Dr. K. Veeramani

President,

Dravidar Kazhagam

From the previous issue….

History of Social Justice in Tamil Nadu

Social oppressions had been prevailing for many centuries even before the arrival of British and other political conquerors. The history of social justice in Tamil Nadu is older than even the Indian constitutional history of social justice. Governmental initiatives on the dispensation of social justice date back to 1921. The First Communal G.O. was issued by the Justice Party government, which had to operate with limited power under the diarchical form of governance in the Madras province of British India. The Second Communal G.O. issued in 1922 was also not implemented and remained on paper.

During the First Ministership of Dr P. Subbarayan in 1928, which was supported by the Justice Party and by the initiative of Muthiah Mudaliar, the Minister representing Justice Party, the Third Communal G.O. got implemented for the representation of all communities, including Brahmins, in the provincial government jobs. From then onwards, the principal of communal representation got an impetus in employment and education.

The bureaucracy had earlier been the exclusive domain of a few of upper castes. The Brahminical hegemony in all spheres of life put brakes on the moves of the Justice Party to secure social justice. More than the Justice Party, it was the positive counter move of the Self Respect Movement of E.V. Ramasamy, known as Thanthai Periyar, since 1925 which kept the momentum on. Periyar joined the Congress Party in 1919 with the idea of achieving the goal of communal representation. Even when the Indian National Congress and the Justice Party were opposite political poles, Periyar, though he was a Congressman, was in favour of all the moves of the Justice Party and its socially progressive policies, including communal reservation.

A sociopolitical culture was established by Periyar’s Self Respect Movement, even while the popular support base of the Justice Party was shrinking. Every political party that assumed power in Tamil Nadu had to adhere to the principle of communal reservation as a means for social justice. The Congress Ministry that assumed office with Omandur P. Ramasamy as the Premier under provincial autonomy brought exclusive reservation for the “Backward Classes” in the Communal G.O. Because of this move and other socially progressive measures that were given legal sanctity, Omandur P. Ramasamy was ridiculed by the antisocial justice hegemony as ‘beardless Ramasamy’ (implying that was the only feature that differentiated him from Periyar). Periyar and his organisation are nonpolitical, avoiding elections and the aspiration to capture power. The land has been tuned to the principle of social justice by the D.K., the new name given by Periyar in 1944.

Setback to Communal G. O. Set Right

After the Constitution came into effect in January 1950, the Communal G.O., which was more than two decades old then, was challenged in Madras High Court by Champakam Dorairajan, a Brahmin. The challenge was that the Communal G.O. was against the equality clause enunciated in the Constitution. Without applying for an MBBS course, she had petitioned that the Communal G.O. had deprived her of admission in a medical college. The Madras High Court held that the Communal G.O. was ultra vires the Constitution. On appeal, the Supreme Court confirmed the verdict of the High Court.

Periyar revolted against these judgments stating that communal reservation was the basic right of the oppressed sections. He conducted Statewide agitations continuously. The DMK also joined the struggle under the leadership of C.N. Annadurai, popularly known as Arignar Anna. The Tamil Nadu unit of the Congress party, led by K. Kamaraj, reported the turmoil to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru paved the way for amending the Constitution for the first time. Article 15(4) was inserted in it to sustain the policy of communal reservation.

The first amendment enabled reservation not only for the OBCs, S.Cs and S.Ts in Tamil Nadu but also extended it to the rest of the States. Thus, Periyar and his movement remained as the prime force enabling the dispensation of reservation to the whole of the country after Independence.

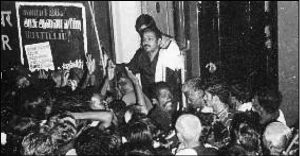

1979: Dravidar Kazhagam leader K. Veeramani at a protest against the Tamil Nadu government order introducing an income criterion for OBC reservation.

1979: Dravidar Kazhagam leader K. Veeramani at a protest against the Tamil Nadu government order introducing an income criterion for OBC reservation.

In Tamil Nadu the reservation in jobs and education was fixed at 25 per cent for the OBCs and 16 per cent for the S.Cs and the S.Ts put together during Congress rule.

In 1963, in Balaji vs State of Mysore, the apex court said the total quantum of reservation should not exceed 50 per cent. The ceiling it mentioned was only by way of obiter dictum and not an order for adherence. In 1971, the reservation was enhanced to 31 per cent for OBCs and 18 per cent for the S.Cs and the S.Ts under the DMK rule by Chief Minister Kalaignar M. Karunanidhi.

In 1979, M.G. Ramachandran as the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu introduced an economic criterion for reservation, fixing the income ceiling of Rs.9,000 a year for OBCs to get reservation. Reservation based on an economic criterion is ultra vires the Constitution, which approves backwardness only on social and educational basis. Even at the time of the First Constitutional amendment, the idea of introducing an economic criterion for reservation was deeply discussed and debated. The economic status of a person is not fixed and is ever-changing. The supporters of economic criterion in Parliament secured only five votes, whereas the opposing forces got 243 votes.

The Constitution speaks of reservation only for the socially and educationally backward classes explicitly in Articles 15(4) and 340. With respect to reservation, it is stated clearly that backwardness has to be reckoned only on social and educational basis. Parliamentary debates have clarified the spirit of Article 15(4) on social and educational backwardness and have highlighted the irrelevance an economic criterion in the matter.

Foreseeing the damage likely to be caused to OBC reservation by the ‘income ceiling’ of the Tamil Nadu State government, the D.K. started an agitation for the withdrawal of the order, and campaigned against the ‘income ceiling for OBC reservation’.

Chief Minister M.G. Ramachandran, popularly known as MGR, adamantly refused to take note of the intricacies of the concept of social justice. The D.K., the DMK, the CPI, the IUML and a few leaders of the Congress were on a continuous war path against the G.O. Many OBC associations were persuaded by the D.K. to participate in the agitation by highlighting the reservation benefits that the children from OBC communities would gain. It organised a massive agitation against the order, burnt copies of the G.O. and sent the ashes to the Tamil Nadu government secretariat as a mark of protest.

Elimination Of ‘Economic Criterion’

In the parliamentary elections held in 1980, MGR’s AIADMK faced a rout, securing only two of the 39 Lok Sabha seats in Tamil Nadu. The Chief Minister realised that something had gone wrong. His senior party colleagues pointed out that the reason for the defeat was his G.O., which went against the policy of communal reservation, the fundamental fabric of Tamil Nadu.

MGR immediately convened an all party meeting to discuss the subject. The D.K. had an opportunity to participate in it and explain the intricacies of the issue. It explained why the G.O. fixing an income ceiling for OBC reservation was meaningless. For instance, if an OBC government servant earns in a year less than Rs.9,000, his children would be eligible to get reservation benefits. If the same person is transferred to Chennai city, he would earn more through city allowances. His total annual income would then exceed Rs.9,000, depriving his children of reservation benefits. The flexible nature of economic status is ultra vires the Constitution and hence, was not included in the formulation of reservation policy.

Enhancement Exceeding Fifty Per Cent

MGR was convinced, and a few days later the G.O. on income ceiling was withdrawn. Besides, MGR enhanced the OBC reservation from 31 per cent to 50 per cent. The total reservation in Tamil Nadu became 68 per cent (50 per cent for OBCs plus 18 per cent for S.Cs and S.Ts). With the exclusive 1 per cent for the S.Ts, the total percentage rose to 69 per cent in 1989.

It was a historic turning point in the history of social justice. The hesitation on the part of the rulers to enhance the reservation above 50 per cent is unwarranted. The impediment was removed by enhancing the reservation for OBCs to 50 per cent in Tamil Nadu. The State, with the ideological strength of Periyar’s movement, had shown the way to the rest of the States. However, some States have not enhanced the limit beyond 50 per cent because of a lack of awareness about its significance or hesitation to take such a bold step.

The Mandal Milestone

The implementation of the Mandal Commission recommendation of 27 per cent reservation for OBCs in Union government jobs and its upholding by the apex court was the next milestone on the path of social justice.

The Mandal Commission, constituted as per Article 340 during the Janata Party rule in 1979, presented its report to the Congress government in 1980. The recommendations remained on paper without any followup. Continuous demand was made by the social justice forces for tabling the report in Parliament and for accepting its recommendations. The D.K. conducted 16 agitations and held 42 conferences at the all India level to bring the Mandal recommendations to the limelight.

In 1990, Prime Minister V.P. Singh implemented one of the recommendations, that is, 27 per cent reservation for OBCs in the jobs of Union government and its undertakings. Karunanidhi, then Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, played a major role in having the Mandal report implemented. As usual, the Office Memorandum announcing its implementation was challenged in the apex court. Ultimately, the constitutional validity of reservation for OBCs was upheld in Indra Sawhney vs Union of India. But exceeding the scope of the legal challenge, the apex court pronounced that the total reservation must not exceed 50 per cent. The 50 per cent ceiling on reservation is nowhere mentioned in the Constitution. The total reservation of 69 per cent in Tamil Nadu faced a threat.

At this juncture, J. Jayalalithaa was the Tamil Nadu Chief Minister. The D.K. suggested the way out to protect 69 per cent reservation.

The D.K.’s advocacy was: Article 31(C) provides power to the States to legislate and protect 69 per cent reservation. An exclusive legislation may be enacted by getting the assent of the President of India. In order to protect the proposed Act, with retrospective effect it may be placed in the Ninth Schedule as per Article 31(B), and 31(C) of the Constitution and remain immune to judicial review. Such placement of the Act requires a Constitutional Amendment to be made by Parliament.

The D.K.’s suggestion was accepted by Jayalalithaa. The State Legislative Assembly was exclusively convened for the purpose and the Bill was passed unanimously by all the legislature parties. A delegation of parties led by the Chief Minister and the author as the D.K. general secretary met Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao to apprise him of the significance of the Bill. His intervention to get the President’s assent for the Bill was sought. The Bill turned Act was placed in the Ninth Schedule through the 76th Constitutional Amendment in 1994. All the parties in Parliament unanimously accepted the move of Tamil Nadu. Constitutional protection for 69 per cent reservation in Tamil Nadu became a reality. The D.K., and Tamil Nadu, the land of Periyar, ensured the enactment of an exclusive legislation seeking to implement the reservation policy with retrospective effect and due constitutional amendment.

This towering achievement took place in 1994, but its significance was not properly understood in political circles. Since 1980 through G.Os and from 1994 through an exclusive enactment, 69 per cent reservation has been under implementation in Tamil Nadu. Many States which have realised the need to enhance total reservation beyond 50 per cent in their respective States consider the Tamil Nadu Act as a model. This includes a few States ruled by the BJP and its allies.

Courtesy: Frontline – February 25, 2022