Jared Diamond Writer, Awardee- 2016 Humanist of the year USA

Why human evolution and the multitude of extrasolar planets complicate the idea that we are special

Basic to religion is a presumed distinction between humans and so-called animals, and a presumed uniqueness of humans in the universe. But science is just our body of knowledge about the reality of the world as best we can understand it. So, what does science have to say about the foundations of religion in reality? Two areas of science are most relevant: one is evolutionary biology, which has been well understood for 157 years since Darwin’s publication of The Origin of Species; the other is astronomy.

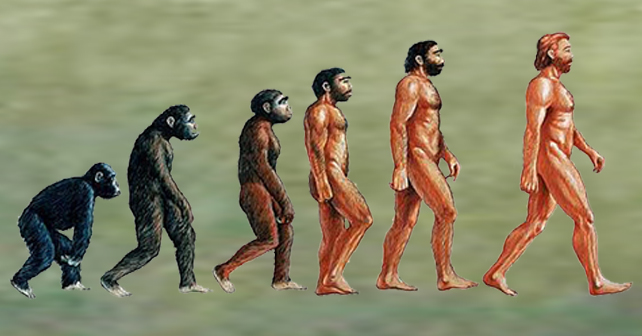

Let’s begin with evolutionary biology. Evolution is often mislabeled as a theory, but evolution of course is a well-established fact just as the earth’s revolution around the sun is not a theory but a well-established fact. We’ve had compelling evidence for more than a century that our modern human species gradually evolved from now-extinct species that anyone would agree were animals. So we can’t make a sharp distinction between humans and animals.

The human evolutionary line separated from the line leading to modern gorillas about seven million years ago, and then separated from the line leading to modern chimpanzees about six million years ago. Gradually, over the course of the last six or seven million years, various species of the human evolutionary line evolved to be more similar to us modern humans, and less dismissible as animals. But there was never a sharp break in time between humans and animals.

For most of this last six million years, there have been multiple co-existing human species, some more like us modern humans, and some more like so-called animals. It’s only in the last 32,000 years since the extinction of the Neanderthals that the human evolutionary line has consisted of only one species, namely us. There has also always been geographic variation within various human species, just as there is geographic variation within most animal species. Hence, at any given time during the emergence of modern Homo sapiens over the last 200,000 years, there were populations more like us moderns, and other populations less like us moderns and more like animals.

Also, we know that our species hybridized recently with at least two other human species now extinct, namely, with the Neanderthals and with Denisovans. Most of us today carry about 3 per cent of Neanderthal genes in our genome, but when our hybridization with Neanderthals was still taking place 32,000 years ago, there were first-generation hybrids who were 50 per cent Neanderthal in their genes, a second generation crossed with Neanderthals who were 75 per cent Neanderthal, and another second generation that crossed with Homo sapiens who were 25 per cent Neanderthal.

So, what do all these facts mean about religion’s supposed distinction between humans and animals? It means that there isn’t a clear distinction. There is variation in time. There is variation in space. But religions haven’t incorporated that fact. If there was a god that created humans in his or her or its image as distinct from animals, when and where did that god draw that arbitrary distinction between human and animals? Was it when we became just 25 per cent Neanderthal in our genes, or when we got down to 12 per cent, or 6 per cent, or now 3 per cent?

If we modern humans get judged and sent to heaven or hell, when and where in our evolutionary history did we start to get judged? Do chimpanzees get judged? Did Homo erectus get judged? Did 50 per cent and 25 per cent Neanderthals not get judged while 12 per cent Neanderthals did? Was it possible to have some kind of 50 per cent heaven reserved for 50 per cent Neanderthals? If a male chimpanzee today dies in the course of killing chimpanzees belonging to another chimpanzee clan, does that chimpanzee get rewarded by going to a heaven where he will be greeted by seventy virgin female chimpanzees?

I mention all these things as examples of the problems that the fact of biological evolution causes for a worldview based on a presumed sharp distinction between humans and animals. I’m not claiming that these basic problems are inseparable. But they are problems that need to be taken seriously for a religion, and as far as I know, they haven’t yet been taken seriously. That, then, is one of the two areas of science that I think has implications for religion.

The other area of science with consequences for religion is astronomy, specifically the subfield of astronomy concerned with so-called extrasolar planets, which are planets orbiting stars other than our sun. That issue of extrasolar planets is relevant to the supposed uniqueness of humans in the universe. Chimpanzees and primitive humans could already see with their naked eyes that there are thousands of stars up in the sky. Since Galileo invented the telescope, and as telescopes have been improved, we’ve learned that there are not thousands but trillions of trillions of stars.

But until recently, we couldn’t detect any planets orbiting those stars comparable to the nine or now eight planets that we know orbit our own star. We just didn’t have the methods. Because we’ve never been visited by flying saucers, it has seemed possible, although very improbable, to assume that the only intelligent life in the universe is we humans here on Earth (because, until recently, it’s always been the case that none of the other thirty million species on Earth rival us in intelligence).

In the past few decades, however, astronomers have developed a series of methods for detecting planets outside the solar system. As of May 10, 2016, astronomers had identified 3,264 planets outside our solar system, out of which 100 are the size of our planet Earth. Some nine of those planets lie in what is called the habitable zone of their stars, meaning that they lie at a distance from their star where it’s neither too cold, nor too hot, so life could evolve. Nine habitable planets. Out of the extrasolar planets we know of, 0.3 per cent may be habitable by life as we know it.

Most stars that we’ve searched have proved to have planets, so we have to assume that planets are the overwhelming rule, not the exception. If there are at least one trillion stars in the universe, and if most of them have planets, of which 0.3 per cent could support life as we know it, that means that there are about three billion planets capable of supporting life.

Experiments in laboratories suggest that it’s easy for a planet in the habitable zone to evolve life. The famous Miller Urey experiments of the 1950s showed that if you expose a container holding water, methane, ammonia, and hydrogen to either electricity or to ultraviolet light or to heat, then they will spontaneously form the building blocks of earth biology including amino acids, sugars, nucleotide bases, and porphyrins. So, it’s likely that the universe contains not just a billion planets capable of supporting life; it’s likely that the universe contains a billion planets actually supporting life.

Probably some of those planets have only living creatures less intelligent than us humans, and probably some of those planets have living creatures more intelligent than us humans. That makes it extremely unlikely that if there is a God, he, she, or it is more interested in us than in all the other more intelligent life forms that surely exist on other planets. This is another fact that needs to be taken seriously if one wants to reconcile religion with science.

Again, I’m not claiming that the facts of the real universe are incompatible with religion. It’s just to say that those facts of the real universe raise problems that have not yet been resolved. You may object to my conclusion that there are probably a billion planets out there supporting life. Why is it, you may ask, that we’ve not yet been visited by flying saucers and six-legged green creatures who demand to be taken to our leader? Doesn’t this suggest that there really are not inhabited planets with life out there? No. The reason we haven’t been visited by flying saucers is pretty clear, if we consider the space-distance problem, the target problem, and the civilization lifetime problem.

As for the space-distance problem, the speed of light (186,000 miles per second) is the maximum speed you can achieve in the universe. But even if a flying saucer could achieve the speed of light, the closest stars to Earth are several light-years away, which means that a flying saucer going at top speed is still going to take several years to reach the earth. But it’s extremely unlikely that a flying saucer is going to approach the speed of light. It’s going to take a prohibitively long time to reach us. That makes it implausible that we are going to see flying saucers.

The second reason we haven’t encountered flying saucers is the target problem. Given that there are billions of stars out there, it means that from any planet capable of launching a flying saucer, there are also large numbers of potential targets, many far closer than Earth. Earth is really just one of an enormous number of targets for any civilization capable of sending out flying saucers. That’s another reason that we’ve not yet been visited.

The third reason concerns the likely duration of a civilization capable of sending out flying saucers. Just consider the history of life on Earth. After four-and-a-half billion years, we finally get an intelligent species, by our standards, and in 1957, we finally launch Sputnik, which doesn’t escape from the solar system but at least it’s up there in space. And a few decades later we launch an object that is headed off into space. But given the rate at which we’re destroying the basis of our own foundations, sometime be-fore the year 2050 human civilization will have destroyed its capacity for sending objects into outer space, which means that of the four-and-a-half billion years of life on Earth, there will have been only a couple of decades available for sending objects out into the galaxy. We have to assume, based on our experience and common sense, that any civilization capable of sending out flying saucers will also have developed the capacity to destroy itself. These are, I’m sure, the three reasons why we have not yet been visited by a flying saucer, nor will we be.

Courtesy : November / December 2016

‘The Humanist’