Geetika Srivastava

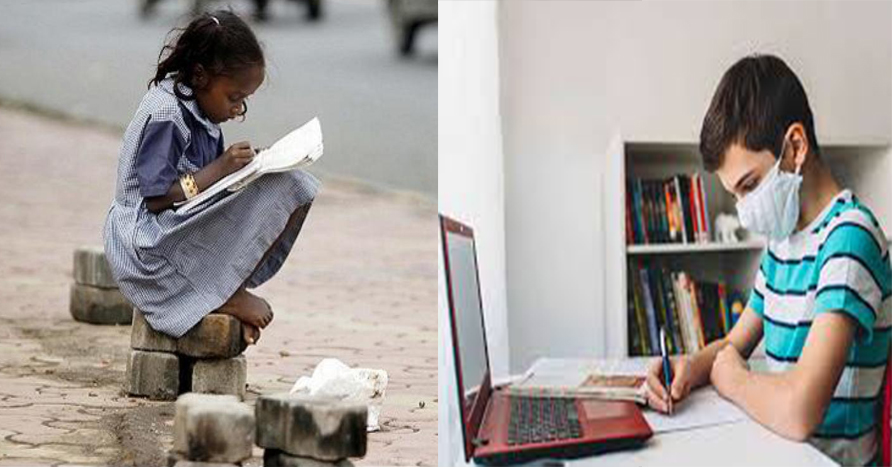

As the classroom is forced to shift online, a large segment of disadvantaged students is getting left behind

Every morning at 6, a soft aroma fills their one-room house in Malviya Nagar in Delhi as Sangeeta Kumari, 14, prepares tea for her parents. Her parents are sanitation workers and their day, which involves sweeping the city’s streets, is usually long.

In Gurugram, some 25 km away, Shruti Sinha, also 14, wakes up an hour after Sangeeta when her mother, a teacher, brings her a glass of warm milk and some biscuits.

Sangeeta and Shruti have several plans for their future. Both are ambitious. Both are students struggling with new modes of studies forced on them by the lockdown.

As the clock strikes 9, Shruti shuts herself up in her room with her laptop and smartphone, where she attends video lectures, back to back, till 11 am. Then, she is handed out worksheets for two different subjects, which has to complete and submit within the next two hours. After another online class and lunch, her private school ensures that students don’t miss out on extracurricular activities. So, some days, she attends an online exercise class, where her sports teachers demonstrate the moves for the students. Other days, she attends singing and art classes. She has also started online tuition for maths.

Digital school seems to have finally become a reality for his section of society. On the other hand, Sangeeta’s studies don’t start right away. Her family has one smartphone, the property of her parents. While they take it with them to work, she misses out on the daily one-hour video lecture that her government school organizes. Through the day, she takes care of her younger siblings, cooks meals, cleans the house and wash utensils.

Her time to learn begins when her parents return home. She can then finally access the assignments and audio clips that her teachers have sent via WhatsApp. “When I don’t understand something, I ask my land lord’s daughter,” she says.

Like Sangeeta, many of her classmates lack access to online education as they do not have smartphones, computers or internet connection. “There are about 16,00, 000 students in Delhi’s state government schools. About five per cent of them don’t have access to these facilities,” says P.D.Sharma,general secretary of the Government Schools’ Principals’ Association of Delhi. The figure indicates that about 80,000 students may not have access to online education in the country’s capital. So the situation in smaller cities and towns can only be imagined.

In some cases, individual teachers are trying to help through their own initiative. In Kolkata, for instance, Rumi (she wants only her first name to be used), a teacher at a government-run school, is exploring innovative ways to connect with her students.” I teach geography and there is always a need to have a visual component with the audio input,” she says. “We don’t have video conferencing as most students and their parents don’t know how to use apps that enable it.”

Rumi has 63 students in Class VI. Of these, many have returned to their villages and are often unreachable. She, however, tries to contact them once a week and gives them work that they can do it at home.

“I created a WhatsApp group with my students. Then I noticed that some of them had left the group. It turned out that they did not even know how they had managed to exit the group. Many of them were unable to use the application interface properly,” she says.

Rumi usually makes videos and sends them on a group. She also takes pictures of the atlas and maps to show the students what she is talking about. But the lack of experience in dealing with smartphones and the internet doesn’t plague the students alone. Oftentimes, teachers too have trouble sending large files to students, or shooting videos of their lectures.

According to a global survey by PEW, only 24 per cent Indians have access to smartphones. Not only does India lag among the list of emerging economies, there is also severe disparity in the ownership of smartphones between the genders: 34 per cent of men own smartphones as opposed to 15 per cent of women.

The situation is no better when it comes to internet connectivity.” Many of my students are unable to access notes, audio clips and so on because they don’t have enough money to recharge their data packs,” says Rumi. According to a National Statistical Office (NSO) survey, only 23.8 per cent households in the country have internet connectivity and only 10.7 per cent have access to computers.

So while students like Shruti are engaged e-learning via apps such as Zoom and Microsoft Teams, teachers and students such as Rumi and Sangeeta are struggling to get by with low-resolution cameras and WhatsApp audios. The divide isn’t only between the rich and the poor, it exists between genders and states and is also determined by several socio economic factors.

The mode of education, it seems, is thus insufficient. “I know that everything I’m teaching them now, I’ll have to teach again once school reopens,” says Rumi.

Some 30 children live in makeshift houses by an open sewage in Jangpura, New Delhi. Many of them are students enrolled in government-run schools. Most do not have smartphones. With no access to assignments, classes or homework, they are unable to study at all. “As the lockdown was imposed, we were unable to go and teach these children. Now with Unlock 1.0, we plan on organizing one-on-one teaching sessions with them,” says Nidhi Sharma, a member of the Robin Hood Army, a philanthropic organization that works on issues such as hunger and education.

“The problem is not just that we have no smart phones,” says Sona Lal (name changed on request), one of the Jangpura children who studies in Class XI.” When we went to school, there were teachers to look after us and make the younger children pay attention. Now, we are in a confined space where everyone is easily distracted. The younger ones just don’t study.”

Some of them had also been incentivized to go to school by the midday meals. Now, no cooked meals are provided, even though dry ration can be collected in the children’s name from the hunger relief centres set up by the State.

On its part, the government has brought about initiatives. Though programmes such as SWAYAM (Study Webs of Active- Learning for Young Aspiring Minds), it has been broadcasting various teaching courses to learners via Doordarshan and All India Radio – channels that may be accessible to a larger audience. It has also partnered with organisations such as the Central Square Foundation to make an e-repository of NCERT books, through a programme called Tic Tac Learn.

The Delhi government has also reportedly tied up with the Khan Academy for organizing online maths class for children. “Our plan was to provide tablets to all children to make e-learning more accessible. However, the pandemic distrupted this,” says Sharma of Delhi’s Principal’s Association. Talks to reopen school have already started, he adds.

The ground reality, however, continues to remain grim. As pandemic rages on and the lockdown extends, schools and colleges will be severely affected. No matter how many applications and programmes exist to assist children in learning. If they are only accessible to the upper tiers of society, there is a serious problem that needs urgent addressing.

The State, in 2020, promised every child aged 6 to 14 the Right to Education as a Fundamental Right. While the learning may have continued for some who have the ways and means to access education, for others, it seems it has come to a grinding halt. The inequality remains glaring.

Courtesy: Business Standard