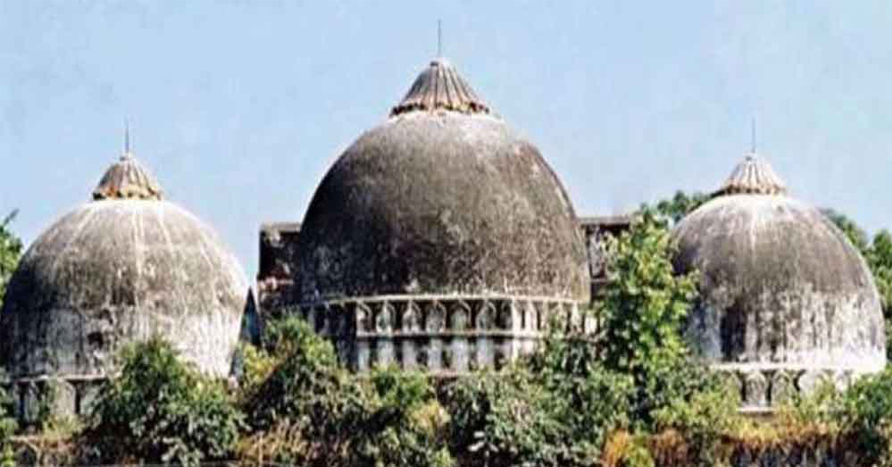

The Babri Masjid dispute reveals the dichotomy

between religious theory and practice

Devdutt Pattanaik

In Mecca, a large number of historic sites, including mosques, and even sites associated with Prophet Muhammad’s life, are being broken by the guardians of the Kaaba. This is being done to prevent these sites from becoming shrines, for that would amount to idolatry, which is forbidden in Islam. These structures and sites are being replaced by luxury hotels, a place for pilgrims to stay, a pragmatic solution that brings wealth to the land.

Why is such pragmatism not displayed when it comes to much less significant Islamic structure in India? Does the attachment of a section of Muslims to Babri Masjid lean towards idolatry? Or is it a fight for justice over a land dispute, and a case of land grabbing stretched over decades? Is the compensation not enough? Or is it a symbol of assertion of Muslim rights in a land where Muslims are a minority? Is it about faith, or land rights, or identity? Are the Hindus grabbing Muslim land? Or are Hindus simply reclaiming what they claim was always theirs, just like Jewish people reclaimed Israel after centuries of exile, displacing Palestinians who made that land their home during their long absence? And before Hindus, did the land belong to someone else? Or were Hindus the first migrants to the land?

Recent genetic studies have shown that everyone in India is a migrant. If we are all migrants, to whom then does any land belong? On what basis? Does it belong to those who came first, the mool-nivasis as some aboriginal tribal groups have now started identifying themselves? Does it belong to those who cultivated it first? Does it belong to those who worshipped the plants and rocks and ponds there, without cultivating it? Or to those who broke the rocks, filled the pond and cut the orchard to build a grand structure on it? Who decides? Judges?

Ways of claiming land

In ancient times, claim to land was established by burying the dead under homes and farms. In the Bible, what was identified eventually as the Promised Land is where Abraham buried his wife Sarah, and dug a well, and planted an orchard. Burial was a common practice in India too, until the Vedic Aryans proposed funeral ritual: burn the flesh and cast the bones into the waters. Do not be attached to body or land if you seek liberation from the cycle of birth and death, said the Vedic seers.

Vedic kings claimed land over which their royal horse travelled unchallenged. In other words, proprietorship was claimed by use of force. This was the ashwamedha yagna. In the Ramayana, rishis performed yagna to claim land using warriors to drive away rakshasas, who saw them as intruders. In the Mahabharata, forests were set alight, their residents burnt alive, to build settlements. Yet, the very same kings were told to let go of possessions and retire as ascetics to the forest before they died. For those who are attached to the world stay in the land of the living as ghosts, and do not make the journey to the land of ancestors, and thence to a new life.

When the Buddha died, it was ironical that the same students who had spent their entire lives listening to him speak about detachment ended up fighting over his bones. After much bickering, his remains were distributed amongst kings who built shrines over each relic. Buddhist teachers were also buried, their corpses anchored to earth, even in death, despite ‘blowing out the flame’ of identity.

This practice was mimicked by followers of many Hindu gurus. The students did not cremate the body of their teacher. The guru’s body was considered holy as the guru did not die; he simply slipped out of his mortal coil voluntarily at the appointed hour. And so the body had to be preserved, buried in salt, with a shrine above it, in the ashram. The body of the liberated soul was thus kept fettered for the benefit of the unliberated.

Many Muslims also have a similar practice. The holy man’s shrine becomes a focal point of worship, the dargah, where the burial site is venerated with flowers, cloth, incense, lamp and songs. This practice is common among Shia and Sufi Muslims, and is frowned upon by Sunni Muslims, who deem it idolatry.

In theory, Islam is anti-idolatry. But in practice, there is fetishisation of holy spots associated with saints and kings. Likewise, in theory, Hinduism, based on Vedanta, advocates detachment. But in practice, Hindus cling to mosques and dead bodies of holy men. For they mark land, establish property and grant power.

An assertion of faith

Babri Masjid is not just a land dispute as atheists and material philosophers would love to imagine. It is an assertion of faith: a tussle between some Muslims who see themselves as rightful owners of the land and some Hindus who see Muslims as migrants, invaders, foreigners. Those Hindus claim the land as their holy land, the place where god was born in mortal form. And those Muslims reject this claim, for they cannot recognise Ram as god, for to say so would be acknowledge another god beside Allah, and that is a sin, against the very first pillar of Islam. Some Hindus want to make Ram a historical entity, seeking to legitimise the site of his birth. But then to allow veneration of a historical entity is also idolatry in Islam. And it turns the temple into a memorial, a museum, not the way a temple is as per agama and tantra texts.

Before Allah, there shall be no false gods. No idols. However, Ram Lalla is all that. To accept the Supreme Court judgment is to accept the victory of idolaters. In theory, that is a problem. But plurality demands pragmatism. It demands accepting that mosques can be shifted, as they are in much of the Islamic world, as only idolaters see land as sacred. The faithful know that in Mecca, conscious effort is made not to turn sites linked to Muhammad’s birth and various events in his life into shrines. The various dargahs of South Asia are seen as idolatry to the puritanical Arab Wahhabi.

For peace, even Krishna asked the Pandavas to compromise — five villages instead of Indraprastha. But Duryodhana refused to give even a needlepoint of territory. In this regard, he is similar to Ravana, who would have his city burn, his people die, than let Sita go to her husband. This clinging to ‘mine’, hermits declared, was the symptom of ego.

If Islam is about rejecting all forms of idolatry, then Vedanta is all about detachment. To let go is a yogic virtue, says the Hindu guru. But that is theory, say Hindus, when it comes to Ayodhya or Kashmir. The ‘let go’ attitude, say the Hindutva warriors, is what got Muslims to wipe out Hindu civilisation in Pakistan and Bangladesh. For them, their fight for Ayodhya is essentially a fight of Hinduism’s survival in India. While Hindutva folks see this as real, non-Hindutva folks see this as paranoia.

Courtesy: ‘The Hindu‘