The term ‘Centre’ is absent in the Constitution as the Constituent Assembly did not want to centralise power

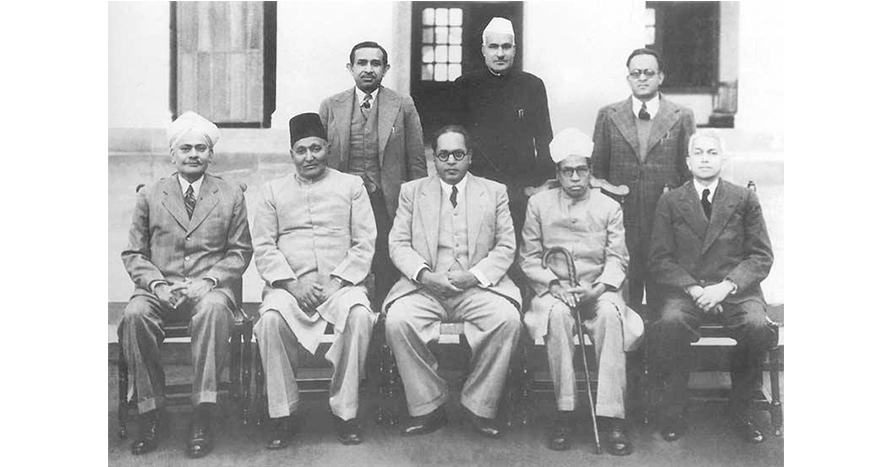

Members of the Constitution Drafting Committee in February 1948; (Sitting, from left) N. Madhava Rao; Saiyid Muhammad Saadulla; Dr. B.R. Ambedkar; Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar and Sir B.N. Rao. (Standing from left) S.N. Mukerjee, Jugal Kishore Khanna and Kewal Krishan. Photo Credit: The Hindu Photo Archives

Mukund P. Unny

The Tamil Nadu government’s decision to shun the usage of the term ‘Central government’ in its official communications and replace it with ‘Union government’ is a major step towards regaining the consciousness of our Constitution. Seventy-one years since we adopted the Constitution, it is time we regained the original intent of our founding fathers beautifully etched in the parchment as Article 1: “India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States”. If a student of Indian polity attempts to trace the origin of the term ‘Central government’, the Constitution will disappoint him, for the Constituent Assembly did not use the term ‘Centre’ or ‘Central government’ in all of its 395 Articles in 22 Parts and eight Schedules in the original Constitution. What we have are the ‘Union’ and the ‘States’ with the executive powers of the Union wielded by the President acting on the aid and advice of the Council of Ministers headed by the Prime Minister. Then, why did the courts, the media and even the States refer to the Union government as the ‘Centre’?

Even though we have no reference to the ‘Central government’ in the Constitution, the General Clauses Act, 1897 gives a definition for it. The ‘Central government’ for all practical purposes is the President after the commencement of the Constitution. Therefore, the real question is whether such definition for ‘Central government’ is constitutional as the Constitution itself does not approve of centralising power.

Intent of Constituent Assembly

On December 13, 1946, Jawaharlal Nehru introduced the aims and objects of the Assembly by resolving that India shall be a Union of territories willing to join the “Independent Sovereign Republic”. The emphasis was on the consolidation and confluence of various provinces and territories to form a strong united country.

Many members of the Constituent Assembly were of the opinion that the principles of the British Cabinet Mission Plan (1946) be adopted, which contemplated a Central government with very limited powers whereas the provinces had substantial autonomy. The Partition and the violence of 1947 in Kashmir forced the Constituent Assembly to revise its approach and it resolved in favour of a strong Centre. The possibility of the secession of States from the Union weighed on the minds of the drafters of the Constitution and ensured that the Indian Union is “indestructible”. In the Constituent Assembly, B.R Ambedkar, the Chairman of the Drafting Committee, observed that the word ‘Union’ was advisedly used in order to negative the right of secession of States by emphasising, after all, that “India shall be a Union of States”. Ambedkar justified the usage of ‘Union of States’ saying that the Drafting Committee wanted to make it clear that though India was to be a federation, it was not the result of an agreement and that therefore, no State has the right to secede from it. “The federation is a Union because it is indestructible,” Ambedkar said.

The usage of ‘Union of States’ by Ambedkar was not approved by all and faced criticisms from Maulana Hasrat Mohani who argued that Ambedkar was changing the very nature of the Constitution. Mohani made a fiery speech in the Assembly on September 18, 1949 where he vehemently contended that the usage of the words ‘Union of States’ would obscure the word ‘Republic’. Mohani went to the extent of saying that Ambedkar wanted the ‘Union’ to be “something like the Union proposed by Prince Bismarck in Germany, and after him adopted by Kaiser William and after him by Adolf Hitler”. Mohani continued, “He (Ambedkar) wants all the States to come under one rule and that is what we call Notification of the Constitution. I think Dr. Ambedkar is also of that view, and he wants to have that kind of Union. He wants to bring all the units, the provinces and the groups of States, everything under the thumb of the Centre.” However, Ambedkar clarified that “the Union is not a league of States, united in a loose relationship; nor are the States the agencies of the Union, deriving powers from it. Both the Union and the States are created by the Constitution, both derive their respective authority from the Constitution. The one is not subordinate to the other in its own field… the authority of one is coordinate with that of the other”.

The sharing of powers between the Union and the States is not restricted to the executive organ of the government. The judiciary is designed in the Constitution to ensure that the Supreme Court, the tallest court in the country, has no superintendence over the High Courts. Though the Supreme Court has appellate jurisdiction — not only over High Courts but also over other courts and tribunals — they are not declared to be subordinate to it. In fact, the High Courts have wider powers to issue prerogative writs despite having the power of superintendence over the district and subordinate courts. Parliament and Assemblies identify their boundaries and are circumspect to not cross their boundaries when it comes to the subject matter on which laws are made. However, the Union Parliament will prevail if there is a conflict.

Word play

The members of the Constituent Assembly were very cautious of not using the word ‘Centre’ or ‘Central government’ in the Constitution as they intended to keep away the tendency of centralising of powers in one unit. The ‘Union government’ or the ‘Government of India’ has a unifying effect as the message sought to be given is that the government is of all. Even though the federal nature of the Constitution is its basic feature and cannot be altered, what remains to be seen is whether the actors wielding power intend to protect the federal feature of our Constitution. As Nani Palkhivala famously said, “The only satisfactory and lasting solution of the vexed problem is to be found not in the statute-book but in the conscience of men in power”.

Source: ‘The Hindu’