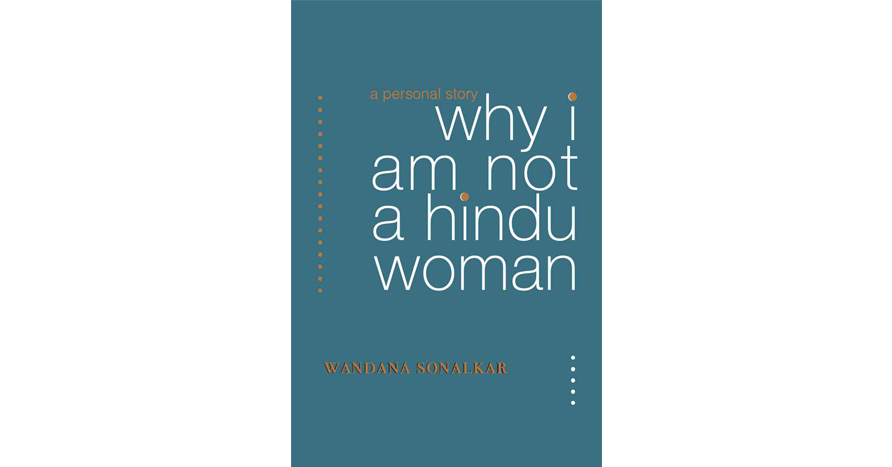

Why I am Not a Hindu Woman

– Wandana Sonalkar,

Women Unlimited

Rs. 350

G.Sampath

Drawing on lived experience, Wandana Sonalkar explains the concerns about Hinduism as it is practised today, including misogyny, caste and violence. Repudiation of a religion by a person born into it is a sub-genre by itself. Wandana Sonalkar’s Why I am Not a Hindu Woman invokes titles such as Bertrand Russell’s Why I am Not a Christian, Ibn Warraq’s Why I am Not a Muslim, and Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd’s Why I am Not a Hindu.

This book stands apart by virtue of being penned by a woman. This is significant not least because every major world religion discriminates against women. For Sonalkar, a retired professor of gender studies, the starting point of critique is her own life as a Hindu woman born in a family of Chandraseniya Kayastha Prabhus, a small community of ‘almost Brahmin’ upper castes. Reflecting on her formative years, she notes that her privileges — of caste, class, and location — may have helped her recover, but they did not protect her from the lacerations of growing up in a dysfunctional family whose dysfunction was rooted in brahminical patriarchy, also known as “Hinduism”.

Sonalkar was a little girl when her father starts an affair with a family friend. She writes, with devastating brevity, of the contrast in how the affair affected her mother, as opposed to the extended household. “My mother withdrew into even more lengthy puja rituals and more frequent fasts, eliciting outbursts of contemptuous anger from my father,” but “the extended Hindu family offered neither solace nor support… My father enjoyed the same respect and affection as always.”

Negation of equality

Comparing Hinduism to other religions, she finds it to be “inherently misogynist, where most religions are male-centred” and “as a religion, it does not believe in universal ethics or morality.” While some have argued that dharma is a universal Hindu ethic, she points out that it is “always determined by one’s social status and one’s gender… In Hinduism, dharma for the Brahmin is not the same as dharma for the Shudra.” It is partly thanks to this negation of equality at the core of Hinduism that a supremacist ideology such as Hindutva finds ready acceptance among so many Hindus, and “our liberal-democratic principles remain academic, they do not enter our hearts.”

If there is no universal belief system that defines a Hindu, then what makes one a Hindu? According to Sonalkar, “identification as a Hindu requires a performative act” such as visiting a temple or actions “that simultaneously announce one’s religion and one’s caste”. Hinduism does not have a singular belief system precisely because “Hindu identity is always a caste identity.”

Through the book, as Sonalkar switches between the personal and the political, she unravels the links between the violence of Hindutva and “the deep roots of violence in a caste-patriarchal Hindu social order”. Why does Hindu society tolerate violence against women, Dalits and Muslims, asks Sonalkar. She suggests that it is because of the different forms of ‘othering’ at work — the ‘othering’ of Hinduism’s internal inferiors (women and Dalits), and of the external enemy (Muslims). She contends that this dichotomy of interior/ exterior set against a common dynamic of ‘othering’ is the reason violence against Muslims is sought to be legitimised, while that against Dalits and women is sought to be invisibilised.

Insofar as anti-caste memoirs are over-populated by Dalit-Bahujans, this first-person account by a savarna intellectual is a welcome addition that has plenty to offer those seeking to understand the currents of divisiveness gaining ground in India.

Source: ‘The Hindu’