Salem Dharaneedharan

Dravidian Professionals’ Forum

Across the world, education, instead of becoming a mechanism for mobility has become a fortress of privilege. More often in India we hear this debate on how affirmative action thwarts meritocracy or why exams like NEET fosters meritocracy and helps the country produce better doctors. These are narrow views and opinions stem from lack of understanding of the term “merit”. The idea of merit is abstract, or can be even termed treacherous. Naively in many quarters “merit” is simply considered to be performance in a competitive exam. However, this view remains oblivious to many external factors such as caste based cleavages, parental exposure, schools attended, living environment or other negative influences like childhood abuse and neglect among many other similar factors. A child born to a dalit family in a rural village will have 10x limited exposure and resources compared to someone who is born in Delhi to an upper middle class family. The former is most likely to attend a school with poor infrastructure, working part time with his parents, while the latter is enrolled in one of Delhi’s best schools, and his parents have already decided on his future ambitions-giving him an early mover advantage. How could ability or talent be measured in such a scenario? Would it not be unjust if both these kids are made to face the same exam and their application is decided solely based on the results of this exam? So linking the future of millions of children or adolescents, based on performance of a single competitive exam, such as NEET, which is trainable, is unfair and unjust. And, this simply perpetuates inequality, attenuating existing cleavages.

All forms of selection criteria have some form of discrepancy; Pure merit as such is a myth and is an utopian concept. But, what policymakers could do is devise a methodology that minimises these discrepancies and inherent biases. This is what DMK Government under Kalaignar did by abolishing entrance exams for admission to medical exams and introducing Samacheer Kalvi – A common, watered down syllabus for all students of TN. Research points to the fact that a simpler curriculum, levels the playing field to a certain extent.

Though only several research studies have been undertaken on NEET, there has been a plethora of research that has been undertaken across the world, on how competitive exams are antithesis to the principle of merit. As per Justice AK Rajan, committee report, in 2010, 80.2 per cent of English medium-educated students and 19.79 per cent of Tamil medium students were admitted to various medical colleges in Tamil Nadu. But in 2017 after NEET was introduced, 98.41 per cent of students who got admissions were English-medium educated. Only 1.6 per cent of students who secured seats were Tamil-medium educated.

For example, data from pre- and post-NEET years show that the exam heavily favours non-first generation graduates or FGs. In 2010-2011, the percentage of FG candidates securing medical seats was 24.61 per cent (non-FGGs securing admissions stood at 75 per cent).But in 2017, after NEET, this percentage dropped drastically to 14.46 per cent of FGG candidates securing medical seats, leaving the rest (a huge chunk of 85.54 per cent) to non-FGG candidates. Similarly, most students who pass NEET seem to be from CBSE background – again most CBSE schools are expensive, and at the same too much insistence on CBSE schools might force our kids to learn more propaganda that is being forced into NCERT curricula by the incumbent BJP Government.

A study by The Washington Times and Bloomberg showcases that chances of someone coming from a rich family (top 1 per cent), one’s chances of attending an Ivy League school are 77 times greater than if one comes from a poor family (bottom 20 percent).

The primary reason for the above mentioned discrepancy lies in the primary fact, as stated above, that these entrance exams are trainable, none of the entrance exams or tests are designed to test the inherent intelligence of a person. The positive test results largely depend on the number of hours spent and quality of teaching received. Those from affluent backgrounds would be able to afford their children special private tuitions, which in India costs more than INR 1 LAKH a year. An IIT study in 2005, identified that 95 per cent of those who cleared IITs had attended private coaching classes, out of which 75 per cent were from urban areas. Shockingly until a decade ago 1/6th of IIT admits originated from a single coaching institute, Bansal classes, based out of Kota. Some of these institutes charge somewhere between INR 1 LAKH TO 2 LAKH a year. A sum unaffordable to the majority of Indians, which is why just 2.86 per cent of the students who get admitted into IITs are from poor/rural, uneducated families. The author, who himself was a successful candidate at AIEEE, says 70 per cent of the students who joined NIT Trichy, from Tamil Nadu, after introduction of AIEEE, around mid 2000s, were from Chennai, specifically from a few select schools.

According to research by Elaine M. Allens worth, Kallie Clark of University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, School marks are affected to a much lesser extent by cleavages based on income and race. The research also identifies that school marks have turned out to be a better predictor of performance in the University . (This was shown to have a more profound impact on students from Poorer or racially marginalised backgrounds). In fact, for two students with the same SAT score, their high school GPA turned out to be a better predictor of success in school. If two students with same test scores are compared, the students with higher school marks had performed better in college and in real life thereafter. These facts are consistent with the findings of the committee set up by Government of Tamil Nadu. On the same lines a RTI observed 90 per cent fall in Tamil-medium students in govt medical colleges after introduction of NEET.

Another research by Oswell, author of outliers, concludes, based on long term experiment undertaken at University of Michigan, that even if marginalised students, say from poorer Black neighbourhoods, were admitted based on affirmative action, despite much poorer performance in comparison to their white colleagues, though their college grades remained lower than white colleagues, their professional achievement in medium term matched with that of white colleagues. The reason for this is because, students who manage to succeed- such as getting admit at a top university or a medical background, in-spite of their disadvantaged backgrounds, are found to be more aspirational, determined and tend to persevere more to achieve success. Let us take the case of Anitha, she was born to a very poor, dalit family, in rural Tamil Nadu, she lost her mother when she was a child, her father was a manual laborer, in-spite of all the inherent biases, she managed to score 1176 out of 1200 in her school exams, putting her in the top 0.3 per cent ile. If there wasn’t any NEET, based on her school marks, she would have gone on to study at one of Tamil Nadu’s best medical colleges, becoming first doctor from her entire community. Was it her lack of ability that stopped Anitha from clearing the NEET or was it the paucity of time or lack of exposure and resources? Of-course, it was lack of time, lack of exposure and resources. If she was given an opportunity to pursue her dream, she would have gone on to perform better than even the candidate who stood first in the NEET exam, with the help of coaching institute. Now because of NEET we not just failed Anitha, but failed the aspiration of an entire community. NEET related suicides are not due anxiety , but, rather due to loss of aspiration and hope. This is why most of the NEET victims are from rural and marginalised backgrounds.

Many top ranking Universities across the world are relying less and less on entrance exams. Even the world famous University of California has scrapped entrance exams for admission to its degree program, in the name of equal access. Similarly,France’s elite Sciences Po, which has produced 90 per cent of French Presidents, nearly diplomats of French republic and 4 past heads of IMF has rescinded the entrance exam on the basis of positive discrimination and now relies only on school marks for admission. ENA and Sciences Po, together in France, are as important, if not any lesser, than Lal Bahadur Shastri institute of public administration, which trains the Indian Administrative Service officers, scraped the entrance exams for admission, based on decades long study. So Modi Govts’ decision to force NEET on students, is based on ill founded research and does not do anything to Improve quality.

If evidence from results of other entrance exams are to go by, continuation of NEET will disproportionately produce more doctors from urban cities than that was traditionally produced in Tamil Nadu, leading to lack of doctors in rural areas. Moreover, NEET also destroys the aspirations of 1000s of rural and marginalised students of Tamil Nadu.

NEET against Federalism

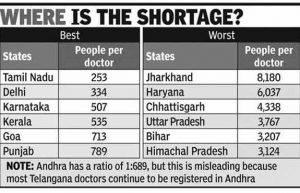

Due to extraordinary investments made by successive Dravidian governments in Tamil Nadu, in the ranking of Indian states for health care outcomes, Tamil Nadu always ranks within the top 3. Tamil Nadu not only has the highest number of doctor per population, but also has the best spatial distribution of doctors, which was achieved by interventions such as abolition of entrance exams, introduction of caste based / horizontal reservations (reservation for rural / govt school students) and opening up of Medical universities all across Tamil Nadu. In-fact, Chennai, capital of Tamil Nadu serves as the hub for medical tourism in India. Why should a State that has made enviable progress in health care be forced by Union government to deviate from its successful developmental model. Should it not be that, Tamil Nadu be made as a best case example for the rest of India, and the Union Government recommends the Tamil Nadu model for other states to emulate. India again is a country as diverse as countries of European Union; and level of development varies between States greatly, Tamil Nadu for example has 32 times more doctor per people than Jharkhand, when such discrepancies exist among states, how can Union Government aim to have a single admission procedure for such a diverse country.

With health being a State subject, and education being in Concurrent List, it is only fair that the President of India, appreciates the law passed by the Government of Tamil Nadu in the Assembly and gives his assent to the same. Any further continuation of NEET in Tamil Nadu is a Travesty of Justice and an insult to the concept of federalism.