Any one who reads of the lawlessness of the Hindus in suppressing the movement of the untouchables, I am sure will be shocked. Why does the Hindu indulge in this lawlessness is a question he is sure to ask and none will say that such a question will not be a natural question and in the circumstances of the case a very pertinent question – Why should an untouchable be tyrannized if he wears clean clothes? How can it hurt a Hindu? Why should an untouchable be molested because he wants to put a tiled roof on his house?

How can it injure a Hindu? Why should an untouchable be presecuted because he is keen to send his children to school? How does a Hindu suffer thereby? Why should an untouchable be compelled to carry dead animals, eat carrion, and beg his food from door to door? Where is the loss to the Hindu if he gives these things up. Why should a Hindu object if an untouchable desires to change his religion? Why should his conversion annoy and upset a Hindu? Why should a Hindu feel outraged if an untouchable calls himself by a decent, respectable name? How can a good name taken by an untouchable adversely affect the Hindu? Why should the Hindu object if an untouchable builds his house facing the main road? How can he suffer thereby? Why should the Hindu object of the sound made by an untouchable falls upon his ears on certain days? It cannot deafen him. Why should a Hindu feel resentment if an untouchable enters a profession, obtains a position of authority, buys land, enters commerce, becomes economically independent and is counted among the well-to-do? Why should all Hindus whether officials or non-officials make common cause to suppress the untouchables? Why should all castes otherwise quarreling among themselves combine to make, in the name Hinduism, a conspiracy to hold the untouchables at bay?

To understand what is the Dharma for which the Hindu is ready to wage war on the untouchables, one must know the rules contained in the Smritis, particularly those contained in the Manu Smriti. Without some knowledge of these rules, it would not be possible to understand the reaction of the Hindus to the revolt of the untouchables.

All this of course sounds like a fiction. But one who has read the tales of Hindu tyranny recounted in the last chapter will know that beneath these questions there is the foundation of facts. The facts, of course, are stranger than fiction. But the strangest thing is that these deeds are done by Hindus who are ordinarily timid even to the point of being called cowards. The Hindus are ordinarily a very soft people. They have none of the turbulence or virulence of the Muslims. But, when so soft a people resort without shame and without remorse to pillage, loot, arson and violence on men, women and children, one is driven to believe that there must be a deeper compelling cause which maddens the Hindus on witnessing this revolt of the untouchables and leads them to resort to such lawlessness.

There must be some explanation for so strange, so inhuman a way of acting. What is it?

If you ask a Hindu, why he behaves in this savage manner, why he feels outraged by the efforts which the untouchables are making for a clean and respectable life, his answer will be a simple one. He will say: “What you call the reform by the untouchables is not a reform. It is an outrage on our Dharma”. If you ask him further where this Dharma of his is laid down, his answer will again be a very simple one. He will reply, “Our Dharma is contained in our Shastras”. A Hindu in suppressing what, in the view of an unbiased man, is a just revolt of the untouchables against a fundamentally wrong system by violence, pillage, arson, and loot, to a modern man appears to be acting quite irreligiously, or, to use the term familiar to the Hindus, he is practising Adharma. But the Hindu will never admit it. The Hindu believes that it is the untouchables who are breaking the Dharma and his acts of lawlessness which appear as Adharma are guided by his sacred duty to restore Dharma. This is an answer, the truthof which cannot be denied by those who are familiar with the psychology of the Hindus. But this raises a further question: What are these Dharma which the Shastras have prescribed and what rules of social relationship do they ordain?

The word Dharma is of Sanskrit origin. It is one of those Sanskrit words which defy all attempts at an exact definition. In ancient times the word was used in different senses although analogous in connotation. It would be interesting to see how the word Dharma passed through transitions of meaning. But this is hardly the place for it. It is sufficient to say that the word dharma soon acquired a definite meaning which leaves no doubt as to what it connotes. The word Dharma means the privileges, duties and obligations of a man, his standard of conduct as a member of the Hindu community, as a member do one of the castes, and as a person in a particular stage of life.

The principal sources of Dharma, it is agreed by all Hindus, are the Vedas, the Smritis and customs. Between the Vedas and Smritis, so far as Dharma is concerned, there is however this difference. The rules of Dharma, as we see them in their developed form, have undoubtedly their roots in the Vedas, and it is therefore justifiable to speak of the formal treaties on Dharma. They do not contain positive precepts (Vidhis) on matters of Dharma in a connected form. They contain only disconnected statements on certain topics concerned with Dharma. They contain enactments as to the Dharma. They form the law of the Dharma in the real sense of the term. Disputes as to what is Dharma and what is not Dharma (Adharma) can be decided only by reference to the text of the law as given in the Smritis. The Smritis form, therefore, the real source of what the Hindu calls Dharma, and, as they are the authority for deciding which is Dharma and which is not, the Smritis are called Dharmashastras (scriptures) which prescribe the rules of Dharma.

The number of Smritis which have come down from ancient times have been variously estimated. The lowest number is five and the highest a hundred. What is important to bear in mind is that all these Smritis are not equal in authority. Most of them are obscure. Only a few of them were thought to be authoritative enough for writers to write commentaries thereon. If one is to judge of the importance of a Smriti by the test as to whether or not it has become the subject matter of a commentary, then the Smiritis which can be called standard and authoritative will be the Manu Smriti, Yajnavalkya Smriti and the Narada Smriti. Of these Smritis the Manu Smriti stands supreme. It is pre-eminently the source of all Dharma.

To understand what is the Dharma for which the Hindu is ready to wage war on the untouchables, one must know the rules contained in the Smritis, particularly those contained in the Manu Smriti. Without some knowledge of these rules, it would not be possible to understand the reaction of the Hindus to the revolt of the untouchables. For our purpose it is not necessary to cover the whole field of Dharma in all its branches as laid down in the Smritis. It is enough to know that branch of the Dharma which in modern parlance is called the law of persons, or to put it in no-technical language, that part of the Dharma which deals with right, duty or capacity as based on status.

I therefore propose to reproduce below such texts from Manu Smriti as are necessary to give a complete idea of the social organization recognized by Manu and the rights and duties prescribed by him for the different classes comprised in his social system.

The social system as laid down by Manu has not been properly understood and it is therefore necessary to utter a word of caution against a possible misunderstanding. It is commonly said and as commonly believed that what Manu does is to prescribe a social system which goes by the name of Chaturvarna – a technical name for a social system in which all persons are divided into four distinct classes. Many are under the impressioon that this is all that the Dharma as laid down by Manu prescribes. This is a grievous error and if not corrected is sure to lead to a serious misunderstanding of what Manu has in fact prescribed and what is the social system he convicted to be the ideal system.

I think this is an entire misreading of Manu. It will be admitted that the divisions of society into four classes comprized within Chaturvarna is not primary with Manu. In a sense this division is secondary to Manu. To him it is merely an arrangement inter se between those who are included in the Chaturvarna. To many, the chief thing is not whether a man is a Brahman, Kshatriya, Vaishya or Shudra. That is a division which has existed before him. Manu added, accentuated and what did originate with Manu is a new division between (1) those who are within the pale of Chaturvana and (2) those who are outside the pale of Chaturvana. This new social division is original to Manu. This is his addition to the ancient Dharma of the Hindus. This division is fundamental to Manu because he was the first to introduce it and recognize it by the stamp of his authority.

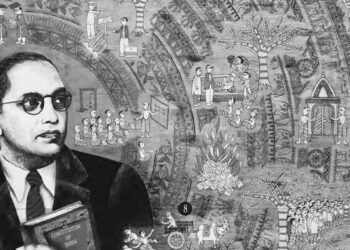

Courtesy: Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings and Speeches Volume V

published by the Government of Maharashtra.