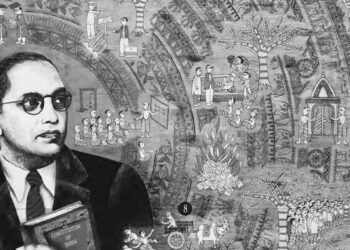

(The background of the provision for uniform civil code under Directive Principles of State Policy in Indian Constitution has been as follows at the time of debate and discussion on the subject in the Constitution Assembly. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar Chairman of the Drafting committee concluded the discussion on uniform civil code eventually Article 44 was included. The agenda behind uniform civil code of the BJP led National Democratic Front government at present is entirely different.)

ARTICLE 44

44. Uniform civil code for the citizens. –The State shall endeavour to secure for the citizens a uniform civil code throughout the territory of India.

ARTICLE 35 OF THE DRAFT CONSTITUTION

35. Uniform civil code for the citizens. –The State shall endeavour to secure for the citizens a uniform civil code throughout the territory of India.

CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY DEBATES

(Debated on 23 November 1948)

Mr. Vice-President: Now, we come to Article 35.

The Honourable Dr. B.R. Ambedkar: Sir, I have to request you to allow the Article to stand over for the present.

Mr. Vice-President: The Article is allowed to stand over the consideration later. Is it agreed to by the House?

Honourable Members: Yes.

…Mr. Mohamad Ismail Sahib (Madras: Muslim): Sir, I move that the following proviso be added to Article 35:

“Provided that any group, section or community of people shall not be abliged to give up its own personal law in case it has such a law.”

The right of a group or a community of people to follow and adhere to its own personal law is among the fundamental rights and this provision should really be made amongst the statutory and justiciable fundamental rights…

Now the right to follow personal law is part of the way of life of those people who are following such laws; it is part of their religion and part of their culture. If anything is done affecting the personal laws, it will be tantamount to interference with the way of life of those people who have been observing these laws for generations and ages. This secular State which we are trying to create should not do anything to interfere with the way of life and religion of the people.

Again this amendment does not seek to introduce any innovation or bring in a new set of laws for the people, but only wants the maintenance of the personal law already existing among certain sections of people. Now why do people want a uniform civil code, as in Article 35? Their idea evidently is to secure harmony through uniformity. But I maintain that for that purpose it is not necessary to regiment the civil law of the people including the personal law. Such regimentation will bring discontent and harmony will be affected. But if people are allowed to follow their own personal law there will be no discontent or dissatisfaction. Every section of the people, being free to follow it own personal law will not really come in conflict with others.Therefore, Sir, what I submit is that for creating and augmenting harmony in the laid it is not necessary to compel people to give up their personal law. I request the Honourable Mover to accept this amendment.

Mr. Naziruddin Ahmad: Sir, I beg to move:

“That to Article 35, the following proviso be added, namely:-

‘Provided that the personal law of any community which has been guaranteed by the statue shall not be changed except with the previous approval of the community ascertained in such manner as the Union Legislature may determine by law.”

In moving this, I do not wish to confine my remarks to the inconvenience felt by the Muslim community alone, I would put it on a much broader ground. In fact, each community, each religious community has certain religious laws, certain civil laws inseparably connected with religious beliefs and practices. I believe that in naming a uniform draft code these religious laws or semi-religious laws should be kept out of its ways. There are several reasons which underlie this amendment. One of them is that perhaps it clashes with Article 19 of the Draft Constitution.

In Article 19 it is provided that ‘subject to public order, morality and health and to the other provisions of this Part, all persons are equally entitled to freedom of conscience, and the right freely to profess, practise and propagate religion.’ In fact, this is so fundamental that the Drafting Committee has very rightly introduced this in this place. Then in clause (2) of the same Article it has been further provided by way of limitation of the right that ‘Nothing in this Article shall affect the operation of any existing law or preclude the state from making any law regulating or restricting any economic, financial, political or other secular activity which may be associated with religious practice’. I can quite see that they may be controlled.

But there are certain religious practices, certain religious laws with do not come within the exception in clause (2), viz. financial, political or other secular activity which may be associated with religious practices. Having guaranteed, and very rightly guaranteed the freedom of religious practice and the freedom to propagate religion, I think the present Article tries to undo what has been given in Article 19. I submit, Sir, that we must try to prevent this anomaly. In Article 19 we enacted a positive provision which is justiciable and which any subject of a State irrespective of his caste and community can take to a Court of law and seek enforcement. On the other hand, by the Article under reference we are giving the State some amount of latitude which may enable it to ignore the right conceded. And this right is not justiciable. It recommends to the State certain things and therefore it gives a right to the State. But then the subject has not been given any right under this provision. I submit that the present Article is likely to encourage the State to break the guarantees given in Article 19.

As I have already submitted, the goal should be towards a uniform civil code but it should be gradual and with the consent of the people concerned. I have therefore in my amendment suggested that religious laws relating to particular communities should not be affected except with their consent to be ascertained in such manner as parliament may decide by law. Parliament may well decide to ascertain the consent of the community through their representatives, and this could be secured by the representatives by their election speeches and pledges. In fact, this may be made an Article of faith in an election, and a vote on that could be regarded as consent. These are matters of detail. I have attempted by my amendment to leave it to the Central Legislature to decide how to ascertain this consent…

…Mahboob Ali Baig Sahib Bahadur: Sir, I move that the following proviso be added to Article 35:

“Provided that nothing in this Article shall affect the personal law of the citizen.”

My view of Article 35 is that the words “Civil Code” do not cover the strictly personal law of a citizen. The Civil Code covers laws of this kind: laws of property, transfer of property, law of contract, law of evidence etc. The law as observed by a particular religious community is not covered by Article 35. That is my view. Anyhow, in order to clarify the position that Article 35. That is my view. Anyhow, in order to clarify the position that Article 35 does not affect the personal Law of the citizen is also covered by the expression “Civil Code”. I wish to submit that they are overlooking the very important fact of the personal law being to much dear and near to certain religious communities. As far as the Mussalmans are concerned, their laws of succession, inheritance, marriage and divorce are completely dependent upon their religion.

Shri M. Ananthasayanam Ayyangar: It is a matter of contract.

Mahboob Ali Baig Sahib Bahadur: I know that Mr. Ananthasayanam Ayyangar has always very queer ideas about the laws of other communities. It is interpreted as a contract, while the marriage amongst the Hindus is a Samskara and that among Europeans it is a matter of status. I know that very well, but this contract is enjoined on the Mussalmans by the Quran and if it is not followed, a marriage is not legal marriage at all. For 1350 years this law has been practised by Muslims and recognised by all authorities in all states. If today Mr. Ananthasayanam Ayyangar is going to say that some other method of proving the marriage is going to be introduced, we refuse to abide by it because it is not according to our religion. It is not according to the code that is laid down for us for all times in his matter. Therefore, Sir, it is not a matter to be treated so depends entirely upon their religious tenets.

Source: India’s Constitution: Origins and Evolution published by Lexis Nexis, 2015.