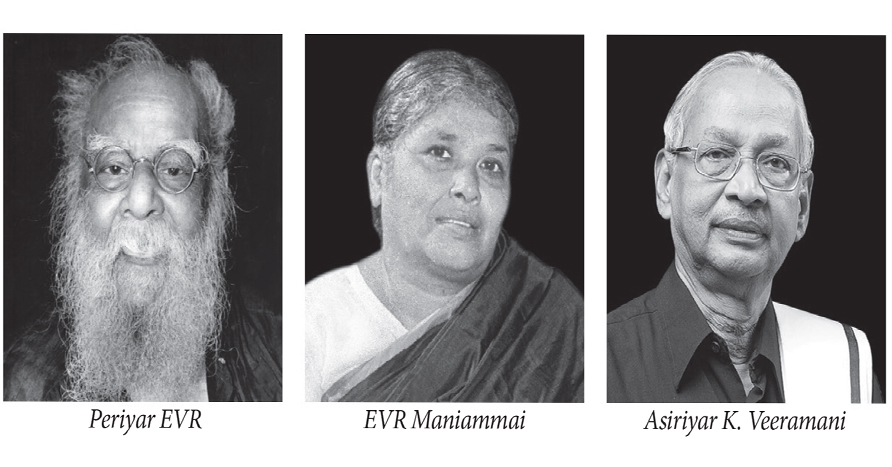

Mr. Veeramani, as Periyar’s philosophical heir, travelled about the state, making speeches, and conducting Periyar Self-Respect marriages. In Tamil Nadu, where many people couldn’t read and write, speeches, were important. People enjoyed speeches, the sound of words…

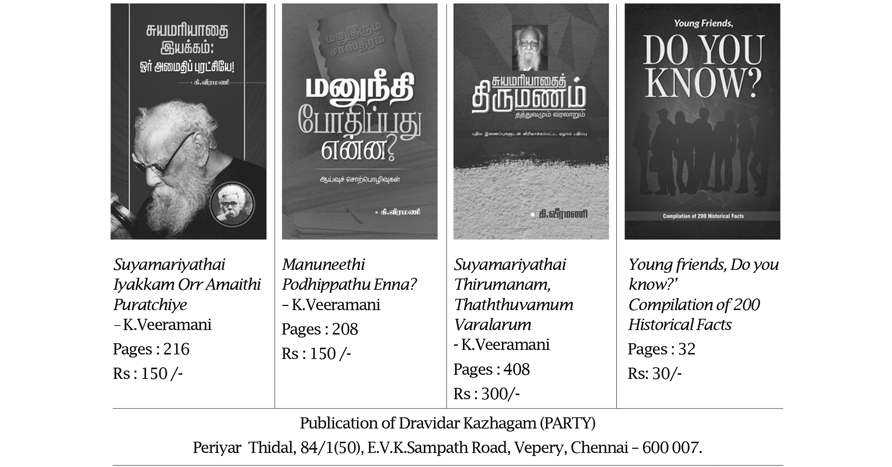

Mr Veeramani said he could speak for up to two hours at a time, if there was the need. As for the Self-Respect marriages, he did only about eight or 10 a month, about 120 to 150 a year. Not many; but the rationalists Mr. Veeramani said, were only a ‘microscopic’ element in the state. He didn’t think it lessened the importance of his work. This was to preserve as much of Periyar’s message as possible. So he looked after the relics – the bed, all the various gifts to Periyar; he explained the iconography of the 33 paintings in the room, showing the stations of Periyar’s long life; he published pamphlets; and he led visitors round the grave, reading out the more famous sayings of Periyar’s that were carved in grey granite around the grave, Without this work of his over the years, Mr Veeramani said, Periyar’s message would have been distorted.

When he was about ten or so, Mr Veeramani acted in a school play…

Mr Dravidamani was so impressed by the boy’s talents that he began writing speeches on the Self-Respect theme for the boy to deliver at public meetings. In 1944 in Cuddalore there was a Dravidian Conference. Periyar came to that. There also came a famous atheist Tamil poet who was a disciple of Periyar’s. The poet’s name was Bharathidasamn. He was forty-seven, originally of the weaver caste, and he lived in great poverty in the town of Pondicherry (then a French colonial enclave in British India). He was thought of as the Shelley and the Whitman of the movement. There was a poem of Bharathidasan’s that was regularly quoted in Self-Respect speeches. Mr. Veeamani gave me this translation the poem:

The world is still in darkness.

Even people who believe in caste are allowed to live.

The persons who frighten people by religion are still thriving.

When will all this trickery come to an end?

Unless and until this kind of trickery comes to an end,

Freedom and liberty are to be equated with evil only.

In 1949, five years after the Cuddalore conference, there was a split in the movement. It was caused by Periyar’s decision, at the age of seventy, to marry for the second time.

This was the story Mr Veeramani told me, and he was anxious for me to understand why Periyar had married at this late age. Periyar had accumulated a lot of property. He didn’t want this property to pass to his relatives. He wanted it to be used for the movement, and his thought that this could be best done by leaving it to his secretary-nurse. Under Hindu law, however, he could make her his legal heir only by marrying her.

Not everyone understood the motives, and an important section of the movement broke away to form their own group. Mr Veeramani, however, at this stage a fifteen-year-old rationalist, remained loyal to Periyar. He remained loyal when he went to the university; he remained loyal when he began to study law. And then, while he was still doing his law studies, something important happened.

In 1957 Periyar was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment for burning the Indian Constitution.

When Periyar came out of jail, he sent for Mr Veeramani. Periyar was in the town of Tiruchy. Mr Veeramani went there immediately.

Periyar said to him, ‘What about your future? Are you going to get married?’

It was a surprising question, because Periyar was against early marriages; he thought they worked against the uplift of non-brahmins. Mr Veeramani at this time was twenty-five, and he still had more than a year to do at Madras Law College.

Mr Veeramani said, ‘Sir, I don’t think marriage is a necessity at this stage. I don’t have my own economic independence, and I would like to give my most to the party.’

Periyar said, ‘But it’s only in the interests of the party that I’m suggesting marriage to you.’

The girl or young woman whom Periyar wanted Mr Veeramani to marry was the eldest daughter of a couple for whom, in 1933, Periyar had performed a Self-Respect marriage. That Self-Respect marriage had become politically famous, because in 1952 its validity had been challenged in the courts. But – sentiment apart – Periyar’s real reason for wanting Mr Veeramani to marry the daughter of that couple was that the family was well-to-do, the father belonging to a merchant community, the mother coming from a landowning family; and marriage to the daughter would enable Mr Veeramani to work full time for the movement.

When Mr Veeramani understood this, he said to Periyar, ‘If it is in the largest interests of the party, I will obey your command.’

Mrs Maniammai then went to Mr Veeramani’s parents to give them the news that their son was going to get married, and after this she took Mr. Veeramani to the girl’s house in Tiruannamalai. They went by train and bus and finally arrived at the farm-house where the girl and her mother were staying. There was a lot of fertile land attached to the farm-house – rice fields and groundnut fields. After the usual preliminaries the girl came out and served some food (a curious remnant of old ritual), and then went back inside. But, in fact, she knew Mr Veeramani well, from his appearances in public meetings.

Six months later the marriage took place. Periyar and Mrs Maniammai sent out the invitations in their own names, so the wedding gathering was like another Dravidian conference. The wedding itself took place on a Sunday afternoon at five. The time was chosen quite deliberately, because orthodox Hindus considered it an especially inauspicious time. The atheist poet Bharathidasan, the Whitman-like figure of the movement, read out a poem he had composed for the occasion.

There was a curious sequel: in his final law examination, Mr Veeramani found himself having to answer a question about the 1933 Self-Respect marriage of his in-laws.

The marriage had worked out as Periyar had hoped. Mr Veeramani had been free to do his work for the Dravidar Kazagham, the Dravidian Movement, and had kept Periyar’s name and message alive. And now, after all the ups and downs of the last 30 years, Periyar’s more-than-life-size portrait was to be seen in many places in Madras, and Mr Veeramani, keeper of the flame, moved through Madras like a hero.

Until this trip to Madras, Periyar had been barely a name to me; and I had never heard of Mr Veeramani. Bur for 40 years Mr Veeramani had been at the centre of an immense local revolution, which, with all the economic and intellectual growth that had come to independent India, had taken on the characteristics of a little war; and so far Mr Veeramani had been on the winning side.