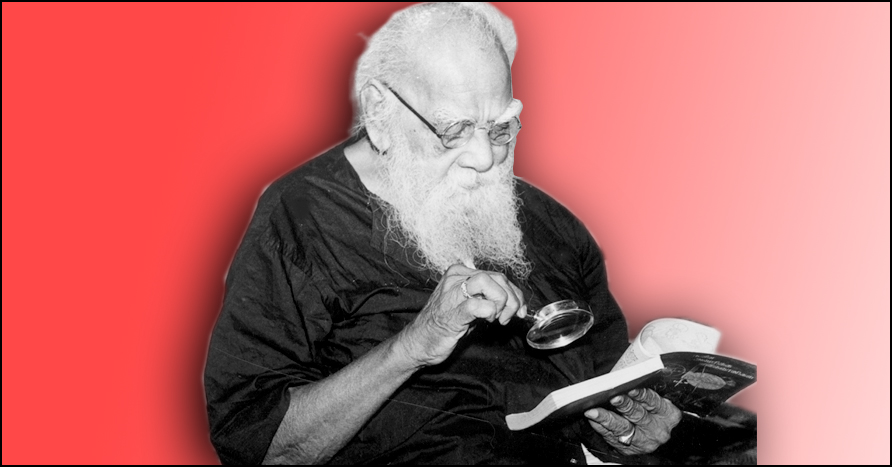

R. Vijaya Sankar

Editor – Frontline

In the early 1930s, Periyar spent about three months in the Soviet Union while on a trip to Europe.

One of the earliest propagandists of socialism from the non-Left camp in southern India was the patriarch of the Dravidian movement, Periyar E.V.R., a staunch nationalist and Gandhian who literally walked out of the Congress protesting against its refusal to accept his demand for communal representation and many of its leaders’ socially reactionary outlook. This radical phase of Periyar’s political trajectory began with his formal association with the leaders of the nascent trade union movement in the Madras Presidency during a railway workers’ strike in Nagapattinam in 1925. Periyar was arrested for his support to the strike. He found an ally in M. Singaravelu, one of the founders of the Communist movement in this part of the country, to take forward his movement for social justice. Singaravelu wrote many articles in Kudi Arasu, a paper founded by Periyar to propagate his ideas of social justice and self-respect.

On October 4, 1931, Kudi Arasu carried an editorial introducing the Communist Manifesto and serialised its Tamil version translated by P. Jeevanandham, another Communist veteran and a member of the Self-Respect Movement (which was founded by S. Ramanathan in 1925). The editorial records that although the socialist sentiment emerged in the world many centuries ago, it took the shape of a manifesto in 1847 and attained concrete political form in Russia in 1917.

“We’ve got hold of a report relating to this. Although the Germans were the first to feel this socialist sentiment, a conference of socialists was held in London, and an agitation for socialism happened in France, it so happened that it was Russia which tried to bring it into practice. This might have come as a surprise to some people but there is no reason for such surprise…. Socialism has been brought into practice first time in Russia because the tsar’s rule was the most tyrannical of all the governments in the world then. Going by this logic, it was in India, rather than Russia, that socialism must have come into practice. However, there have been many conspiracies in India to prevent that eventuality. The conspirators have very carefully kept the people of India in a barbaric state by blocking their ways of acquiring education, knowledge, worldly wisdom and self-respect and, in the name of God and religion, instilling in them the idea that it was God’s will that they remain slaves and attain moksha.”

What stands between the people of India and revolutionary consciousness? The editorial explains:

“However, because it [socialist sentiment] has occurred in other parts of the world, it is raising its head in India also. There is an important factor that hampers the spread of the socialist sentiment in India, a factor that does not exist in other parts of the world. In other countries, the crucial contradiction is between the capitalist (the rich) and his worker (the poor). However, in India, the concept of upper caste and lower caste is primary and dominant and that contradiction serves as a fort that protects the rich-poor divide. It is because of the twin opposition that the socialist sentiment has not acquired strength in India.”

About two months after the publication of this editorial and the serialisation of the Communist Manifesto in Kudi Arasu, Periyar embarked on a journey to Europe with Ramanathan and R. Ramu, a young relative. During the journey that began on December 13, 1931, from Madras harbour and ended in November 7, 1932, Periyar spent about three months in the Soviet Union. His conversion to socialism was complete.

Much later, in 1972, Periyar recalled the achievements of socialism in the Soviet Union in an article in Unmai, a Dravidar Kazhagam publication. He made the following observations:

∙ “In Russia, there is no compulsion for parents to bring up their children. The government takes up the responsibility. Here, if we ask ‘why do you need a child’, he says, ‘to light my funeral pyre and to perform the last rites after my death… to protect us and feed us in our old age… to inherit my property’.”

“It is not like this in Russia. As long as he is physically strong he toils to earn a living. In his old age, the government provides food and other facilities. Since an individual has no right to private property, there is no need to have a child to inherit property.”

∙ “In the socialist country, there is no God, no religion or no belief in shastras. No human being is considered high or low… no superior worker or inferior worker. All are equal. The salaries and comforts of life are equal; only the jobs are different. If he gets a higher job, he knows it means higher responsibility. So, production increases.”

∙ “There each person’s hours of work and quantum of work are fixed. Like our workers, they do not run away at the end of the fixed time. He voluntarily works for some more time. The management takes note of the extra work and honours them at the end of the month or the year. There they expect this honour, not extra money. There is absolutely no cheating or robbery.”

∙ “There is abundant honesty among the people. As I have told you earlier, people there live without worries. That is why Russia has thousands of people aged 100 or 120.”

Periyar and Singaravelu chalked out a new programme for the Self-Respect Movement, which was adopted at a conference in Erode despite stiff opposition from a section of leaders, including Ramanathan. The “Erode Programme” demanded, among other things, complete independence from the British and other forms of capitalist governments, cancellation of national debts; public ownership of all agricultural and forest land, waterbodies, railways, banks, shipping and other modes of transport; cancellation of the debts of workers and peasants; bringing all native Indian states into a federation to be ruled by workers and peasants. The adoption of the programme marked the birth of the Samadharma Party of South India as the political wing of the Self-Respect Movement.

At a Self-Respect Movement’s conference in Tiruppur in April 1933, Periyar explained his new political understanding. To quote E.Sa. Visswanathan (The Political Career of E.V. Ramasami Naicker, Ravi & Vasanth Publishers, Madras, 1983):

“He said that the movement had all along been indulging in mere rhetoric against popular Hinduism and the ruses of Brahmans without paying any attention to the economic and political interests of non-Brahman masses. They could improve their social status only by promoting their economic condition and not merely by rejecting Brahmans’ ritual status. The economic interests of non-Brahmans could be improved not by the present democratic system of government dominated by capitalists, but by a socialist government formed by workers themselves.”

With this new outlook, according to Visswanathan, the two wings of the Self-Respect Movement translated and published the biographies of Marx and Lenin, and the first Five-Year Plan document of the Soviet Union; launched weeklies such as Puratchi (revolution), Paguttharivu (rational thought), Samadharmam (socialism) and Vedigundu (bomb); and organised public meetings on May Day. Periyar himself addressed about 50 May Day meetings, and toured Tamil districts denouncing private property and advocating the establishment of the Soviet form of government.

This set alarm bells ringing in the corridors of power. The British government could accommodate a social justice crusader but could not tolerate his turning into a revolutionary spreading the word of socialism. It stepped in when Periyar wrote an editorial in Kudi Arasu on the need to overthrow the government. Charging him with sedition, it sentenced him to nine months in jail and imposed a fine of Rs.3,000 on him.

The British government banned the Communist Party of India in 1934.

In the face of the British repression, the opposition to his radical programme from a section of his Self-Respect Movement colleagues who feared that the movement would lose the gains it had made in the first decade of its existence, and the Congress riding the crest of a nationalist wave in which he saw the resurgence of Brahminism, Periyar had to make a difficult choice. “When I realised that the government was determined to repress the Self-Respect Movement and that our movement had already suffered [as a consequence of the government’s surveillance and interference] and when I saw that even the Congress had retreated into indirect action, not able to countenance government repression… I decided to put a halt to socialist propaganda by the Self-Respecters…”, he wrote in Kudi Arasu.

The choice Periyar made then changed the course of history and politics in Tamil Nadu.

Courtesy: Frontline