President,

Dravidar Kazhagam

The Supreme Court’s historic verdict upholding OBC reservation in the all India quota of medical seats is a major achievement in the history of social justice and a significant victory for the Dravidian movement.The Supreme Court of India delivered a historic judgment on January 20, 2022, in Neil Aurelio & Ors vs Union of India and Ors, upholding the constitutional validity of 27 per cent reservation for the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in the All India Quota (AIQ) for undergraduate and postgraduate medical and dental courses (MBBS and BDS/M.S., M.D. and MDS). The seats for the AIQ are contributed every year by the States from the medical and dental colleges run by them. The AIQ concept has been in practice since 1986 as per the judgment of the Supreme Court. Every State has to contribute 15 per cent of seats in graduate and 50 per cent of seats in postgraduate courses of its medical and dental colleges.

The total number of seats pooled would provide opportunities to the students to pursue their studies in any State irrespective of their place of domicile.

In 1986, reservation for the Scheduled Castes (S.Cs) and the Scheduled Tribes (S.Ts) in education was in vogue only in certain States. But in the AIQ contributed by the States, the reservation policy for the S.Cs and the S.Ts was not adhered to. It deprived candidates from these categories from getting their share in the seats. When a petition sought reservation in the AIQ for S.Cs and S.Ts in 2007, the Supreme Court gave a direction to provide reservation for students from these categories.

There was no reservation for the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) though the OBC seats were contributed by the States to the AIQ. The States contributing seats to the AIQ have been implementing OBC reservation in the medical and dental colleges run by them. But it was not extended to the OBCs in the AIQ. No action was taken by the Union government to set this right.

In 2006, the 93rd Constitutional Amendment was effected enabling reservation for the BC/S.C./S.T. students in Central educational institutions and private institutions except those run by the minorities. The OBC reservation was extended to Central educational institutions such as the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) and Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER). The spirit behind the reservation provisions of the Constitution and the practices consequential to them were not understood by the Union government. It never tried to understand them or perhaps misunderstood them and remained reluctant. This deprived the oppressed sections of their rights.

Since the 2008-09 academic year, the Union government had been implementing reservation for OBCs in Central medical educational institutions but denied OBC reservation in the AIQ, even when the contributing States were already implementing the reservation policy in their respective States. The denial of OBC reservation in the AIQ had become routine for the Union government despite consistent demands by the States.

Tamil Nadu’s Challenge

Tamil Nadu became the forerunner in challenging the denial of reservation for OBCs in the AIQ. The Dravidar Kazhagam (D.K.), which pioneered the social justice movement, convened an ‘all party meeting’. It was resolved to file writ petitions in the court individually and seek legal remedy. Accordingly, the D.K. filed a writ petition before the Madras High Court on June 4, 2020. The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), the Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (MDMK), the Pattali Makkal Katchi (PMK), the Communist Party of India (CPI), the Communist Party of India (Marxist), and the Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi (VCK), and a few social organisations filed writ petitions in the Supreme Court, which directed them to file petitions first in the Madras High Court. Later, the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) also filed both as the ruler of the Government of Tamil Nadu and as a political party. It was argued that the Saloni Kumari case (2015), relating to OBC reservation in the AIQ, was pending in the Supreme Court and hence the Madras High Court could not deal with the petitions. It was clarified that the grounds for the Saloni Kumari case were different and that the Madras High Court might proceed with the petitions relating to OBC reservation. The court held that OBCs were entitled to reservation in the AIQ. Through an interim order dated July 27, 2020, the court directed the formation of a committee with the representation of the Union Ministry, the Medical Council of India and the Tamil Nadu government to work out, within three months, a scheme to provide reservation for the OBCs in the AIQ. The court, after the receipt of the report, decided that OBC reservation in the AIQ had to be provided from the 2021-22 academic year.

Later, the notification for admission in the AIQ was published by the Union government without mentioning the reservation for the OBCs. The DMK filed a contempt of court petition in the Madras High Court. In the meantime, writ petitions were filed in the apex court challenging the subsequent notification by the Union Ministry specifying OBC reservation in the AIQ. The DMK impleaded itself in this case. By then, the DMK had won the Assembly election, and its president M.K. Stalin assumed office as Chief Minister, in May 2021.

The Supreme Court’s latest verdict in January 2022 (supra) is that OBC reservation in the AIQ is constitutionally valid. The petitions filed in Tamil Nadu ended a long drawn legal struggle. It ensured reservation for the OBCs in the AIQ not only for Tamil Nadu but for all the States.

At every stage in the legal battle, the reluctance of the Union government led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was exposed. In every reply to the notices of the courts, it tried to specify some point or the other with the intention of deterring OBC reservation in the AIQ. The BJP’s stance is not unusual as it cannot deviate from the stand of its ideological mentor, the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh (RSS), which is against the principle of reservation for the oppressed. The untiring efforts put in by Stalin ensured success in the legal battle to secure OBC reservation in the AIQ.

Significant Verdict

The judgment of the apex court in January 2022 upholding OBC reservation in AIQ is unique. It is a landmark victory for the social justice cause of the Dravidian movement. The basis of the reservation policy and the perspective in which it has to be understood have been discussed consistently in a scientific way by the representatives of the movement quoting scholarly works on affirmative action. Providing reservation to oppressive sections was also seen as a form of discrimination by the critics of reservation. The anti reservationists used to say that discrimination in any form is contrary to the doctrine of equality and equal opportunities. Hence, the judgment specified: “Equality of opportunity admits discrimination with reason and prohibits discrimination without reason.”

It recalled and emphasised that the policy of reservation was a positive measure by quoting several judgments of the Supreme Court. It said: “….special provisions (including reservation) made for the benefit of any class are not an exception to the general principle of equality. Special provisions are a method to ameliorate the structural inequalities that exist in the society, without which, true or factual equality will remain illusory.”

Another frequent argument against the reservation policy is that ‘merit’ is the casualty. The judgment aptly explained that equality and equal opportunities are not aimed at bringing mere ‘formal equality’ but ‘substantive equality’. It argued that the binary of merit and reservation had now become superfluous once the court had recognised the principle of substantive equality. It referred to the spirit of the Constituent Assembly and the purpose for which social justice through reservation was adumbrated in the Constitution.

The Supreme Court explained that the oppressed sections have to compete with the historically privileged sections that have been endowed with ‘social and cultural capital’. The disadvantaged classes have to overcome the barriers created by these unique social capital that has accrued to the forward classes. The features of social capital such as communication skills, accent, books or academic accomplishments, which have been inherited by the privileged classes, are not available to the competing oppressed sections.

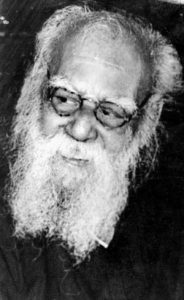

June 1970: A.N. Sattanathan handing over report of the First Tamil Nadu Backward Classes Commission to Chief Minister M. Karunanidhi in the presence of N.V. Natarajan, Minister of Labour and Backward Classes.

June 1970: A.N. Sattanathan handing over report of the First Tamil Nadu Backward Classes Commission to Chief Minister M. Karunanidhi in the presence of N.V. Natarajan, Minister of Labour and Backward Classes.

“Performance in competitive examination or admission in higher educational institutions does not require a great degree of hard work and dedication but it is necessary to understand that ‘merit’ is not solely one’s own making. The rhetoric surrounding merit obscures the way in which family, schooling, fortune and a gift of talents that the society currently values aids in one’s advancement… A contribution of family habitus, community mileages and inherited skills work to the advantage of individuals belonging to certain classes, which is then classified as ‘merit’ reproducing and reaffirming social hierarchies.” The court dismissed the repeated arguments that Articles 15(4), 15(5) and 16(4) are only enabling provisions and cannot be equated with the fundamental rights by stating: “The principles applied for interpreting Article 16 are also to be used for the interpretation of Article 15. Articles 15(4) and Article 15(5) are nothing but a restatement of the guarantee of the right of equality stipulated in Article 15(1).”

These narratives and interpretations of the Supreme Court are only illustrative and not exhaustive of its judgment and would remain as guidelines and references to decide reservation related cases in future.

It is not just a verdict but a benchmark to protect the constitutional mandate of social justice.

to be continued…

Courtsey: Frontline – February 25, 2022