Devdutt Pattanaik

The earliest Hindu iconography showing a four-armed Vishnu has been found in Malhar in Madhya Pradesh, dating to 100 BCE

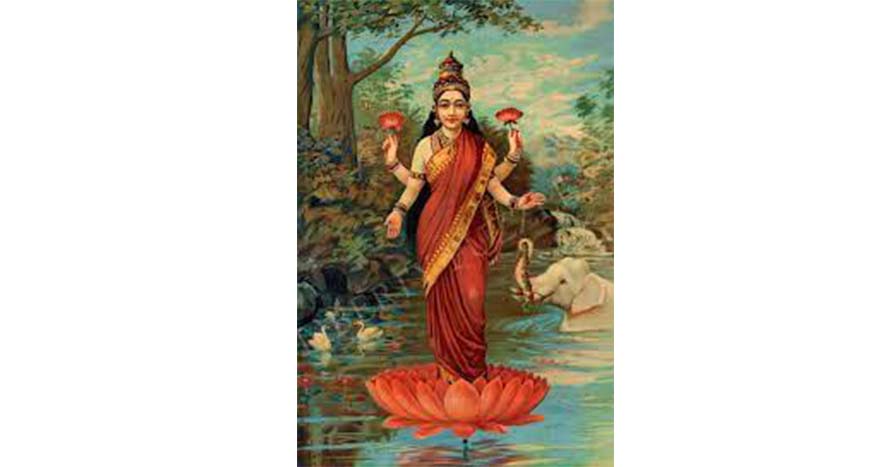

In Kushan coins, minted over 1,800 years ago, we come across images of a woman holding the horn of plenty. She is identified with the Roman Goddess Fortuna, the Greek goddess Tyche, the Central Asian Ardochsho, the Buddhist Hariti, and the Hindu goddess Lakshmi. Images of Lakshmi are also found on pillars and medallions of early Buddhist stupas. She is visualised there as a bejewelled woman, standing in a pond of lotus flowers, surrounded by elephants, very similar to Lakshmi images found in Hindu homes today. But there is one crucial difference. Lakshmi images today show her as four-armed, not two-armed.

The transformation of two-armed Lakshmi into four-armed Lakshmi happened in the Gupta period, 1,700 years ago, when the old Vedic way reinforced its power by redefining itself through the Puranas, and pushed back on Buddhist popularity. The shift began in the earlier Kushan period. The rise of four-armed deities effectively marks a turning point in assertive Hindu art.

Not more than two

The earliest Indian art comes from Harappa. Here we have images of men meditating, or escaping from tigers, or leaping on bulls, and women in procession, or resolving conflicts. All human characters have only two arms. Nearly 2,000 years after the Harappan period, we have the remarkably evolved Gandharan and Mathura art, mostly Buddhist, telling stories from the life of the Buddha and folktales inspired by Jataka tales. In Mathura art, we find the earliest image of Saraswati, from a Jain site, seated with a book in her hand. She too has two arms. Here we find celestial beings with wings, heads, and bodies of horses, indicating the clear influence of Greek and Persian art. But no four-armed beings.

The earliest images of Hindu gods are found on coins. Indo-Greek coins from 200 BCE have images of Krishna holding a wheel; he is two-armed. Kushan coins from 200 CE have images of Shiva holding a trident, many showing him with four arms. But the oldest Shiva lingam at Gudimallam, Andhra Pradesh, dated to 300 CE, shows Shiva with two arms only. From the Kushan period, we have the earliest images of Durga, showing her killing a buffalo. She too has multiple arms. The Kushans were migrants from South-West China and had no religious affiliations, which is why their coins in the western edge of their empire show Greco-Roman-Scyhtian influence while their coins in the eastern edge show Buddhist and Hindu influences. By the time of the Guptas, the Buddhist influence was on the wane.

The earliest Hindu iconography showing a four-armed Vishnu has been found in Malhar in Madhya Pradesh, dating to 100 BCE. It becomes more explicit in the Hindu temple in Deogarh that dates to the Gupta period, where we find the four-armed Vishnu in three forms: riding Garuda, reclining on Shesha, and as a teacher. When he is reclining, Lakshmi is at his feet. But she has only two arms.

The sprouting of multiple arms and later, multiple heads, differentiated supernatural beings from regular humans. In Buddhist art, Brahma and Indra are often shown bowing to the Buddha. How does one know they are not just any kings or priests? Brahma is shown with four arms, establishing his divine status and Hindu roots. In early Jain art, we find four images of the Tirthankara Rishabhdev facing four directions. But in Hindu art, we find chatur-mukha lingas showing Shiva’s head on four sides. In Jain art, we do find four-armed yakshas and yakshis, but the Tirthankara is never given supernatural form. At best, his limbs are longer than usual, reaching up to the knee, an indicator of being special.

No icons here

The idea of a god with multiple heads, arms and feet is first found in Vedic literature, and finds expression also in the Bhagavad Gita where Krishna takes his cosmic form, one that pervades every corner of the universe by expanding his form and by multiplying heads, arms, legs. The Vedic priests visualised the gods but did not turn them into icons of stone and metal. Local tribes gave form to their gods, but represented them symbolically through rocks, trees, rivers, or pots and baskets filled with food and water. Anthropomorphic images, where gods have human form, came much later. And images of gods with many heads and hands came even later. Tamil Sangam literature refers to gods like Mayon and Ceyon and Perumal, with their complexion, their abode, their banners, and sacred animals, but does not mention multiple arms.

Supernatural beings

The Mahayana and later the Tantrik schools introduced the idea of supernatural beings with multiple heads and arms into Buddhist art. But the form was associated with Bodhisattva, who is still to attain Buddhahood. He sprouts many heads and hands to see, hear and help the many suffering souls of the cosmos. On attaining Buddha status, he may have giant form, but retains only two arms.

Adi Shankaracharya is said to have established the worship of goddess Sharda, who is identified as Saraswati, nearly 12 centuries earlier. Early 20th century prints of the goddess show her as two-armed but new prints show her as four-armed. How do we resolve this mystery? Was she a Buddhist goddess who became Hindu under Shankara’s influence? Shankara was after all described by his opponents as Prachanna Buddha or crypto-Buddhist. And he did play a key role in eclipsing Buddhism from the Indian landscape. We will never know for sure.

But what we do know is that today, Hindu gods from Lakshmi to Ganesha to Saraswati are always depicted with four or more arms. They are two-armed only when they take mortal form, like Ram or Krishna. Four arms do what the halo did in Christian art — help the viewer quickly establish who is divine, who is supernatural, and who is worthy of veneration.

Source: ‘The Hindu’