Satya Sagar | Journalist

In the ongoing movement against the Citizenship Amendment Act the images of Gandhi, Ambedkar and even Bhagat Singh have been put forward as symbols of religious tolerance, non-violence, Dalit empowerment and even socialist revolution.

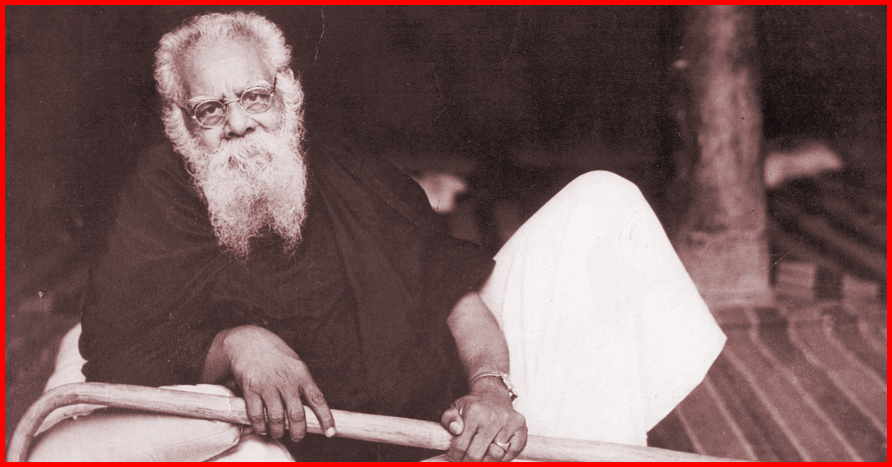

However, outside Tamil Nadu, few seem to have remembered E.V.Ramaswamy ‘Periyar’, the founder of the Dravidian movement– who perhaps offers the most potent challenge to the idea of a Hindu Rashtra — sought to be imposed by the BJP and its mentor RSS.

It is Periyar’s ideas, actions and most importantly his overall grammar of protest that, in my view, can most effectively take on the forces of Hindutva today. The Dravidian movement itself offers an excellent model to the rest of India to combat the barbarism of the caste system, redistribute resources, empower women and establish a society where reason and democracy prevail over the dictatorial urges of a tiny minority of upper caste Hindus.

Undoubtedly Periyar’s greatest cause was that of thoroughly exposing the Hindu caste system, which confers superior or inferior status to people by birth and not their individual merit. In other words, Hinduism does not have a conception of the human being as a universal entity with equal rights but divides society arbitrarily into the ‘high’ and the ‘low’.

“One should respect another in a way in which one expects to be respected by the other. This is a revolutionary principle for the Hindus. It can materialise not by reform but only by revolution. There are certain things that cannot be mended, but only ended. Brahmanic Hinduism is one such,” said Periyar. The key insight about Hindu society that Periyar highlighted was of it being an elaborate exploitative system — camouflaged with colourful mythology — that provided Brahmins and upper caste Hindus free labour, resources and monopoly over power.

The politics, administration and education system of Tamil Nadu at beginning of the twentieth century, like many other parts of India, was overwhelmingly dominated by Brahmins. For instance, although the Brahmins were only 3.2 per cent of the population, 70 per cent of the university graduates between 1870 and 1900 were Brahmins. This together with their control of all Hindu religious institutions and practice of untouchability against non-Brahmins led Periyar to dub the existing order as a ‘Brahminocracy’.

Periyar joined hands with other political thinkers to demand a blanket 50 per cent reservation for non-Brahmins in all government jobs and educational institutions. Despite strong opposition from the Brahmin lobby Madras state, the precursor to Tamil Nadu, was the first state to implement such reservations in 1928.

Next, Periyar sought to demolish the ‘varnashrama dharma’ of Hinduism by deconstructing its theoretical basis, which lay in Hindu scriptures like the Puranas and Hindu epics such as Ramayana and Mahabharata. Periyar and other scholars of the Dravidar Kazhagam he founded, laid bare the contradictions, immorality and biases of these religious texts in great detail and showed how they provided religious sanction to the caste system.

For example, the Dravidian movement offered a detailed critique of the Ramayana, which according to Periyar was essentially a tale of conquest by migrant Aryans coming from Persia and parts of central Asia of the original people of India, broadly categorized as Dravidians.

In their reading of the Ramayana the hero of the epic Rama is actually the invading villain and Ravana, the so-called ‘demon king’ is the hero, who is a victim of Rama’s colonial aggression (there is a clear and very heartening echo of this idea in the way the dynamic Dalit leader Chandrashekhar Azad has added ‘Ravan’ to his name).Periyar and his fellow activists also openly mocked the various gods of Hinduism for being as fallible as humans and still expecting to be worshipped without question (where was the Vishnu Chakra hiding when it was needed most against Ghazni or Clive?).

One of the keys to the success of the Dravidian movement was its brilliant use of pride in language and culture to awaken people, with many of its leaders being not just skilled orators but also good quality Tamil poets, musicians, actors and writers. Given the pride in the Tamil language that the Dravidian movement had aroused, it was not surprising at all that it strongly opposed the imposition of Hindi, with Periyar even conceiving the idea of a separate ‘Dravida Nadu’ in response.

The threat of separatism together with the fierce anti-Hindi agitation in Tamil Nadu encouraged other states around India to assert their rights and concerns, ultimately strengthening the principle of federalism and diluting concentration of power in New Delhi. It is this kind of positive and assertive sub-nationalism that is urgently needed today to defeat the fascist vision of a monolith and homogenizing ‘Hindu Rashtra’ — which is at its core is nothing more than a projection of power over India by Hindi speaking, upper caste Hindus.

On the social reform front, Periyar promoted what he called ‘Self Respect Marriages’, which enabled couples from any religion to get married in a secular manner through just a simple exchange of garlands and without the services of any Brahmin. Just imagine today if such marriages were to be conducted across India as part of the anti-CAA, NRC movement. (all the priests of cow belt India would start an armed revolt in response)

Periyar also repeatedly asserted the right of non-Brahmins to enter the sanctum sanctorum of Hindu temples, arguing that stopping them from doing so was to deny them status of human beings. In 1970 Tamil Nadu, again became the first state in India to have a legislation to ensure people from all castes could become temple priests if they wanted to.

Another area where Periyar was far ahead of his times was in his radical feminism, which he theorised well before the term itself was invented anywhere in the world. A big champion of widow marriage in his times, Periyar attacked the oppressive notion of female ‘chastity’ thus: “The tyranny of the male is the only reason for the absence of a separate word in our languages for describing the ‘chastity of men’.”

Of course, much water has flowed in the Kaveri since Periyar’s time and today Tamil Nadu’s ruling politicians have become notorious for rampant corruption, caste system and even forming alliances with the BJP, once seen as a hated promoter of ‘Aryan supremacy’ and Hindi chauvinism.

The State has also courted infamy in recent years for attacks on Dalits by the middle-castes who, while benefiting from the anti-Brahmin movement, do not want those further below them to assert their own rights. This was something Periyar had warned about, when he said that as long as there was a hierarchy of castes there could always be a ‘master-slave’ relationship between any of these.

Despite all this it can be said that the Dravidian movement effected the most successful social transformation in modern Indian history on the issues caste, education, assertion of language, federalism, social welfare and gender rights anywhere in the country.

It is not a coincidence at all that, compared to other parts of India, Tamil Nadu has the least amount of communal disturbances, with the Hindutva forces finding it extremely hard to grow here, despite many desperate attempts to do so. This is largely because Tamil Nadu, thanks to Periyar, is one of the few Indian states where the Brahmins no longer enjoy a hegemony over power or society and are unable to spread their centuries old philosophies of racism and hatred so easily.

To see Periyar as just the leader of the Tamils would be a grave mistake as his message was universal and relevant to the rest of India — especially in our times when a Brahminical theocracy is sought to be established under the garb of religious, majoritarian nationalism.