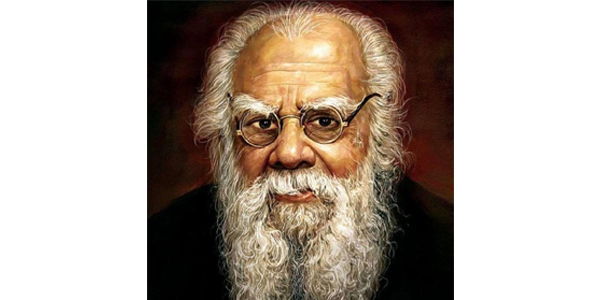

The sudra question is a complicated one in Indian sociology, history and politics, but it had an impact on a significant period of the Dravidian movement. Periyar E.V. Ramasamy referred to the non-Brahmin castes of South India, who did not belong to the ‘untouchable’ communities, as sudras, the lowest varna in the Hindu social order. He used the inferiorized identity of ‘sudra’ not in assertion or pride, but as a social critique of brahminism. Acknowledging the existence of multiple jatis within the sudra varna, Periyar criticized their notions of hierarchy towards each other and especially towards the Dalits. He sought to consistently remind the sudras of their place within brahminism and the need to challenge caste as a system. This paper discusses how Periyar’s ‘sudra critique’ also contained within it an alternative approach to the nation-state.

When Kancha Ilaiah published his controversial book Why I am not a Hindu (1996), he subtitled it A Sudra Critique of Hindutva Philosophy, Culture and Political Economy. Ilaiah’s output in contributing to this “critique” has been quite prolific, the most recent being the co-edited volume The Shudras: Visions for a New Path (2021). But why use a Sudra critique when Ilaiah himself identifies that the concept of ‘Sudra’ is derogatory in the Brahminical vocabulary and that “it does not communicate a feeling of self-respect and political assertion” (Ilaiah 1996)? For political purposes, Ilaiah (1996: ix) prefers the term Dalit Bahujan, building on the concept introduced by Kanshi Ram, the founder of the Bahujan Samaj Party, and defines it as ‘people and castes who form the exploited and suppressed majority.’ The ‘Sudra’ concept is used as a critique of Brahminical ideals so as to arrive at a Dalit Bahujan politics. Ilaiah frequently cites Jotirao Phule and B R Ambedkar as being crucial to the development of his Sudra critique. He also refers to Periyar E V Ramasamy (Periyar hereafter) as an important Dalit Bahujan thinker. Indeed, as far as Tamil Nadu is concerned, it is Periyar who made a ‘Sudra critique’ of Brahminism popular and acceptable in the public sphere, cementing what is commonly known as Dravidian politics.

It is worth considering some empirical realities before we proceed further. It is now commonly understood in the academia that it is jati and not varna that is operating in practice in Indian society at large. This, however, does not make the varna model irrelevant. While there are thousands of jati groups and it is at this level that ‘caste injunctions on marriage, occupation and social relations are conducted’ these castes nevertheless ‘draw their ideological rationale of purity-pollution, endogamy, commensality, and so forth, from the varna model’ (Gupta 2000: 199). Many jatis claim affiliation to a particular varna. Also, jatis that are placed lower in the varna order lay claim to a higher varna status. For instance, Jats in Punjab and Reddys in Andhra Pradesh are supposed to be Sudras, but they lay claim to be the Kshatriya varna—Ilaiah calls them neo-Kshatriyas. This idea of Sudras as fallen warrior communities was proposed much earlier by Phule and Ambedkar. In Ambedkar’s hypothesis, the Sudras were an Aryan community who were fallen kshatriyas owing to a long conflict with the Brahmins (Ambedkar 1990: 11-12). His predecessor Phule saw the Sudras as persecuted kshatriyas. According to him, the Brahmins sustained their domination by dividing the oppressed castes and deepening the antagonisms between them and further as Phule wrote, “All the shudras belonged to the same fraternity” (Phule 2008: 19-20).

But as a sociological category and a political category, the term ‘Sudra’ can be extremely confusing. In the commonsensical understanding, Sudras are equated with the administrative category of Other Backward Classes ([OBCs] which includes categories like Most Backward Castes [MBCs]). This is still misleading as communities like the Saiva Vellalar Pillais of Tamil Nadu, who are technically Sudras, come under the general category. However, the OBCs form the bulk of the Sudras and ‘represent about half of the Indian population, but they have occupied a subaltern position so far’ (Jaffrelot 2000: 86). It is worth remembering that the administrative category of OBC was created after the consideration of several socio-economic factors of backwardness. Note that they are called ‘class’ while the ‘Scheduled Caste’ category has a clear mention of caste, and it covers castes that historically suffered and continue to suffer different forms of untouchability. The concreteness around the SC category facilitated the emergence of a pan-Indian Dalit identity and intellectual conversations, even if Dalit politics has been localised in practice and also hosts internal tensions. I have addressed some of the tensions within Dalit politics in Tamil Nadu in my earlier work (Manoharan 2019: 85). The vagueness and ambiguities around the Sudra-OBC-intermediate caste question results in not only their politics being localised, but also in the absence of pan-Indian intellectual debates on their identity/identities. One of the reasons for the paucity of such debates is the minimal representation of OBC academics in central universities in India, which is worse than the representation of academics from SC communities (Kumar 2018). Likewise, social scientist Yogendra Yadav claims that there is a reluctance to conduct a caste census as it may reveal ‘the very large numbers of the OBCs’ and also that their plight is ‘worse off than the top layer of the SC communities’ (Yadav 2021). Further explorations in this line might be very insightful to both empirical and theoretical studies on how caste as a system is exclusionary and oppressive not just to the Dalits but the OBCs as well.

In Tamil Nadu however, the situation for the OBCs has been better, to which Dravidian parties can take considerable credit. A recent work on Tamil Nadu’s political economy aptly titled The Dravidian Model: Interpreting the Political Economy of Tamil Nadu (Kalaiyarasan and Vijayabaskar 2021) explains that the populist policies pursued by the Dravidian parties that have been in power in the state brought about an inclusive model of development that led to significant socio-economic mobilities of the OBCs and SCs.

….to be continued in the next issue