Madhavan K. Palat

It irritated him that the focus of elections was always himself rather than policies and programmes Jawaharlal Nehru was a committed democrat; but he was tortured by doubt and often frustrated by the democracy over which he presided with such aplomb.

Drawing on his wide reading and experience in the Independence movement, he had arrived at an exalted notion of democratic procedure as requiring among other things leaders and parties placing choices before the people to discuss issues threadbare in public. But he was appalled to discover that nothing of the kind happened. In 1951, he complained that political parties were busy peddling lies and deceit; in 1957, that “fundamental issues are seldom mentioned”; and by 1962, that “people seem to go mad the moment elections are announced”.

Elections seemed to bring out the worst rather than the best in people. He grumbled with tedious regularity to a host of confidantes, be it Krishna Menon, Louis Mountbatten, Bidhan Roy, Rajagopalachari, or Vijayalakshmi Pandit. He wrote in despair to Govind Ballabh Pant, Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, “This elections business is making me lose my faith in Indian humanity”. He confessed to being “depressed”, as candidates ceaselessly calumniated each other and engaged in bitter internecine strife.

There seemed to be “a ceaseless round of elections” and the slush funds and sleaze distressed him greatly. As the third general election approached, he moaned that “democracy is full of defects and elections vitiate the atmosphere”, and he was reduced to citing Winston Churchill. He reproduced this theme in virtually every speech during the campaign, denouncing elections on one occasion as “madness”, but with typical self-deprecation, adding that his joining the Congress in 1912 and the freedom struggle itself was all “madness”.

Ideology and dogma

He even likened democracy to religion, although organised religion, its priesthoods and dogmas were all anathema to him. He informed the World Council of Churches in Delhi in 1961 that both democratic and religious leaders faced the unenviable choice between adhering to principle and making concessions to their following. Unwavering rectitude entailed isolation and saintly martyrdom; but striking deals could lead to corruption and betrayal. He was intrigued that such a comparison was possible. It reveals his angst about democratic mass parties being akin to religious bodies and party ideology becoming dogma. He had called Gandhi a saint who did not falter, and before him there were Muhammad, Jesus, and most of all Buddha, all in the same league, revolutionary leaders who were unflinching and yet found followers in such abundance down the centuries. These were leaders of the quality he esteemed. He placed himself below the pinnacle, at the level of the compromise, and agonised over his unhappy fate or choice.

He was severely disappointed by the electoral process, yet had great faith in the people and had no doubts about universal suffrage. But, he spoke to them as a missionary converting the heathen, a communist imparting consciousness, or a teacher instructing wayward pupils. Democracy, he sermonised, entailed accepting the results of elections with good grace, to criticise without abusing, to debate without giving or taking offence, to stand for principle rather than indulge in prejudice, whim, and personality, and much else of that order. By the second general election in 1957, he developed a new theme of elections as educational: “I would like to call this general election some kind of a university for 37 crore people in India.” He admitted to functioning like a schoolmaster; and during the third general election, he even apologised to the public “for lecturing like a professor”.

If he was not the professor, he was certainly vice-chancellor to this vast university dispensing education of such quality to the masses. He left the bread and butter questions to lesser mortals like the candidates and held forth on weightier and global concerns. The people had been summoned to the task of nation-building, “so they must understand the issues and be prepared to shoulder the burdens.”

He was also teaching the difference between parliamentarism and satyagraha. Like Narendra Deva and others, he saw that the independence movement had nurtured the spirit and tradition of agitation, not of debate. Negotiations between the national and colonial leaderships were acceptable, for they were designed to arrive at a settlement to extinguish an illegitimate colonialism; parliamentary debate on the other hand was premised on the legitimacy of the opposing parties and their moral and constitutional right to form governments. Nehru never tired of clarifying that Gandhian forms of direct action were now unconscionable as India was blessed with her own rightful elections and parliament. But he suspected that the Indian public was wedded to agitation and considered governments dodgy.

Perversely faithful

Ironically, he himself had not learnt the lesson well enough, and was party, however reluctantly, to the dismissal of the elected Communist government of Kerala in 1959 following agitations by opposition parties and groups. He had hoped to nudge the people toward parliamentary procedure by undoing what the national movement had habituated them to, and while Indian politics has remained perversely faithful to Gandhi, but without his discipline, he himself compromised.

Nehru’s other fear was about democracy breeding an “elective aristocracy”. Voters elected leaders whom they did not know, with whom they did not and could not communicate, and over whom they had no control after the elections. Such leaders engaged in a permanent competition for the vote and congealed into a crust of professional politicians who dealt in votes in the manner of businessmen dealing in oil, as a cynical member of the tribe once famously remarked. They struck deals between themselves and presented such decisions to the public through the ritual of voting in Parliament. A yawning gulf stretched between them and the electorate, and there seemed to be no reliable institutional means of closing that gap. It was becoming an electoral democracy with the disempowered citizen, Jayaprakash Narayan warned.

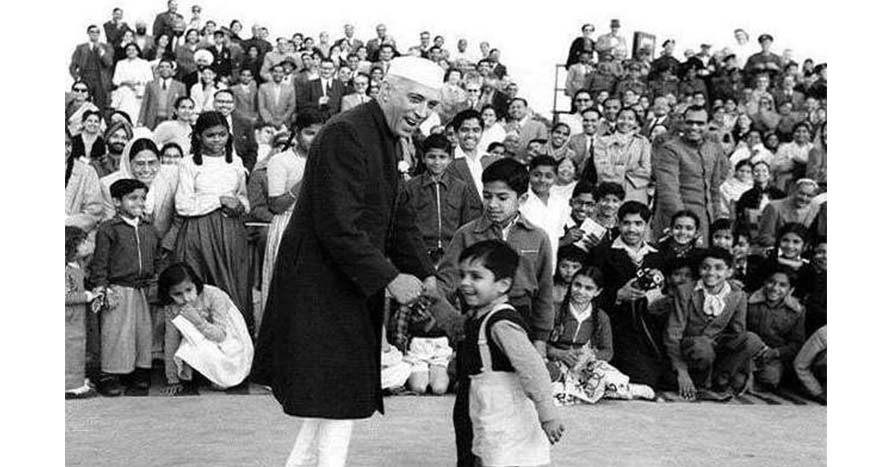

What then did Nehru find positive about democracy? It was the activism of the masses and his direct contact with them. In late January 1952, he described his state of exaltation after his election tours, his “feeling of adventure and excitement”, an inexhaustible energy flowing through his system, and the heightened “emotional awareness” on both sides. He admitted to “a special bond between the people and me which I cannot describe or write about”, and “…when I speak it is not as Jawaharlal, but I speak in the voice of the millions of Indians.” Had he not been so rational and agnostic, he would have taken to believing in mystical communion between himself and the people.

Democratic dictatorship

It irritated him that he himself rather than policies and programmes was the focus of the election since he alone blocked his rivals’ chances of success. Understandable, he mused, since “without me in the Congress, there would have been no stable government in any State or in the Centre”. But he commended the Communists for attending to programmes and issues like food supplies rather than to personalities. Democracy threatened to make of him an elected dictator; and with greater justification than Robert Clive, he could well have declared, “I stand astonished at my own moderation.”

Some of his loudest critics contributed to the potential cult despite themselves. Jayaprakash Narayan discerned in Nehru preternatural ideological prowess. He commented on the Congress’s Avadi resolution of 1955 on the socialistic pattern of society: “There is no other instance in the history of the world of a single person changing overnight the ideology of a party and declaring that from then on its ideology would be Socialism.” He denounced it as “democratic dictatorship”, but he also recommended in 1958 that Nehru should retire, choose a substitute, and guide the nation from outside, and return when needed. He transfigured Nehru into a Mahatma, a presiding deity who could descend periodically into the profane world of Indian politics, cleanse it of evil and corruption, and resume his place in the heavens. Nehru wisely declined the proffered crown of supreme moral authority.

Granville Austin, that most erudite historian of the Constitution, has observed that Nehru himself was the single greatest obstacle to arbitrary rule, and he cited Nehru’s implacable critic, N.G. Ranga, in support. Almost in spite of himself and every opportunity thrown his way, Nehru has bequeathed to us a democratic ideal instead of a fascist burden. We cannot be too grateful.

Courtesy: ‘The Hindu’