*Jaikrishnan Nair

A century ago, Alummoottil Govindan Channar, an avarna (lower-caste person), was one of the few car owners in the erstwhile Travancore kingdom and also its biggest taxpayer. However, as an “untouchable” he was not allowed to drive past temples in his car. He had to get out and walk to the other side where his upper-caste driver would pick him up. Untouchability was so deep-rooted in Travancore and other parts of Kerala those days that Swami Vivekananda had once called the state a “lunatic asylum”.

That’s why the 1924 satyagraha against untouchability that started in Vaikom, a town 35km from Kochi and known as the ‘Varanasi of the South’, is regarded as a milestone in Kerala’s history. It eventually paved the way for the Temple Entry Proclamation of 1936 that granted members of the lower castes the right to worship in Hindu temples.

Launched with Gandhi’s support

On March 30, 1924, two untouchables – a Pulaya named Kunjappi and an Ezhava named Bahuleyan – along with Govinda Panikkar from the upper-caste Nair community, took the road around the Vaikom Shiva temple that was closed to the “polluting castes”. They were arrested and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment.

But they were acting on an idea that had arisen three years earlier in 1921 when social activist T K Madhavan had met MK Gandhi at Tirunelveli to seek his advice and support for launching an agitation for temple entry. Gandhi had approved of the agitation and suggested civil disobedience and non-violent satyagraha.

Gandhi’s involvement in the struggle proved crucial as it mobilised the educated upper-caste Hindu opinion in favour of temple entry. Madhavan wisely allied himself with the Congress’ larger movement, became a member and participated in the party’s Kakinada session in 1923 that made untouchability one of its main concerns and authorised the state Congress to take charge of the struggle.

Things moved quickly after that. The Congress’ Kerala wing formed an untouchability eradication council under K Kelappan that arrived in Vaikom on February 29, 1924 and decided to take out a procession through the prohibited roads on March 1. Following the intervention of local officials, the procession was postponed to March 30. However, it was changed to a satyagraha after the local administration banned the procession through a court order on March 13. Gandhi had already given permission for a satyagraha on March 3, 1924.

Struggle continued for months

The ashram of Sree Narayana Guru functioned as the camp for the satyagrahis. As the volunteers, including prominent leaders, tried to walk through the prohibited roads, they were arrested. None of them sought bail.

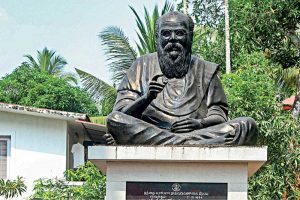

Support for the satyagraha poured in from different parts of the country. On April 13, social reformer and President of the Madras Congress Committee, E V Ramaswamy Naicker, popularly known as ‘Thanthai Periyar’, arrived at Vaikom. A group of 15 Akalis led by Lala Lal Singh and Kripal Singh opened a vegetarian mess for anyone who visited the ashram.

Later that year, when Kerala experienced one of its worst floods, volunteers stood neck-deep in water on the road leading to the temple. They took turns every three hours. This went on for around two months till the waters receded. The government then placed barricades and guards to prevent the entry of volunteers to the prohibited roads. The volunteers wanted to start a hunger strike but Gandhi didn’t allow it.

As the satyagraha started losing its public appeal, Gandhi arranged a peaceful jatha of Hindus from Vaikom to Thiruvananthapuram and back. They were to meet the Travancore maharani, who was also the regent at the time, and represent to her the need for revoking the ban on the freedom of movement. A memorandum signed by more than 25,000 upper-caste Hindus was submitted on November 13, 1924, to show that the upper castes weren’t against the opening of the roads. Although the government ignored it and sided with Hindu orthodoxy, the jatha helped raise social consciousness against untouchability.

Public opinion changed

As the government remained adamant, the volunteers became desperate. Some wanted to storm the prohibited roads. Gandhi grew concerned and arrived in Kerala on March 8, 1925, to hold discussions with all sides. He met the maharani, her minister, orthodox Hindus and local Congress leaders, and negotiated a settlement by which the government agreed to revoke the prohibitory orders and remove the barricades. In turn, the satyagrahis promised to respect the ‘teendal palaka’ (prohibitory signs) and not enter the prohibited roads.

Although the untouchables did not gain from this compromise, the satyagraha continued as a symbolic struggle for about eight more months. The public opinion created during this time forced the government to grant some concessions. The roads around the Vaikom temple, with the exception of two lanes leading to the eastern gopuram, were opened to all castes. Following this announcement, the satyagraha was called off on November 23, 1925.