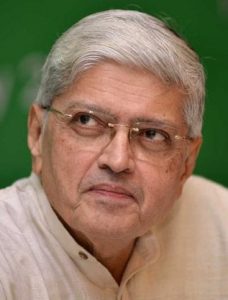

Gopalkrishna Gandhi

Former Governor of West Bengal and Translator of Tirukkural in English

He is beyond physical constructs to be appropriated; the saffron that has drifted to his image will not touch him

No one owns Tiruvalluvar.

He has left no dawdling trail of descendants saying, “Valluvar is ours”; no rival kin baying, ‘We, we, we not they are of his blood-line.” No clan, no caste claims can claim him. How can it? No one knows which home-row he was born into, lived in or — abandoned. He slips through the silken constrictions of descent and, equally, through the foam of faked bondings. The orthodox clothe him in the robes of sanctimony, radicals in the garbs of rebellion. To those who say in self-confidence that he was Vallabha, one must ask for evidence of that Brahminical status in his work. To those who claim he was Dalit, one must ask if anything he has written reflects that underprivileged status, whether with a sigh of acceptance or a howl of protest.

Valluvar is label elusive

The truth is Tiruvalluvar eludes labelling. The more mystifying he is, the more appealing he becomes. All we know of him is he wrote un-ageing thoughts that were un-striped by caste, un-coloured by class, un-scented by any denominational unguent. They were, simply, ideas, his ideas, stunning in their tight-bound form and un-tied, un-bound meaning.

Even as an ideator, in the zone of pure thought, Tiruvalluvar eludes capture, casking and commodification by idea-vendors. Those who publish, re-publish, translate, re-translate his 1,330 mind-rinsing couplets have their task lightened by their ready-to-print perfection form. His couplets come in the unvarying shape of four words in the first line and three in the second held together in a rhyme and metre format of repute. This form — exact, precise, taut — is a printer’s dream. But his thought is a publisher’s classification nightmare. Dealing with the ether of his thought is a difficult undertaking. They cannot classify their “forever-in-demand” product. Is it political verse, is it philosophy? Is it a manual for aspiring statesmen, is it a primer for pining lovers? Is it a speculation on life’s verities at their summit or at their plainest sameness? Naturalists are sold on the keenness of Valluvar’s eye in describing life in the wild. If the crocodile slouches in one couplet, the elephant galumphs in another while the heron waits, breath bated, to snap at unsuspecting prey. He is also unscientific at times; he is after all a fallible human being. He has unquestioningly accepted the popular belief that the owl is blinded by daylight. But his description of the behaviour of that commensal of man, the house crow is so sharp that the great ornithologist Salim Ali would have hailed him. The book can be said to fall, after all, under “natural sciences”.

Social scientists can be gripped by his word-pictures on customs, superstitions. Some of these he seems, dismayingly, to subscribe to. Contrastively, he seems to be on the side of transformative ideas presaging momentous changes in human mores. He glides through all these complications of human contriving to his nameless freedom.

The deft administrator in Rajagopalachari was so taken by Valluvar’s mastery of statecraft that he rendered it into a striking English version. But the moralist in him could not reconcile to the third book, the Book of Love (Kamathuppaal) . So much so that he draws a veil over its very existence. That is Rajaji. But lest anyone think Valluvar is a Tamizh Vatsyayana, forbear. Valluvar’s erotica is no lesson in pre-obstetric gynaecology. It is about love’s physicality, not the physiology of loving. Periyar, acknowledging with delight Valluvar’s extolling of that freedom, and yielding to none in admiration for the Tirukkural, takes its depiction of the compliant housewife head-on. That is Periyar.

The book’s sales are a global constant and a global amazement for his vendors do not, cannot, hold him to accept, contest either their products or their profits. He neither patents, nor is he patented. The Tirukkural lives, levitates above its reprints, beyond the unceasing flow of its nth edition, way away from the torrent of its citings, recitings.

Above religion

No religion holds him captive in its shrine or scripture. If a Hindu thinks he sees in a couplet here or a depiction there an image of Mahavishnu he should think again. Valluvar has declined to name or suggest the impress on him of any deity — male, female or in any of the celebrated transpositions of that pantheon — half-human and half-animal.

Jaina scholars have given highly estimable reasons for thinking Valluvar was in fact a Jaina master, Kundakundacharya by name. They maintain that when the Raj civilian F.W. Ellis translated the Kural’s Book of Virtue (Arathuppaal), he did so in the understanding that it was the work of a Jaina. But does Valluvar’s passionate denunciation of meat-eating and of the quaffing of spirits make him a member of that ascetic faith? Before putting one’s stamp of acceptance on that view, one must reflect on the fact that Valluvar starts the Kural with an invoking of the Creator and ends it with a celebration of Eros — neither of which sit well the tenets of the great Tirthankaras.

And as for the pious belief of the Reverend G.U. Pope, Valluvar’s famous English translator, that this likely resident of Chennai’s Mylapore’s seaside was deeply influenced by seaborne missionaries of the Sermon on the Mount, one can only smile. That diligent translator is also a devoted adherent of his Church and his Superiors.

Does this mean that agnostics or atheists can seat him at the head of their solemn conclaves of nay-saying? Attempts to read secular or “Adam-Eve” meanings into the work’s opening words — ‘Adi Bhagavan’ — are ideologically brave but one wishes they were textually persuasive as well.

We have sub-consciously aligned Tiruvalluvar’s imagined visage with that of a bearded sage, a Tamizh Vyasa, Visvamitra, Valmiki. Popular depictions of him have settled him in that countenance. But who can say with any empirical evidence that he did look like that? Maybe he did. But no one can affirm that with authority. Perhaps he resembled the Jaina muni that Ellis has immortalised in the gold coin that he caused to be minted, seated in a state of calm sans beard, sans beads and with a head-shield. Very worthily of him, Ellis does not give that figure a name. Valluvar’s images, painted or sculpted, are earnest examples of human reachings to one who is out of reach.

Appropriation of the totally un-affiliated is possible for they are right there, waiting to be snapped up by the heron of cultural possessiveness. Appropriation of the affiliated is also, incredibly enough, possible as long as the one being appropriated is dead and cannot scream in astonished disbelief.

Without boundaries

But Valluvar is in an altogether different category. You have to be a physical construct in order to be appropriated. Valluvar’s is an intangible intensity, an impalpable voltage, an indefinable actuality of ideas, depictions, advice, admonition, no one can pack into a bag to carry home. People can be appropriated, not ideas. Ideas can be countered. They cannot be co-opted.

No one can own Valluvar, I said. I must qualify that. Tamizh does, unequivocally, uniquely. But no one and nothing else. Does he own anything? He does — the idea of a family, for instance. His portrayal of the home-child is sui generis. Then, the idea of a nation. Valluvar’s portrait of a Good Nation is made of the tints of a Constitutional Preamble, no less. We may, on this 70th anniversary of our own, salute that Chapter.

The saffron that drifted to his image did not touch him. Like a wanton kite raised on a shallow wind, it wafted over his name to but waft out of it. Valluvar’s readers need not spend time thinking about the incident. Colours adhere to canvas, not to concepts. More people have been reminded — not that reminders were needed — of the master behind the Tirukkural as a result.

Tiruvalluvar has not had to endure the colouring. The colour has disappeared into the truths of the Tirukkural.

Courtesy: ‘The Hindu’